Part of a series of articles titled On Their Shoulders: The Radical Stories of Women's Fight for the Vote.

Article

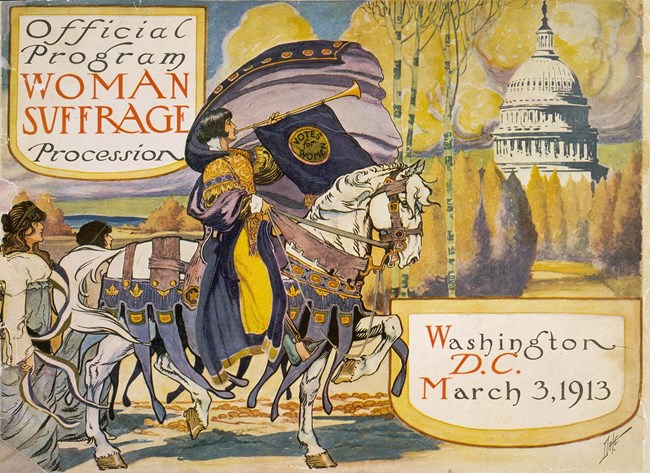

The Great Suffrage Parade of 1913

By Rebecca Boggs Roberts

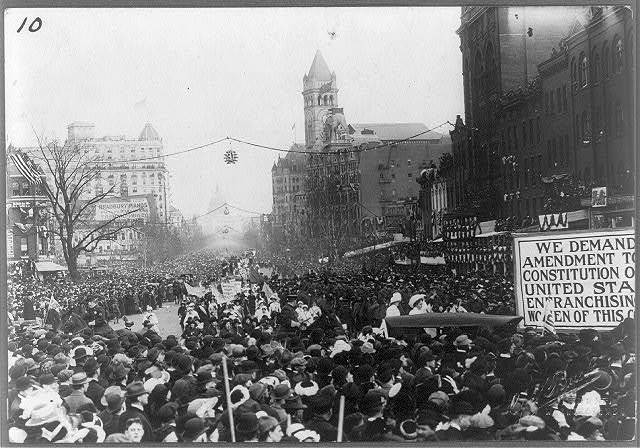

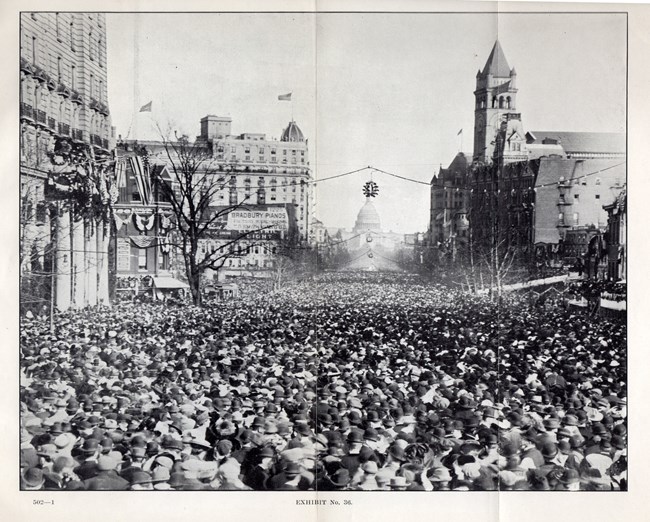

On the afternoon of March 3, 1913, the day before the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson as the nation’s 28th president, thousands of suffragists gathered near the Garfield monument in front of the U.S. Capitol. Grand Marshal Jane Burleson stood ready to lead them out into Pennsylvania Avenue at exactly 3:00, in what became the first civil rights march on Washington, DC. It also proved to be turning point in the fight for the vote. By the early twentieth-century, over 50 years after Seneca Falls, suffragist Harriot Stanton Blatch said the cause “bored its adherents and repelled its opponents.” The 1913 parade introduced new activism, energy, tactics, and leadership to the languishing movement. It also garnered huge national attention, both planned for, and unexpected.

