Last updated: October 20, 2023

Article

Protecting the Ranger Image

In 1926, five women rangers worked in Yellowstone National Park. Marguerite Lindsley was the only permanent ranger and supervised the museum at Mammoth. Frieda B. Nelson and Irene Wisdom were temporary park rangers. Wisdom worked at the entrance station, while Nelson did clerical duties in the chief ranger’s office and worked in the information office. Rangers Frances Pound and Elizabeth Conard both worked with their park ranger fathers. Yosemite had at least three women rangers that same year. None of them could have predicted that the ground gained by women rangers in the early 1920s was about to fall from under their feet.

The He-Man Force

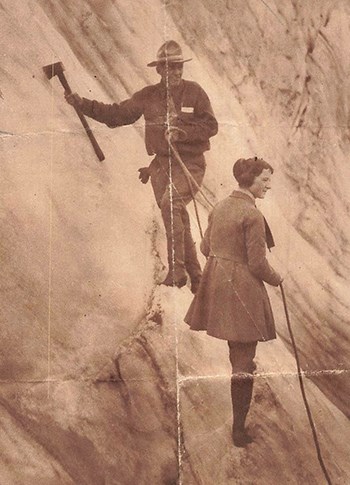

Although media coverage of women rangers in the early 1920s was universally positive, within the Department of the Interior (DOI) and the NPS there was a growing backlash against them. At Yellowstone, women rangers wore the NPS uniform, which probably added to the sense that they were encroaching on manly ranger territory. Even some of the men who hired the women didn’t like the idea of them on what Yellowstone’s Superintendent Horace M. Albright described as a “He Man force.”

On August 25, 1925, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work issued Order Number 76, directing the chief inspector to make a survey of the NPS to “study its organization, including personnel, and suggest changes in methods and policies, if needed, to improve the Service or reduce its costs.” Almost exactly a year later, two inspectors made their official visit to Yellowstone. Their report included a recommendation against hiring women as rangers and expressed the belief that women were not physically suited to “the arduous duties of a ranger and that the service, which is already under-manned, suffers by the loss of what a qualified man in her place could perform.”

Women’s Work

In his response to the report, Albright stated, “There are no women rangers in Yellowstone Park doing ranger work.” He did point out inaccuracies and pushed back against what one disgruntled man had reported. However, he also noted that giving the ranger title to these women was unavoidable due to Civil Service regulations. He emphasized their naturalist and clerical duties and described them as doing jobs that men were uninterested in or where they were “more or less useless.” He also somewhat grudgingly acknowledged that “if we are going to keep our organization in the highest efficiency, we may have to employ a few women.”

Albright seems to have had a convenient view as to who was doing “ranger work” and who wasn’t. As of July 1926, Yellowstone had 29 permanent and 54 temporary rangers on duty for the summer season. Of those, just five were women. Two (Pound and Wisdom) worked at entrance stations. If they were not doing “ranger work,” then neither were the men doing the same jobs at the same stations.

It’s particularly vexing that Albright believed that Frances Pound was not doing ranger work. In an oral history interview in 1981, she stated that she carried a sidearm as a ranger. She also recalled one incident where she and her father arrested a pair of robbers. In 1927, Albright himself publicly acknowledged her when she arrested three employees after suspecting them of transporting liquor into the park. The men pleaded guilty and the newspaper account of the event noted, “Ranger Frances Eva Pound, permanent girl ranger of the Yellowstone National Park ranger force, is credited with having made the most important arrest of the season.”

As for the other three women working in 1926, they certainly did a lot of education work. However, so did men rangers. Opening day that year was June 20. From then until the end of the season, the park had 174,800 visitors. It’s laughable to think that Lindsley, Conard, and Nelson provided all of the lectures, information services, and naturalist trips for that volume of visitors, even with concession operators providing additional services in the park. (And if they did, what were the other 54 temporary rangers doing?).

Even a cursory review of Yellowstone’s staff list that summer reveals familiar names of men like Dr. Henry S. Conard (Elizabeth Conard’s father no less!) and Dorr Yeager, who did naturalist work at that time under the park ranger title. In fact, three permanent and three temporary men rangers that year contributed articles for Yellowstone’s 1926 Ranger Naturalist Manual as Lindsley did. Were these men not doing “ranger work” either?

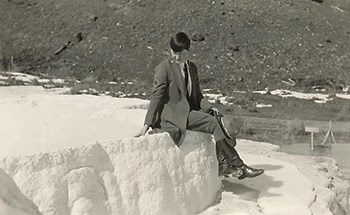

Working in the information office as a permanent ranger, Lindsley also supervised the “90-day wonders” (rangers on summer appointments) doing the same kind of work she herself did. During the winters Lindsley also made observations at geysers and hot springs, read water gauges at rivers, inspected trails, performed fire patrols, conducted systematic animal surveys, and wrote reports—duties that were no doubt also done by men rangers. Yet Albright and others never suggest that these men were anything other than “real rangers.”

Lindsley, for one, seemed to understand what was at stake by publicizing that she did more than “indoor work.” In a November 1927 response to a request to include her in a biographical publication, she urged the writer, “Do not stress the outdoor work too much—many still think that women’s work should be inside, and it is a problem sometimes to satisfy everyone even tho [sic] I may be qualified for the work in the field.”

An Anti-Woman Order

In spite of Albright’s belief that “in certain phases of our education work women can do just as well if not better than men,” women were set to lose the small gains they had made in getting NPS field positions. As rumors spread in 1926 that the NPS was to remove all women park rangers—including those working in the education program—a handful of supporters wrote to the NPS and DOI in protest.

