Last updated: March 1, 2023

Article

Rangers, Not Rangerettes

In spite of the United States entering World War I in April 1917, visitation to national parks increased by 36 percent in 1917 over the previous year. With more park roads, increased railroad and automobile touring, and improved hotels and other services—and despite the outbreak of the Spanish Flu pandemic that spring—the National Park Service (NPS) expected another record summer in 1918. Increasing visitation and a lack of qualified men, coupled with educated women being in the right place at the right time, created opportunities for a few more women to become park rangers.

The Winds of Change saw Esther Brazell at Wind Cave National Park become the first woman ranger beginning in 1916. Other women rangers weren't hired until 1918. Although Freeda C. Nielsen at Wind Cave had a teaching background and a connection to Esther Brazell, lack of qualified men rangers may have been one of the factors that led to her selection. For the other two confirmed women rangers hired in 1918, WWI was certainly an important (but still not exclusive) factor in their hiring.

"The Right One"

Born on December 1, 1890, Clare Marie Hodges attended San Jose College where she particularly enjoyed botany. In 1904, when she was just 14 years old, she rode with her family rode on horseback for four days to reach Yosemite Valley. She also made trips to Tenaya Canyon and from Yosemite Valley to Tuolumne Meadows. After her first visit to Tuolumne Meadows in 1913, she returned five or six more times.

Hodges felt intimately connected to Yosemite, and several of her poems were published in 1914. In 1916, she began teaching at the Yosemite Valley School, becoming even more familiar with Yosemite’s landscapes and trails.

In the spring of 1918, Hodges, 20, heard park rangers talking about how hard it was to fill the ranger positions left vacant by men fighting in the Great War. With two years of preparation as a teacher in Yosemite, she applied to W. B. Lewis, the park’s superintendent. She told him that he "would probably laugh at her," but she wanted to be a ranger. Lewis replied that he "already had it in mind to hire a female ranger but hadn’t found the right one." Hodges was hired as a temporary ranger on May 22, 1918. She was given a badge and a salary of $75 per month.

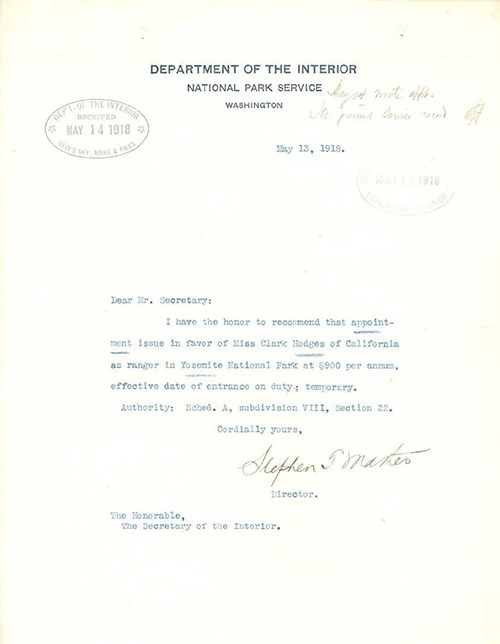

Her official appointment letter is on Department of Interior letterhead, dated May 13, 1918 and stamped received May 14, 1918. It reads:

Dear Mr. Secretary, I have the honor to recommend that appointment issue in favor of Miss Clark [sic] Hodges of California as ranger in Yosemite National Park at $900 per annum, effective date of entrance on duty; temporary. Authority: Sched. A, subdivision VIII, Section 22. Cordially Yours, Stephen T. Mather, Director

The Honorable,

The Secretary of the Interior

Her temporary position only lasted about four months. A newspaper account at the time described her job as “whatever the chief ranger wishes her to do” including performing mounted patrols, answering his telephone, preparing reports, registering tourists, sealing firearms, assigning campgrounds, counting campers, issuing car permits, and collecting gate receipts. Hodges recounted in 1925 that she also “had the power of arrest.” She didn’t wear a uniform, but that didn’t necessarily make her The Odd “Man” Out.

As a ranger, Hodges rode horse patrol through remote areas of Yosemite. She reported to the chief ranger just as the male rangers did. Her duties included taking the gate receipts from Tuolumne Meadows up to park headquarters, which was an overnight ride on horseback. The NPS didn’t have an official uniform until 1920. Hodges wore a divided skirt and a middy blouse. She donned the same Stetson hat as her male counterparts but refused to carry a gun.

After her temporary ranger position expired on September 7, 1918, she married Earl L. Seiverson. Together they had one son, Forest Glen born in 1920. The circumstances surrounding the end of her first marriage are unknown, but she married Peter-Wolfsen, a Mariposa ranger, in 1925.

