Last updated: November 9, 2024

Article

Substitute Rangers

As the 1940s dawned, the United States was still dealing with the economic woes of the Great Depression and trying not to get drawn into WWII. Even as it continued to manage New Deal Program work in national and state parks, the NPS remained understaffed as a government bureau. The emergency relief workers and about 15 percent of NPS staff enlisted or were drafted during the first couple of years of WWII. Rationing, the need for raw materials to support the war effort, budget cuts, relocation of the NPS Washington Office to Chicago, and military use of parks all affected NPS staff and park management. NPS women—like those across America—stepped up as men went off to war.

The Calm before the Storm

In the 1940s, women continued to work as clerks and secretaries in the NPS, but few held uniformed field positions. As in the 1930s, those that did mainly worked at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, monuments in the Southwest, and historical sites in the East.

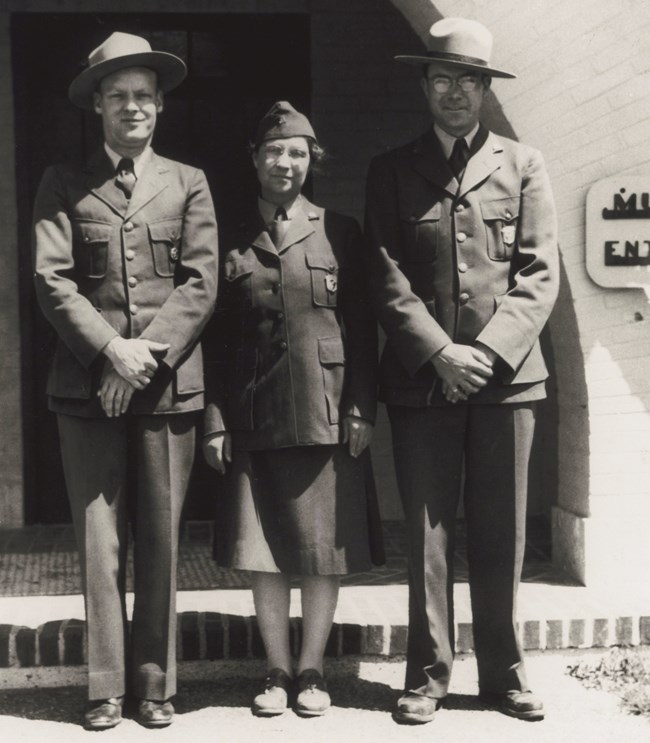

Three women held uniformed positions at Aztec Ruins National Monument in summer 1940. Little is known about Georgia Akers, Joyce Chubb, and Zelda Mae Abrams. However, their uniforms and the jobs of men photographed with them suggest that they were temporary rangers. Although the Southwestern National Monuments submitted detailed monthly reports with personnel information, no references to these women have been found in them or in newspapers accounts of the time.

El Morro National Monument’s new custodian Robert Budlong hired Elva Lorraine Tharp, known as “Sunshine,” in 1940. He couldn’t get a “relief man” because one had to be bonded to collect fees. He didn’t have any rangers or a clerk and Tharp was appealing because she lived locally. Budlong refers to her as a “rangerette” although her official personnel record lists her title as guide (see Rangers, Not Rangerettes). He recorded that although he notified headquarters that he was hiring a woman, it was his wife who gave him “full permission” to do so.

Tharp’s position began on October 3, 1940 and lasted just over a month. It paid $4 per day (when actually employed). Tharp led visitor tours, assisted with office work, and even painted park signs. Two photos of her at El Morro are known. They suggest that she wore a ranger uniform of trousers, long-sleeved shirt, boots, and a hat. However, she is painting the park sign in both and her clothing is obscured by a flowery robe, presumably worn to keep paint off her uniform.

In 1971, Budlong recalled, “She was the neatest person and thoroughly able to take care of herself. I’d see a gang coming in and we’d be in the office there. She couldn’t speak Spanish but she struggled manfully through it and she’d read the notes that I gave her to the visitors and she handled it very well indeed. I’d say ‘Sunny, here come a couple of rather rough-looking characters, you’d better let me take them around.’ She’d say, ‘No, Mr. Bob, I can handle ‘em.’ And Sunny could handle them.” Budlong’s detailed recollections of her more than 30 years after she worked for him and his description of Tharp as “a great credit the Park Service” are particularly noteworthy given how short her appointment was.