No detail had been overlooked. Alice Paul made sure of it. This whole spectacle was her brainchild, and she had begun making plans and assigning tasks even before the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) had endorsed the idea or given her an official title. She badgered DC police chief Richard Sylvester into granting her a permit to use Pennsylvania Avenue. She used her connections in William Taft’s White House to make sure there was a cavalry unit standing by at Fort Myer, in case the DC police provided inadequate crowd control. She negotiated with the inaugural committee to use the grandstand constructed at 14th Street, so distinguished guests could watch the pageant in some comfort. Her public relations machine was relentless, making sure the march had been in the news so often and so thoroughly, Washingtonians almost considered it one of the formal celebrations of Wilson’s presidential inauguration.

Not all of the planning went smoothly. Paul faced a dilemma about how to handle African-American marchers, including anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells and Delta Sigma Theta, a black sorority from nearby Howard University. Paul worried southern suffragists would refuse to participate in an integrated parade. After much dithering, Paul announced black women were allowed to join, but they were not listed in the official program and were encouraged to march at the back of the procession. Wells, for one, chose to wait on the sidelines till the Illinois delegation passed by, and she marched with her white peers.

As the marchers proceeded, the large crowd jeered, grabbed them, spat, shouted, and even tripped them. Many policemen did nothing to control the crowd, and some even joined in their taunts. Inevitably, they even injured some. At least a hundred people were taken to the local emergency hospital. Finally, DC officials called in the calvary troops standing by at Fort Myer. Mounted soldiers met the head of the parade at 14th Street, and rode back up the parade route towards the Capitol, pushing the crowd back. As the Washington Post reported, “Their horses were driven into the throngs and whirled and wheeled until hooting men and women were forced to retreat.”

In many ways, the 1913 parade signaled the beginning of the final round in the long fight for the vote. In addition to earning the movement sympathetic press, the march served as Alice Paul’s debut as a leader willing to push the bounds of convention. It energized a new generation of activists to join the cause. It sowed the seeds for many more visible, aggressive tactics over the next seven years. And it announced, with a huge banner on a prominent wagon, a renewed push for a federal amendment, rather than the incremental state-by-state strategy the movement had cultivated.

Beyond the suffrage movement, the 1913 parade set the stage for thousands of political marches to follow. Every civil rights group that has marched on Washington, every activist who has paraded through the corridors of federal power to gain attention for their cause, every energetic citizen who has rallied in the shadow of the Capitol, has literally followed in the footsteps of the suffragists.

Rebecca Boggs Roberts has been many things including, but not limited to, journalist, producer, tour guide, forensic anthropologist, event planner, political consultant, jazz singer, and radio talk show host. Currently, she is Curator of Programming for Planet Word, a museum set to open in 2020. She looks forward to creating a new institution that will become part of the intellectual and cultural life of our capitol city. She is co-author of Historic Congressional Cemetery (2012), part of Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series, and author of Suffragists in Washington, D.C.: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote (2017). Roberts lives in Washington, D.C. with her husband, three sons, and a big fat dog.

Bibliography

Buck, G.V., photographer. “Woman Suffrage Parade, Wash., D.C.” Photo. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, accessed February 22, 2020.

Buck, G.V., photographer. “Woman’s Suffrage Parade, Wash., D.C., Mar. 1913,” Photo. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, accessed February 22, 2020.

Ford, Elyssa. “Woman Suffrage in the Midwest,” National Park Service, accessed February 22, 2020.

“Garfield Monument,” Office of the Architect of the Capitol, accessed February 22, 2020.

