Library of Congress

Nestled in the hills of Albermarle County, Virginia, lies Thomas Jefferson’s “Monticello.” Constructed with the neoclassical architectural principles of the Italian Renaissance, the home of the United States’ third president now stands as a testament to the cultural values and aesthetics of the Early Republic that he championed. The main building’s octagonal dome and pedimented windows harkened back to a classical, European tradition. The World Heritage Site and National Historic Landmark also boasts technological innovations, like dumbwaiters, that are evidence of a streamlined practicality that was uniquely American. The outbuildings surrounding Jefferson’s home and gardens are stark reminders that the beautiful villa was built and operated by enslaved labor.

For Jefferson, the arts held immense power—they could please the eye, educate the public, promote enlightened ideals, and even reflect the aspirations of a new nation. As the United States matured, its citizens have erected buildings, established cultural institutions, and created works of art that reflect their evolving beliefs and changing environments. Many of these cultural expressions have survived and serve as important reminders of the diverse beliefs and values that shaped the United States as we know it today.

Wikimedia user "Yvphotos"

Social institutions allow Americans to shape their communities to reflect their values. Since the dawn of the Progressive Era, reform movements have allowed groups to work collectively to fight social injustice and improve the lives of people across the nation. During the settlement house movement of the late 1800s, many social reformers believed that poverty, immorality, and inequality could be eradicated from American society through institutions that provided education and strict moral guidance. One of the most prominent examples of these “settlement houses” was Jane Addams’ Hull House. Here, Chicago’s newly arrived European immigrants could take English language and home economics courses, and participate in various social and educational programs. In the United States’ major cities, recreational organization like the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) provided healthy, recreational activities inspired by Christian principles for single men living away from home. Where these organizations sought institutional reforms to combat social ills, others found spiritual solutions for worldly problems.

Historic American Building Survey/Library of Congress

Religious movements have also profoundly shaped the United States’ cultural landscape throughout its history. During the Second Great Awakening—a Protestant revival movement during the early 1800s—Americans responded to a rapidly industrialized and increasingly secular society by turning to new spiritual practices. Millenialist groups—religious groups who believed that the Second Coming of Jesus Christ was imminent—introduced new understandings about worship, marriage, and family. Many of their practices challenged early America’s social and economic order. The Shakers established nineteen communitarian villages from Maine to Kentucky where they practiced pacifism, gender equality, and celibacy. The Oneida Community in upstate New York practiced “complex marriage” and “Bible Communism.” After the murder of their prophet Joseph Smith in 1844, the Latter-day Saints fled violence and religious persecution for their practice of polygamy or “plural marriage.” Thousands of “Mormons” travelled west and eventually settled in Utah territory. They built thriving centers of commerce and religious life in Salt Lake City and other towns throughout the intermountain west. These are just a few of the American religious groups that have harnessed the power of faith to reshape the world around them.

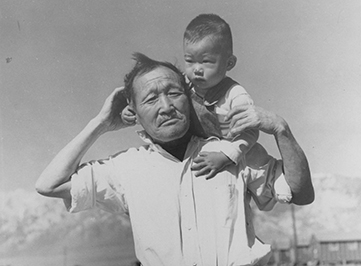

Throughout its history, Americans have also established religious institutions to uplift their communities and sustain cultural ties. Like many groups facing religious persecution, Jews fleeing Spain and Portugal during the Inquisition looked to rebuild their lives in the “New World.” A number of these emigres formed a Jewish congregation in Rhode Island during the 1600s. Their descendants built the Touro Synagogue, the oldest synagogue in the United States. Since its dedication in 1763, it has served as a center for Jewish community life and a symbol of religious freedom for all Americans. Later, during the late 1800s, Sioux Indians’ practiced the spiritual “Ghost Dance” in the hopes of warding off white settlers encroaching on their lands.The dance so frightened white settlers that tensions between the two groups escalated into a series of battles in the Dakotas, the most well-known of them being the Wounded Knee Massacre (1890). During World War II, Buddhist, Shinto, and Christian churches were important resources for Japanese Americans seeking to preserve Japanese culture and survive persecution. They served as places of worship, hosted youth organizations and Japanese language schools, and even stored the furniture and valuables for Japanese families forcibly relocated into internment camps during the war.