A few women worked in the Southwestern National Monuments through the National Youth Administration (NYA), a New Deal program established in 1935. Ina Mae Rinehardt, Helen Kirk, and Florence Roche worked at headquarters for a few months in 1940 on projects such as mimeographing and organizing the photograph library files. It’s unlikely that they wore Park Service uniforms.

Mariana D. Bagley had an appointment as an assistant historical aide at Colonial National Historical Park. No photos of Bagley have been found. Given that she was assigned to a new women’s uniform committee established on October 20, 1941, it’s almost certain she wore a uniform.

Uniformed women guides continued to be employed at Carlsbad as well. Myra Appell, Neta Armstrong, Alva Daniels, and Rita Walker held uniformed “nurse guide” positions. Appell also served on the uniform committee.

The Day That Lives in Infamy

From the moment the Japanese attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, women at Hawai’i National Park (now Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park and Haleakalā National Park) stepped up to serve both at the park and within their communities. The superintendent’s monthly report covering the period around the attack notes, “Guards were mobilized and assumed duty stations as rapidly as arms and identification arm bands—rushed through by park women—could be issued. . . The wives of two rangers offered their services as volunteer switchboard operators and were put on regular 8-hour shifts. Efforts are being made to get some compensation for them as well as a number of others whose services are required. All these, including fire guards and lookouts should be put on the regular rolls. There are sufficient funds and formal request will be made shortly.”

He also noted that, “The park women made bandages, continued their knitting and sewing for the Red Cross and later were authorized to take over the warehouse job and the issue and delivery of kerosene, firewood, etc. to release the men for other work.” His term “park women” included both NPS employees and the wives of park men. One of the employees who responded was Constance Whitney Hewitt, the park’s clerk-stenographer. Although not mentioned, assistant clerk-telephone operator Winifred H. Tada probably also responded as she and Hewitt were the only women employed at the park as of November 1941.

Tada, born in Honolulu to Japanese parents, was certainly familiar with emergencies. She started working at the park on January 9, 1940, and a month later she discovered the fire that destroyed the historic Kilauea Volcano House. Her quick actions allowed guests to safely escape the burning hotel. Tada, who had been living at the hotel, lost all of her clothes in the fire. We don’t know exactly when she stopped working for the NPS, but by 1942 she was employed elsewhere. Throughout the war, she worked at area schools and volunteered with a group of women that held fundraisers for polio relief and made sandals for wounded soldiers recuperating on the island.

One “park wife” featured prominently in the report of the events. At Haleakala, Catherine Rouse Hjort played a critical role in alerting the men in that district of the attack. As it happened, the men were “in the crater and out of touch with the commanding officer of the local air unit when the attack was being carried out at Pearl Harbor.” The naval officer in charge called Mrs. Hjort. As she was the nearest person to the men in the crater, she went herself. Since she couldn’t take her five-year-old daughter, Marbeth Anne, she had to leave her alone until friends could come look after her. “Mrs. Hjort proceeded into the crater, making good time, and notified the men to come out which they did with great haste. The entire force of Navy men based on Maui phoned Mrs. Hjort their thanks for her efforts.” Later that month, Ranger Hjort taught her how to use the fire hoses and extinguisher equipment in case a fire broke out when she was alone.

In the year leading up to the United States entering the war, park women were already making contributions. At the end of his summary of the events of and immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Superintendent Edward G. Wingate wrote, “I also wish to mention the following past and present park women who along with other duties, including work on the home gardens, during the year completed for the Red Cross a total of 58 sweaters, 4 scarfs, 1 shawl and 20 pairs of socks: Mrs. Frank Huston, Mrs. Lynn Waecshe, Mrs. Grace Schultz, Mrs. Margaret Miller, Mrs. Margaret Jess, Mrs. Constance Hewitt, Mrs. [Elizabeth] Wingate and her maid, Marie Kanno.”