She worked as a naturalist at a Seven-Day Adventists’ summer camp at Wawona, teaching botany and horsemanship and establishing nature trails. After 33 years of marriage, Wolfsen died on July 29,1958 in Yosemite Valley. In 1963, at the age of 72, Clare married Ernest J. Morris in Tulare, CA. They were married for seven years before she died of cancer on June 20, 1970 in Loma Linda, CA. She is buried at the Merced Cemetery.

In Lieu Of A "Suitable Man"

Born January 21, 1888 in Robinson, Illionois, Helene Harper Wilson moved to Washington with her family as a young child. Although she married Thomson C. Wiggins in 1912, they were divorced sometime before 1919. There's no record of her educational background.

On June 6, 1918, Mount Rainier National Park Superintendent Dewitt L. Raeburn sent a telegram to the NPS director stating, "Have not found suitable man for issuing permits at entrance" and asking "Will it be practicable to appoint for this position Miss Helen [sic] Wilson formerly assistant secretary Seattle Automobile Club?" A return telegram from Horace M. Albright the next day informed him that he could "appoint Helen [sic] Wilson temporary ranger." The Department of Interior formally appointed her on June 17, 1918, "effective on the date of entrance on duty." Wilson, 30, started the job on July 1, 1918.

Ranger Wilson earned $90 a month, the same salary as four men rangers hired at the same time. Her duties included registering cars at the park entrance station and issuing permits for picking wildflowers. In a September 30, 1918, memo, Superintendent Raeburn recorded, "Miss Wilson's services were terminated after the Labor Day rush, partly because there was no further urgent need for her there and partly because of her desire to take up other work in Seattle." He also noted that he recorded the "the termination of her services was due to expiration of the appointment" but if that was inconsistent, "it may be changed to agree with the facts."

No photographs of Wilson are known from 1918. Her official government personnel record indicates that she only worked that one summer as a ranger. Yet it wasn't until May 27, 1920, that an article entitled "Distinction: First Woman in Northwest to be Forest Ranger" was published by the New York Daily News. The brief article describes her as "the first woman forest ranger appointed by the United States in the Northwest" and notes that she was stationed at Mount Rainier. It goes on to note that she is "one of five holding similar positions in the entire country." It's unclear why it took two years for the article to run in the newspaper if she was only employed in 1918.

A photograph of Wilson accompanied the 1920 article. If taken during her employment as a ranger, it suggests that she wore a white middy blouse, neck kerchief, and a coat. The image doesn't show enough of the uniform to determine if she was wearing the authorized 1917 uniform coat but the notched lapels are similar in style.

After her summer with the NPS, Wilson worked as a stenographer and secretary. She married Logan S. Paine in 1922 but they later divorced. In 1935, she married Edmund A. Burke and together they visited Mount Rainier in 1937 where she shared her ranger experience with the staff there at the time. She was widowed and World War II found her working as a clerk for the U.S. Navy in New York. She died on May 22, 1945, in Manhattan.

The Other 1918 Women Rangers?

Like the 1920 Daily News article, a 1937 Park Service Bulletin newsletter reports that three other women were park rangers in 1918. It reads:

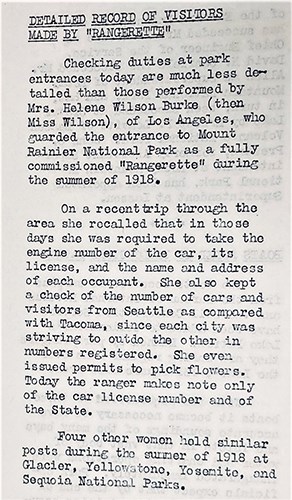

Detailed Record of Visitors made by "Rangerette"

Checking duties at park entrances today are much less detailed than those performed by Mrs. Helen Wilson Burke (then Miss Wilson), of Los Angeles, who guarded the entrance to Mount Rainier National Park as a fully commissioned "Rangerette" during the summer of 1918.

On a recent trip through the area she recalled that in those days she was required to take the engine number of the car, its license, and the name of each occupant. She also kept a check of the number of cars and visitors from Seattle as compared with Tacoma, since each city was striving to outdo the other in numbers registered. She even issued permits to pick wildflowers. Today the ranger makes note only of the car license number and of the state.

Four other women hold similar posts during the summer of 1918 at Glacier, Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia National Parks.

Interestingly, the article leaves out Wind Cave National Park where we now know Freeda C. Nielsen worked in 1918. The names of the women rangers reported to have worked at Yellowstone, Glacier, and Sequoia national parks aren’t known today—if the report is accurate. The recent discovery of the earlier 1920 newspaper article lends support for a total of five women rangers in 1918 but it's suspicous that no NPS records or newspaper accounts of women rangers at those parks have been found.

It's possible that the 1920 article, which refers to forest rangers rather than park rangers, includes women rangers who worked for other government departments. Early newspaper accounts often used park ranger, forest ranger, and even mountain ranger interchangeably. The 1937 article, however, lists specific parks where the three worked. It's possible that the source of that information was Wilson and that she was simply mistaken (or quoting the 1920 article).