In January 1927, Dr. Conard (who had recently resigned from his park ranger position for unrelated reasons) called for the “anti-woman order” to be delayed for a year in the hope that the “injustice and stupidity of this order may become evident.”

The DOI and NPS responded that “No hard and fast rule has been adopted by the Department of the Interior in regard to the employment of women in the educational work of the National Park Service.” The secretary of the Interior stated that they did not want to hire more women until a designation other than “ranger” could be found because that title “has been, for many years, a term associated with vigorous and courageous men of the West, particularly in the field of strenuous police service.”

The NPS noted that the “high ability of women in this line of activity already has been amply demonstrated in the national parks” but cited that “certain physical conditions” meant that the NPS would “at least for the present, not extend further the opportunities of employment to women.”

The Right Sort of Woman

As he reflected back on his NPS career in his later years, Albright proudly recounted his 1920 vote for passage of the 19th Amendment to the US Constitution and remembered the early women rangers and their accomplishments fondly, leading many to believe that he was a champion for women’s rights in the NPS. Some writers see diplomacy and attempts at reason in his response to the DOI report. The assumption is that he didn’t necessarily mean what he wrote. After all, he was responsible for hiring 10 women rangers at Yellowstone between 1920 and 1928—surely, he must have supported women as park rangers, right?

Other documents refute that assumption and, indeed, suggest that he was not the advocate for women rangers that some might imagine (or, indeed, women clerks—see More than “Just” a Secretary). The minutes of the Ninth National Park Conference held in November 1926 recorded, “The question of the women ranger came up for discussion again.” (Again? Unfortunately we don’t have the minutes for the eighth conference). Albright is quoted as saying, “I am opposed to the woman ranger as such and wish we could call them something else. Women are excellent in information offices and the only way it seems we can get them is to call them rangers. If we get them as clerks we have to get them through the Civil Service Commission, and you don’t always get a person of personality.”

This was Albright speaking to his peers at the conference and expressing his true feelings on the subject at the time, which were in fact consistent with much of what he wrote in response to the DOI report. Of course, Albright was not alone in this position at the time. Unfortunately the minutes do not include any of the discussion that followed, only noting, “Most of the superintendents agreed with Mr. Albright on this.” Wouldn’t it be nice to know who had disagreed with him?

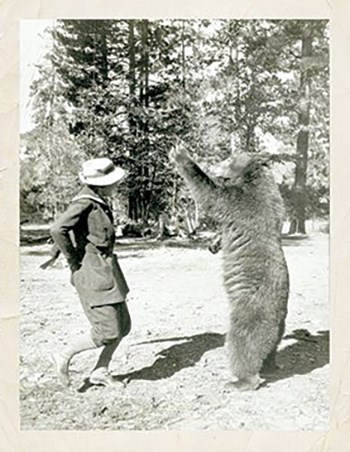

Perhaps the fairest assessment is to say that Albright’s feelings about women rangers were conflicted. He objected to giving them the “ranger” title but he was also the first to put them into the ranger uniform, giving them the “ranger look.” He hired well-educated, competent women but regularly refers to their attactiveness. He hired more women rangers than other superintendents, yet he had definite ideas about the limited roles they should have. He denied that they did “ranger duties” on the one hand but then praised them for doing them well on the other. At the same 1926 conference where he emphatically stated that he was against women being called rangers, in another session he reported that there were advantages to having “the right sort of woman” working for the NPS.

The Door Closes

In spite of past successes hiring the wives and daughters of park rangers—women who by and large were already living in park conditions or in family housing—both the DOI and NPS adopted the argument that “suitable quarters” were not available to women in most parks and hiring them reduced housing options for single men.

Ironically, just as park ranger jobs were closing to women in 1926–1927, at least two magazine profiles and more than half a dozen syndicated newspaper articles featuring Lindsley (and a couple written by her) were printed. Even newspaper stories intended to increase visitation to the park’s museum couldn’t resist sharing Lindsley’s backstory.

As a result of the profiles and articles, Lindsley received many letters from women interested in becoming rangers and seeking career advice in 1926–1927. Her responses dissuaded them from seeking NPS jobs and instead referred them to the concessioners running hotels and camps in the park. She stressed that there were places that women could work in the outdoors, but “it is my belief that the National Park Service is not one of them.”

Lindsley resigned her permanent position in 1928 when she married fellow ranger Ben Arnold. She returned to a temporary ranger position until March 1929. In June of that year she was appointed temporary ranger (naturalist), a position she held until she resigned from the NPS in September 1931.

A few other women rangers rode out the transition period between “park rangers” and “ranger-naturalists.” Wisdom and Pound returned as “park rangers (checker)” for the 1928 and 1929 seasons (see What Did You Call Me?). Wisdom briefly reclaimed the park ranger title for her last season in 1930. Ruby H. Anderson, a telephone operator at Yellowstone in 1927 and 1928, worked a single month in 1928 as a park ranger (checker), before working several short-term appointments as a clerk at the park in 1929.

At Yosemite, Eva McNally and Martha Bingaman kept their park ranger titles through their last seasons in 1927 and 1928, respectively. Enid Michael was the only woman ranger rehired after 1929. From 1928 to 1942, her title was park ranger (naturalist). With the changes to Civil Service regulations, other women sought the new ranger-naturalist positions as well. Most found that men quickly excluded them from those jobs as well.

A handful of women were hired under the park ranger title in the 1930s in the Southwestern Monuments, and at least one worked at Carlsbad Caverns National Park. During World War II women rangers were once again hired in a few parks, temporarily filling positions left by men fighting in the war.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.