The Call to Serve

Although women could not fight on battlefields in WWII, many still enlisted in women’s units to serve their country.

One of the earliest NPS women to leave her position for war service was Beatrice Ball, the first woman officer hired by the US Park Police and A Long-Awaited Asset. When she was hired in January 1942, she came with a decade of experience as an officer with the Metropolitan Police in Washington, DC. However, she only wore her US Park Police uniform for about six months before she left the NPS. Determined to have a “more concentrated war job—not just fooling around with some halfhearted efforts,” she joined the women’s branch of the US Navy (WAVES). After the US Coast Guard Women’s Reserve (known as SPARS) was established, she transferred there. She was one of 13 in the first class of women to attend the Coast Guard Academy. She became the first SPARS officer assigned to the Coast Guard’s Office of Intelligence. During the war she worked as an intelligence officer at several cities on the East Coast. Ball never returned to the NPS, continuing her career with the Coast Guard instead. She retired with the rank of commander in 1961.

In another example, Marianna Bagley Doust left her historical aide position at Colonial National Historical Park in 1942 to serve in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC). She returned to duty at the park three years later. Betty E. Vilm, a clerk-typist at Crater Lake National Park since June 1941, joined the WAC in February 1943. She spent over a year of the war in England and France. She was discharged as Captain Vilm and returned to her park job as a bookkeeper in January 1946. Evelyn E. Kumor, clerk-stenographer at Yellowstone, joined the WAVES in November 1944. She was released from the US Navy to return to the park in June 1946. Roberta Whittington, a guide at Carlsbad Caverns, was sworn in to the WAC in January 1944. Whittington, with her geography degree, enlisted to do cartography and topographical drafting, a field that had just opened to WAC women. There were undoubtedly many others who served as well.

A Wartime Superintendent

In a groundbreaking appointment, Gertrude S. Cooper, a widow with three children, became the first woman superintendent in the NPS in June 1940 (see Women Who Were There for the first woman custodian). When the US joined the war within 18 months of her appointment to Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, she became the first wartime woman superintendent.

The proximity of the mansion to the Roosevelt’s home created unique management challenges during WWII. From 1941 to 1943, up to 35 members at a time of President Roosevelt's Secret Service detail were housed in service areas at the mansion. In a delicate situation for any superintendent, Cooper became concerned about female visitors in the summer of 1942. She wrote the White House, “I should like to bring to your attention a policy which I intend to enforce rigidly. . . . No women visitors will be allowed in the Mansion after official visiting hours.”

When the Secret Service agents and secretarial staff occupying the house left in May 1943, the US Military Police arranged to use the entire third floor of the mansion for the duration of the war. Beginning in late 1943, Cooper established a canteen where soldiers could have coffee and “dance or chat or play games” with local women.

Although no photographs of her in uniform have been found, as a superintendent she would have been expected to wear one. She was also on the 1941 uniform committee with Bagley and Appell, further suggesting that she did, in fact, wear one.

Unlike many women during WWII, Cooper didn’t step in to fill a job that “belonged” to a man that she would then lose upon his return at the end of the war. However, she chose to resign from the NPS in May 1945, shortly after President Roosevelt’s death. See Career Women to learn more about Cooper’s other accomplishments as the first woman superintendent.

War Service Appointments

Executive Order No. 9063, signed on February 16, 1942, expedited recruitment for federal positions during the war period. However, it deferred filling permanent vacancies because so many in the armed forces and related war industries were unavailable to compete for them. As a result, men and women received “war service appointments” for jobs in national parks. These temporary appointments didn’t require Civil Service exams. Two of the women who received this type of appointment were already familiar NPS faces with impressive credentials.

Sallie Pierce Brewer Harris, an archeologist and Honorary Custodian Without Pay (HCWP) in the Southwestern National Monuments in the 1930s, received an indefinite war service appointment on February 16, 1943. She worked as a park ranger at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument until the following June when she transferred to Tumacacori National Monument. Ranger Jessica W. Shearwood from New York replaced her at Casa Grande in July 1944.