It's also possible that the editors of the Park Service Bulletin confused the timeline of women rangers at those parks. For example, ranger Isabel Bassett Wasson was at Yellowstone in 1920, not 1918. Maude Magly, wife of ranger George Magly, was at Sequoia as early as 1920. Although the park benefited from her efforts for years, it's not clear that she was ever on the payroll. Mary J. Sullivan worked as a temporary ranger at Glacier in 1925 before becoming permanent in 1926 but 1918 is too early for her.

Another possibiltiy is the women were licensed guides or women who worked for park concession operators rather than the NPS. Without more information, the report remains just an interesting possibility. However, the newsletter article did have one significant long-term effect on how the public and many NPS employees describe women rangers.

Adding Editorial Flair

Brazell, Nielsen, Hodges, and Wilson had traditional park ranger duties to go with their park ranger job titles. At each park, men were hired to do the same jobs that they did. Yet over time, they (and others who came after them) were often called “rangerettes” rather than rangers. There is no evidence to suggest that they were called that in 1918. Although the term is found in a newspaper article from November 1919, it was used in reference to an infant daughter born to a Forest Service ranger, not an adult women. The first use of the term for NPS women was in a June 30, 1931, newspaper article in reference to ranger-naturalist Herma Albertson.

The earliest use of the term within the NPS is in that same 1937 Park Service Bulletin article mentioned above. It’s likely that the headline was created for editorial flair. Searches of online newspapers finds the “rangerette” or “ranger-ette” descriptions crop up in the broader press during World War II and then infrequently through the late 1960s. It becomes more popular beginning in the 1970s, referring to women rangers in both national and state parks.

It’s perhaps not surprising that the diminutive and feminine word’s increasing use within the NPS and in broader American society coincided with women’s calls for equal rights. There is no evidence to suggest a deliberate or coordinated campaign to diminish the role of NPS women with a title like “rangerette,” but arguably that’s what it does. Certainly, the title carries less authority than that of ranger. Consider also, the word’s increasing use in the 1970s when the women’s uniform was dramatically different from that of the traditional ranger, and the effect is magnified.

Making Headlines

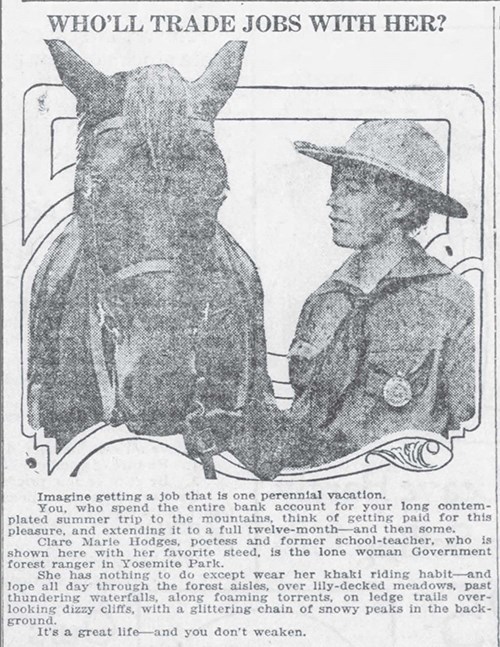

Hodges’ appointment ended September 7, 1918, but public interest in her was just getting started. An article appeared within a week, featuring a picture of her and her horse. The dismissive tone is evident with descriptions such as, “She has nothing to do except wear her khaki riding habit—and lope around all day through the forest aisles, over lily-decked meadows…” Later syndicated newspapers and magazine articles better reflected and respected her ranger position. These articles from the late 1910s and 1920s refer to her as a ranger.

Text for the article reads:

WHO’LL TRADE JOBS WITH HER?

Imagine getting a job that is one perennial vacation.

You, who spend the entire bank account for your long contemplated summer trip to the mountains, think of getting paid for this pleasure, and extending it to a full twelve-month—and then some.

Clare Marie Hodges, poetess and former school teacher, who is shown here with her favorite steed, is the lone woman Government forest ranger in Yosemite Park.

She has nothing to do except wear her khaki riding habit—and lope all day through the forest aisles, over lily-decked meadows, past thundering waterfalls, along foaming torrents, on ledge trails in the background.

It’s a great life—and you don’t weaken.

Interest in Hodges’ story continued throughout her life—and beyond. Brazell and Nielsen didn't get the publicity that Hodges did even though they were hired first. As a result, for a century, Hodges was incorrectly believed to be the first woman park ranger.

The public interest in the novelty of women park rangers also extended to many of those hired after Hodges. Inevitably, the “rangerette” headlines are still periodically recycled, particularly around NPS anniversaries and even women’s history events. “Rangerette” was never an official NPS job title. It’s time to push back against the headlines that celebrate a perceived cuteness of women “rangerettes” over the competence of women rangers.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.