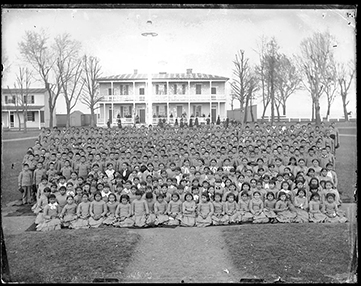

National Anthropological Archives

While social reform movements seek to improve the moral health of a community and religious movements work to improve spiritual health, education movements operate with the belief that an informed citizenry is essential to the civic health of the American republic. Education—from the free, uncensored exchange of ideas, to the artisan apprenticeship traditions, to the establishment of schools and universities—has played an important role in personal self-improvement, community uplift, and even cultural assimilation. During the late nineteenth century, self-made millionaires believed that that access to learning is the key to success in America. Gilded Age industrialists like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller donated millions of dollars to building schools and libraries, opened universities, and established institutes for international peace and medical research. For example, in the early 1900s, steel tycoon Carnegie donated nearly $5 million to the New York Public Library. His hope was that average workers could improve themselves with unrestricted access to books.

But the dream of free access to education proves difficult to achieve for marginalized peoples throughout American history. In southern states before the Civil War, it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read or write. During Reconstruction, emancipated black Americans established institutions that solidified community ties, including churches, schools, and institutes for vocational training. These were sources of empowerment and healing during periods of racist violence. African Americans continued to fight for equal access to education after Reconstruction failed and decades of organizing culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which ended legal segregation in public schools and the “separate but equal” era.

Education can be used as a powerful tool for cultural assimilation and there are examples of this in American history. Federal policies of the 1800s forcibly relocated indigenous peoples onto reservations in order to free up western territories for white settlers. In order to “civilize” younger generations, U.S. officials removed Native American children from their homes and enrolled them in American boarding schools where they were given “Christian” names, dressed in European-style clothing, and taught the English language. This practice continued into the twentieth century. Many of these children were forbidden to speak their native language and participate in traditional ceremonies. For many indigenous tribes, forced “Americanization” in schools contributed to the loss of their native language, oral histories, and cultural autonomy.

NPS

The performance and visual arts of Americans also play important social, cultural, and even political roles in everyday life. Stage plays, novels, dances, and paintings were not just sources of beauty and entertainment for mass audiences; they also serve as tools for community building and social education. Folk music and other artistic traditions comforted and bonded stranger-immigrants in the New World, whether they came voluntarily from Europe or were captives of the slave trade. Nineteenth century abolitionists wrote novels about slavery to win support for emancipation, the most notable one being Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Following World War I, African American artists, writers, musicians, and scholars flocked to New York City’s Harlem. During the Harlem Renaissance, the work of African Americans like Langston Hughes, Lois Mailou Jones, Josephine Baker, and Paul Robeson pulled from European, African, and Afro-Caribbean artistic styles to develop new genres that explored the complexities of African American identity and confront racism in U.S. society. As a documentary photographer for the Farm Security Administration and the War Relocation Authority, Dorothea Lange managed to capture the tragedies of Depression-Era poverty and the resilience of everyday Americans in the face of discrimination and adversity.

If—according to some Americans—art was meant to please and reflect the ideals and morals of greater society, then artistic expression that seemed to deviate from social norms was often perceived as a threat to society’s moral fabric. At the height of anticommunism during the 1950s, conservative politicians and select members of the U.S. entertainment industry joined forces to blacklist actors, writers, and directors with alleged Communist ties or who simply expressed progressive political beliefs. In 1947, ten writers and directors appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee and were cited for contempt of Congress after refusing to “name names.” Many others besides the “Hollywood Ten” were denied employment, had studio contracts revoked, and had their professional reputations irreparably damaged by the Hollywood Blacklist. Artistic censorship did not end with the Cold War. While the First Amendment protects an artist’s right to freely express themselves in their artwork, regardless of its content or subject matter, disputes often arise when artists create controversial artwork with public funding. During the culture wars of the 1980s and 90s, artists that received federally funded grants and prizes like Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe had their work censured and pulled from displays.

Arts, culture, and education are among the many ways that people interact with their environment and respond to the world around them. Whether they are establishing educational institutions, erecting houses of worship, or molding sculptures out of marble and clay, people leave behind testaments to their personal values and national identity. Americans are no exception. As our nation’s leading keeper of Americans’ stories, the National Park Service preserves the cultural expressions that mark our country’s landscape and interprets what they reveal about the world we inhabit.

Visit the National Park Service Telling All Americans' Stories portal to learn more about American heritage themes and histories.

Last updated: July 27, 2021