Last updated: August 8, 2025

Article

Bonus Expeditionary Forces March on Washington

"If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America."

-Washington Daily News

Library of Congress (LC-DIG-hec-36887)

Hard times prompt veterans to seek promised bonus early

In the years after World War I, a long battle over providing a bonus payment to WWI veterans raged between Congress and the White House. Presidents Harding and Coolidge both vetoed early attempts to provide a bonus to WWI veterans. Congress overrode Coolidge’s veto in 1926, passing the World War Adjusted Compensation Act, otherwise known as the Bonus Act.The act promised WWI veterans a bonus based on length of service between April 5, 1917 and July 1, 1919; $1 per day stateside and $1.25 per day overseas, with the payout capped at $500 for stateside veterans and $625* for overseas veterans. The catch was this bonus would not pay out until each veteran’s birthday in 1945, paying out to his estate if he should die before then. Although veterans were allowed to borrow against the bonus certificate beginning in 1927, by 1932, banks were short on credit to give.

Protesters gather in Washington

In May 1932, jobless WWI veterans organized a group called the “Bonus Expeditionary Forces” (BEF) to march on Washington, DC. Suffering and desperate, the BEF’s goal was to get the bonus payment now, when they really needed the money. Led by Walter W. Walters, the veterans set up camps and occupied buildings in various locations in Washington, DC. The largest camp was a shantytown on the Anacostia Flats, across the river from Washington’s Navy Yard.By summer, at least 20,000 people had joined the camps, with some estimates putting the total number above 40,000. Many were joined by their families. But the camps attracted an undesirable element as well. President Hoover later claimed “the march was largely organized and promoted by the Communists, and included a large number of hoodlums and ex-convicts bent on raising a public disturbance.” Using scrap wood and other salvaged materials, the protesters constructed a vast field of shacks in view of the Capitol dome, prepared for a siege of Congress.

Library of Congress (LC-DIG-hec-36890)

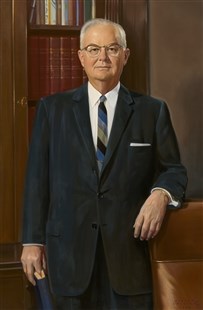

Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives

Bill introduced to offer relief to WWI veterans

Taking up the veterans’ cause, Congressman Wright Patman (D-TX) - himself a WWI veteran - sponsored a bill that would immediately provide a $2.4 billion bonus payment to WWI veterans. During the debate over the bill on June 15, 1932, Congressman Edward Eslick (D-TN) was making an address on the floor of the House of Representatives when he suffered a heart attack and died. The House carried on with its business, though, and with hundreds of veterans cheering from the gallery, the House passed the bill that same day.Republicans opposed the Patman bill mainly because it required the government to spend money it did not have in the treasury. The government was no exception to the hard times that had befallen the nation. Although the bill had passed in the House, the bill did not have the votes to pass in the Senate. The Senate voted down the bill on June 17. No immediate relief would be coming to the veterans. Even if the bill had passed the Senate, it most likely would have been vetoed by President Hoover, just as the bonus itself had been vetoed by Coolidge and Harding in the preceding years.

The bill had come to a vote and failed, but many in the Bonus Expeditionary Force refused to pack up and go home. Instead, they continued their occupation of the Anacostia Flats and vacant buildings in the District of Columbia into July.

Violence breaks out

On July 28, Attorney General William Mitchell ordered the DC police to remove the protesters from government property. At the time, about 50 protesters occupied buildings along Pennsylvania Avenue. When police arrived to move them out, a riot erupted, and police shot and killed two protesters. After that, the Army was called in to restore order.

National Archives, ARC identifier 593253

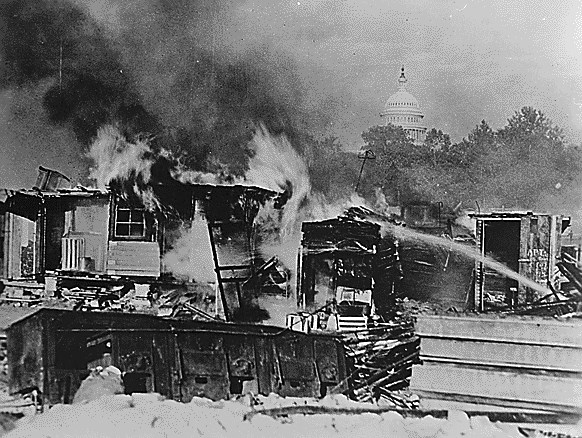

Hoover twice sent messages to MacArthur to not cross the bridge, but MacArthur ignored them and continued pressing into the BEF camp on the Anacostia Flats on the far side of the river. The camp was still inhabited by about 10,000 people, who were driven off by the cavalry with tanks and tear gas. The infantry followed, setting fire to the shanties. The wounded overwhelmed DC’s hospitals.

The Army viewed the operation as a success: the Bonus Expeditionary Forces had been dispersed permanently. The press overwhelmingly disagreed.

The Washington Daily News, typically sympathetic to Hoover’s Republicans called it “A pitiful spectacle,” to see “the mightiest government in the world chasing unarmed men, women, and children with Army tanks. If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America.”

National Archives, identifier 531102

Political fallout

1932 was an election year, and the economy was the prevailing issue. The “pitiful spectacle” of starving, ragged veterans being driven off by tanks weakened Hoover’s bid for re-election. In November, his opponent, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was swept into office by an American populace eager for change. Roosevelt became America’s longest-serving president, elected to four terms in office. Another Republican would not hold the White House until Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration in 1953 — his immense popularity for his leadership in World War II vastly overshadowing his role in the affair on the Anacostia Flats.

NPS / Nathan King

Visiting the Anacostia Flats

Today, the Bonus Expeditionary Forces and the drama of 1932 are largely forgotten, but you can still visit the same field where the shantytown briefly stood. Now playing fields host flag football and soccer. Picnickers enjoy summer afternoons along the river. Residents walk, jog, and bike the Anacostia River Trail. And the land is home to the US Park Police and National Capital Parks - East headquarters.*$625 in 1926 equates to roughly $8,600 in 2016 dollars. Distributed among 4.7 million veterans, the total payout would have been about $2.4 billion in 1926, equating to roughly $33 billion in 2016 dollars.