Brewer Harris remained in the Southwest even after her war service appointment ended. Throughout the 1950s and until her retirement in 1967, she held a series of temporary ranger, naturalist, and archeologist positions at Grand Canyon National Park and Bandelier, Casa Grande, and Walnut Canyon national monuments. She also held two separate permanent archeologist appointments at the Region III Office before she retired from the NPS in October 1967.

Archeologist Jean McWirt Pinkley received a war service appointment at Mesa Verde National Park in May 1944. In 1941, she was the chair of the women’s uniform committee. From 1939 to 1943, she had a permanent (subject to furlough) museum assistant position at the park. She declined to return to the position on May 29, 1943, to spend time with her husband, Addison B. Pinkley (son of Superintendent Frank “Boss” Pinkley of the Southwestern National Monuments), before one of his deployments. Lieutenant Pinkley was killed in action when the Japanese sank his submarine USS Gudgeon in 1944. Pinkley was reinstated to her permanent position after the war and continued a remarkable career as an NPS archeologist and chief of interpretation until her death in February 1969.

NPS “Rosies”

As more men were drafted during WWII and parks had difficulty finding men rangers, some women stepped into these uniformed positions. Inevitably, as they did so the unfortunate “rangerette” title briefly resurfaced in the newspapers (see Rangers, Not Rangerettes).

One woman given that made-up title by the media was Ethel L. Meinzer, a clerk-stenographer at Rocky Mountain National Park. She was asked to step in at Scotts Bluff National Monument when two male rangers were called to serve. On August 3, 1942, she became the first woman to wear the uniform at that park. Although she described her new ranger job as “more interesting than pounding away at a typewriter all day,” she still had to do clerical duties in her new role, which included registering visitors and looking after the park’s museum.

Newspaper accounts noted that she wore the “regulation olive drab uniform of the park service [sic], except that it is fitted with a skirt instead of trousers, a barracks hat instead of a broad-brimmed hat like rangers wear.” Expressing her disappointment, Meinzer stated, “I think I would have preferred a hat. It would have been more attractive—and more suitable for wearing out in the sun, but this is what they gave me and it’s all right.” Meinzer returned to her clerk job at Rocky Mountain in May 1943. She was promoted in June 1945 to personnel clerk at Glacier National Park, where she remained until she retired in 1956.

Pinnacles National Monument hired two local woman to fill vacancies created by the war. Clara J. (Ann) Lausten was hired as a clerk-typist in October 1942, becoming the first woman to work at the park. When she arrived, there were only three other full-time employees. Custodian W.I. Hawkins decided that she should wear the NPS uniform. She earned $144 per month, but in 1996 she recalled, “Mr. Hawkins insisted, and I mean insisted, that each employee sign up to purchase war bonds—so we did!” She also recalled that she purchased “some wool ‘forest green’ material that was used for military officers’ uniforms” and had a friend’s mother make her two skirts. She wore the regulation gray shirt, green tie, an overseas cap, brown shoes, and “the NPS pins on my shirt.” The pin on her overseas cap shows that she had a family member (her husband Ken) in the armed forces. She worked at the park until June 1945 when the clerk- typist and custodian positions were combined. Drucilla Maltby Isaacson was hired as the park’s first woman seasonal ranger around 1943. Although no photos of her have been found, she likely wore a uniform similar to that of Lausten.

At Carlsbad Caverns, the number of women grew as Anita Armstrong, Alberta Turrill, and Madge Bryan joined the staff in 1941. Superintendent Thomas Boles hired women to fill other positions as well. Helen T. Kennicott and Betty Milam were in the finance department. Anna McMichael, Mineola Everage, Edna Seaton, and Viola Shannon were part of the maintenance crew, responsible for building interiors. Ruby I. Warehime was Boles’ secretary. Roberta Whittington joined the park in fall 1942 as a guide. She was one of the few guides hired without a nursing background. By 1943 there had been some turnover, but Appell, Bryan, Whittington, Kennicott, McMichael, Everage, Shannon, and Warehime were still at the park. They were joined that year by Ruth A. Makins.