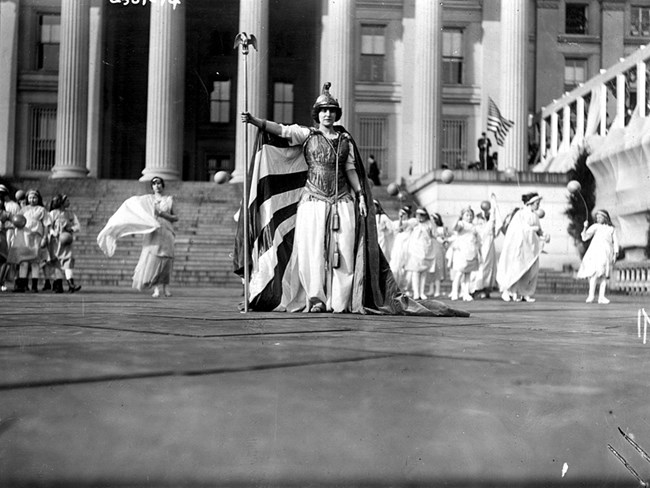

“German actress Hedwig Reicher wearing costume of "Columbia" with other suffrage pageant participants standing in background in front of the Treasury Building, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C.” Photo. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, accessed February 22, 2020

“Head of suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., Mar. 3, 1913.” Photo. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, accessed February 22, 2020

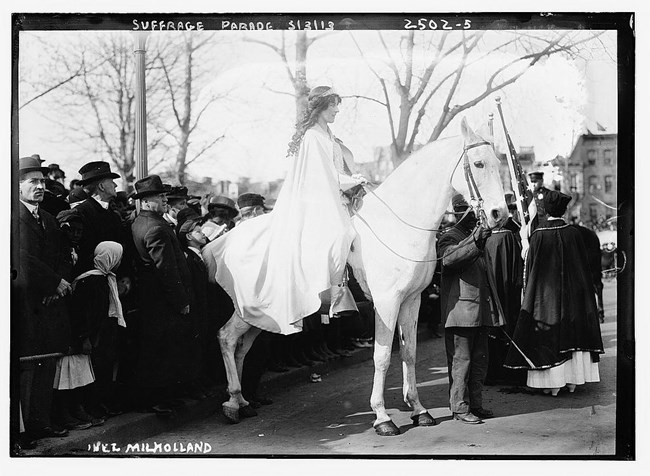

“Inez Milholland Boissevain, wearing white cape, seated on white horse at the National American Woman Suffrage Association parade, March 3, 1913, Washington, D.C.” Photo. Library of Congress, Bain Collection, accessed February 22, 2020

Lumsden, Linda J. “Beauty and the Beasts: Significance of Press Coverage of the 1913 National Suffrage Parade,” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, vol. 77, issue 3, 2000.

“Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913,” American Women: Topical Essays Series, Library of Congress: Research Guides, accessed February 22, 2020.

Moore, Sarah J. “Making a Spectacle of Suffrage: The National Woman Suffrage Pageant, 1913” Journal of American Culture vol. 20, issue 1 (Spring 1997): 89-103.

“National American Woman Suffrage Association Collection,” Library of Congress, accessed February 22, 2020

Neumann, Johanna. And Yet They Persisted: How American Women Won the Right to Vote. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2020.

Norwood, Arlisha R. “Ida B. Wells-Barnett,” National Women’s History Museum Biographies, accessed February 22, 2020

“Official program woman suffrage procession. Washington, D. C. March 3, 1913,” Library of Congress, accessed February 22, 2020.

Roberts, Rebecca Boggs. Suffragists in Washington, D.C.: The 1913 Parade and the Fight for the Vote. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2017.

“Tactics and Techniques of the National Woman’s Party Suffrage Campaign,” The Library of Congress | American Memory Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman’s Party, accessed February 22, 2020

“The Treasury Building: A National Historic Landmark,” Department of the Treasury, Office of the Curator, accessed February 22, 2020

Walton, Mary. “The day the Deltas marched into history,” Washington Post, 1 March 2013, accessed February 22, 2020

“Who Was Alice Paul? Feminist, Suffragist and Political Strategist,” Alice Paul Institute, accessed February 22, 2020

Zahniser, J.D. and Amelia R. Fry. Alice Paul: Claiming Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

“1912 Election,” The President Woodrow Wilson House, a Site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, accessed February 22, 2020

Last updated: December 14, 2020