Carlsbad Caverns has a history of hiring uniformed women guides that goes back to at least 1930, so it isn’t surprising that they had so many women employees during WWII. However, the park was an exception, not the rule. Herbert Kahler, NPS chief historian from 1954 to 1964, noted the NPS “never really gave serious thought to using women during WWII.” Throughout the war, the NPS had a custodial mindset, protecting its resources to the best of its abilities under the circumstances until normalcy returned after the war. As such, most women in uniform were merely placeholders until men could return.

Although a few women like Harris, Pinkley, and Meinzer were able to carve out careers with the NPS, most could not. For many women during the war, their NPS experiences were more akin to substitute teaching as they were called in as needed with few prospects for longer-term employment.

Twenty-five years after Ranger Helene Wilson worked at the Nisqually entrance station at Mount Rainier National Park, Barbara Dickinson and Catherine M. Byrnes took up the post in 1943. Like Wilson, they issued vehicle permits, collected entrance fees, recorded license information, and provided general information to visitors.

Dickinson was teaching school and driving a school bus when the park hired her, but she wasn’t an unknown quantity. She had spent several summers in the park since 1934 when her father worked as a diesel mechanic. She had also worked as a telephone operator during the summer of 1942. In an oral history she recalled that Chief Ranger Oscar Sedergren visited her at her home in Maple Valley and asked her to come to the park the next weekend. She did and they offered her the ranger job for summer 1943. Dickinson noted that she was the “logical choice” as she had her own car, knew the area, and had hiked many of the park trails already.

Dickinson recommended fellow teacher Byrnes for the second ranger position. Together the women lived at the Nisqually ranger station and worked opposite shifts. Byrnes continued teaching and therefore worked shorter seasons but Dickinson generally worked from May through the fall hunting season. She described her time as a ranger noting, “It was a good life in the park. We’d work all day, dance at the hotel at Paradise, go home change our clothes and hike Eagle Peak in the moonlight.”

Women’s interest in working at Mount Rainier continued in 1944. A park report notes, “Some applications have been received from women indicating a desire to be placed in the protection department. It has been decided to employ only the two girl rangers who worked at Nisqually Entrance last season, and who have indicated their intention to return.” Both Dickinson and Byrnes worked the 1944 and 1945 seasons. Due to her loyalty to the NPS, Dickinson delayed her wedding until October 1945 so that she could complete her commitment to the park and continue working until September of that year.

Dickinson received a national award for her design for a new entrance station mirror that allowed rangers to see a car’s license plate without leaving the booth. In 1999, she recalled, “There was not another woman ranger for 27 years,” suggesting humorously “either I blew it, or my shoes were hard to fill.”

Devils Tower National Monument hired two temporary women rangers during the war. Ranger Nellie B. Wenande worked for six weeks in 1943. Her position was filled the next year by Alice L. Hauber who worked a longer season from June 2 to September 22. Hauber returned for another 10 weeks in the summer of 1945. In 1946, her position was filled by a man.

Holding His Place

Herma Albertson Baggley resigned her permanent ranger-naturalist position at Yellowstone in 1933. The late 1920s and 1930s efforts geared towards Protecting the Ranger Image had been so successful that nothing short of a world war could bring women rangers back to Yellowstone National Park. Even then, fewer women were hired and for less time than might be expected.

In 1941, five women were employed as emergency fire guards on secondary lookouts, but they were not uniformed. Four were wives of permanent rangers, and one was the wife of the principal storekeeper. Two of the women alternated at the Bunsen Peak Lookout, walking approximately six miles each day to and from the lookout. The wife of the district ranger at Canyon rode horseback 16 miles each day to the Observation Peak Lookout.

In 1942, Yellowstone reported, “The loss of both permanent and seasonal rangers during the latter part of the 1942 season made it necessary to employ six women as seasonal rangers to assist in the operation of the North and West Gates and the information desk at Old Faithful.” Ironically, these were the same jobs that the early women rangers were doing in 1926 when Superintendent Horace M. Albright declared, “There are no women rangers in Yellowstone Park doing ranger work.” Before the year was out, a total of seven women had been hired as temporary rangers. However, this was hardly a renaissance for women rangers at that park, as they were often given incredibly short appointments.

Arguably the most familiar and surprising name among the seven is Marguerite Lindsley Arnold. Her ranger career in the park began in 1921 and in December 1925 she became the first permanent woman ranger in the NPS. She resigned her permanent position in 1928 when she married fellow ranger Ben Arnold. She continued to work as a temporary ranger until she resigned again in 1931 (see How Would You Like to be a Ranger?). Eleven years later, she was a ranger for a total of seven weeks. In the 1920s and early 1930s, she wore the standard Park Service uniform with an approved alternative coat. It’s not known if she donned her uniform and Stetson hat again in 1942 or wore civilian clothes.

The other women rangers in 1942 were Kathryn Bauman, Marjorie A. Sommerville, Margaret E. Watson, Lois Kowski, Louise E. Chapman, and Esther M. Johnston. It’s not known how long Johnston worked but both Bauman and Sommerville had appointments that only lasted three weeks.

Chapman and Kowski lived next to each other in a duplex and shared their ranger work as well. Both women recalled that they alternated mornings and afternoons between the West Yellowstone entrance station and fire lookout duties. Records indicate that Chapman’s 1942 appointment was for five weeks whereas Kowski’s only lasted three days. Both women certainly worked longer than that, but it’s likely that they weren’t paid for their efforts. In an oral history interview Chapman recalled doing various jobs and “being paid but it was only temporary things when they completely ran out of rangers.” Although she “was bonded” (which was required to handle money) she “wasn’t serious enough to get a uniform for” in 1942 and wore her “regular clothes while checking cars through.” Given that their appointments were so short, it’s unlikely that the other women wore NPS uniforms either.

Most of these women rangers worked at entrance stations, checking cars in and out of the park, sealing guns, and collecting entrance fees. Chapman recalled that sealing a gun involved “a wire that went down the barrel, then you bring it back and there is a little metal seal, you stick it through and you pinch it that puts US Park Service on it.” The seals were removed with wire cutters upon leaving the park.

Margaret Watson was one who didn’t work at an entrance station. Her September 15, 1942 appointment lasted less than two weeks and she only worked part time. In an oral history interview she recalled spending her mornings at the information desk at the Old Faithful Museum while another woman worked the afternoon shift. Training wasn’t provided but as a ranger’s wife who had lived in the park for a couple of years, she “did as well as the new rangers coming in for the first time anyway.” Watson recalled that she took her four-year-old son Kent to work with her each day as he was recovering from head injuries sustained in a bear attack that June. He’d been saved from the bear by another ranger’s wife but spent several weeks in the hospital recovering from a fractured skull, badly torn scalp, and lacerations. His head was still heavily bandaged when he accompanied his mother to work. Watson noted that she didn’t wear an NPS uniform because “it was an emergency thing.” She resigned on September 27, 1942 as the tourist season had dropped off but she continued to live in the park with her family for several seasons, including one winter.

In spite of the ongoing war, no women rangers were hired at Yellowstone in 1943. In 1944, only Nancy R. Bowers worked as a park ranger, staffing the northeast gate for almost three full months. The next year she was replaced by Louise Chapman who worked from June 11-September 22, 1945. This time, Chapman “had a uniform and the whole business.” In an oral history interview, she noted that although women wore the uniform skirt, she had found “in very small print” that women “may wear slacks. So that’s what I got.” She wore tailored ladies’ slacks that she described as “a good fit and very nice” and “the regular jacket.” She noted that a skirt would have been impractical given the half-mile distance through woods between the old cabin where she lived and the entrance station where she worked. She recalled working briefly on Gardiner gate as well, “until they didn’t have any more use for temporary rangers.”

The “one off” and short appointments that the women rangers had during WWII belie the idea that there were renewed NPS opportunities for women in uniform during the war. For most women, their NPS experiences were more akin to substitute teaching. They were called in as needed with few prospects for longer-term employment. Seemingly, women were only hired when it couldn’t be avoided, to cover a schedule before visitation dropped off at the end of the season, or when men were sick, on leave, or temporarily absent from the park. In short, they provided some flexibility for the NPS without threatening the status quo.

Rising from the Ranks

Morristown, New Jersey native Vera B. Craig is a rare example of a woman who served in WWII before joining the NPS and yet was able to build a career with the bureau. She served with the Coast Guard SPARS from 1943 to 1946. She was then hired as a museum aide at Morristown National Historical Park.

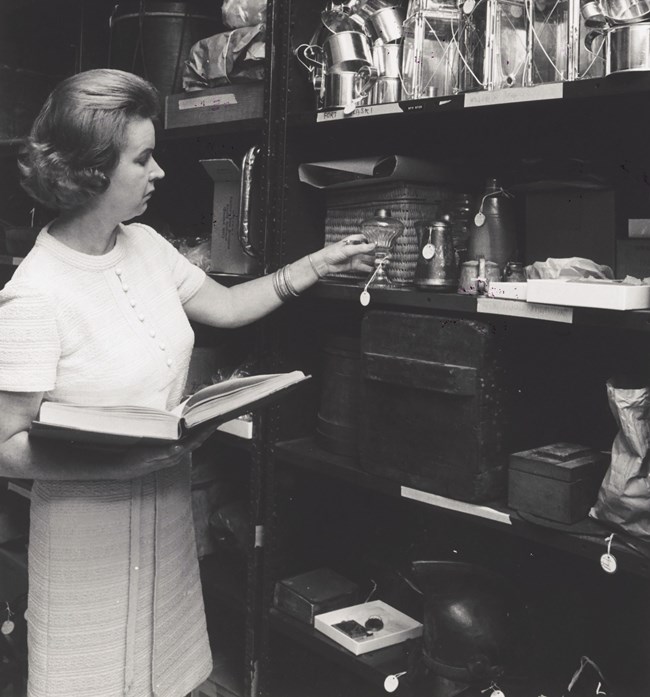

In an oral history interview, Craig reflected that while at Morristown she didn’t get the raises that a man in her position would have. In May 1957, she transferred from Morristown to the NPS Museum Branch in Washington, DC as a curator. Craig played a key role in establishing NPS records practices for museum collections and training staff in parks.

She became a historic furnishings specialist, a job which included researching, writing, and implementing a wide variety of furnishing plans for historic houses throughout the NPS. Examples include the homes of President Andrew Johnson and Frederick Douglass. In 1963, Craig worked with First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy on the redecoration of the White House.

Craig retired from the NPS after a 30-year career. She died on December 25, 1982, at age 61.

New Day, Same Limitations

On February 4, 1946, President Harry S Truman signed Executive Order 9691, restoring normal Civil Service hiring procedures for federal positions. In the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, most uniformed NPS positions continued to go to men, particularly veterans. Although female members of the armed forces were included in the Veterans Preference Act of 1944, they accounted for only 2.1 percent of WWII veterans, and the odds weren’t in their favor.

Carlsbad Caverns remained the employer of the most uniformed women in the NPS in the late 1940s, most of whom worked as guides. Archeologists Harris and Pinkley continued to work in parks in the Southwest.

Although a handful of women like Harris, Pinkley, Craig, and Meinzer were able to carve out careers with the NPS, most could not. A small number of women managed to get temporary uniformed positions after the war as guides, historical aides, or similar positions. In November 1946 Cara Robinson, wife a Navy officer, gained a very brief temporary appointment as a historical aide until December 1, continue the war-time trend of offering women short-term positions when it was convenient for the NPS. Mildred Ericson became a temporary ranger-naturalistat Yellowstone in July 1946. She returned to the park each summer for 20 years without getting a permanent job with the NPS. Temporary ranger-naturalist Mary L. Oswald joined Ericson but only for one season.

Although a handful of women eventually got permanent uniformed jobs in the 1950s, most would still have to wait another decade for the door to open more than just a crack.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.

Tags

- aztec ruins national monument

- bandelier national monument

- carlsbad caverns national park

- casa grande ruins national monument

- colonial national historical park

- crater lake national park

- el morro national monument

- grand canyon national park

- haleakalā national park

- hawaiʻi volcanoes national park

- mesa verde national park

- mount rainier national park

- pinnacles national park

- rocky mountain national park

- scotts bluff national monument

- tumacácori national historical park

- vanderbilt mansion national historic site

- walnut canyon national monument

- yellowstone national park

- nps history

- women's history

- nps careers

- uniforms

- hfc