Last updated: December 10, 2024

Article

A New Species of Fungus Discovered at World's End

A glimpse at the newly discovered species of fungus quietly thriving on a peninsula of the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park & perspective from the park fungi junkie who studies it.

By Elle Bernbaum, Biological Technician

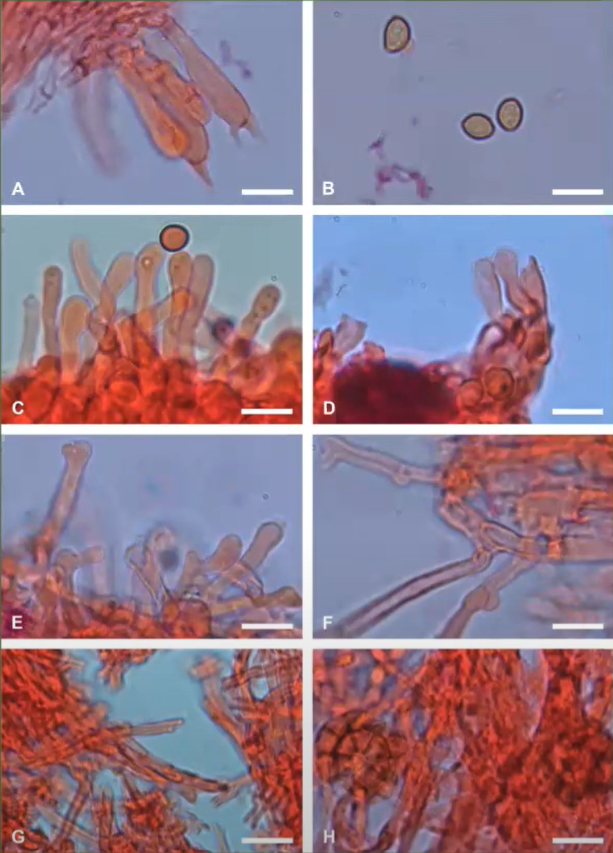

L. Mortier et al.

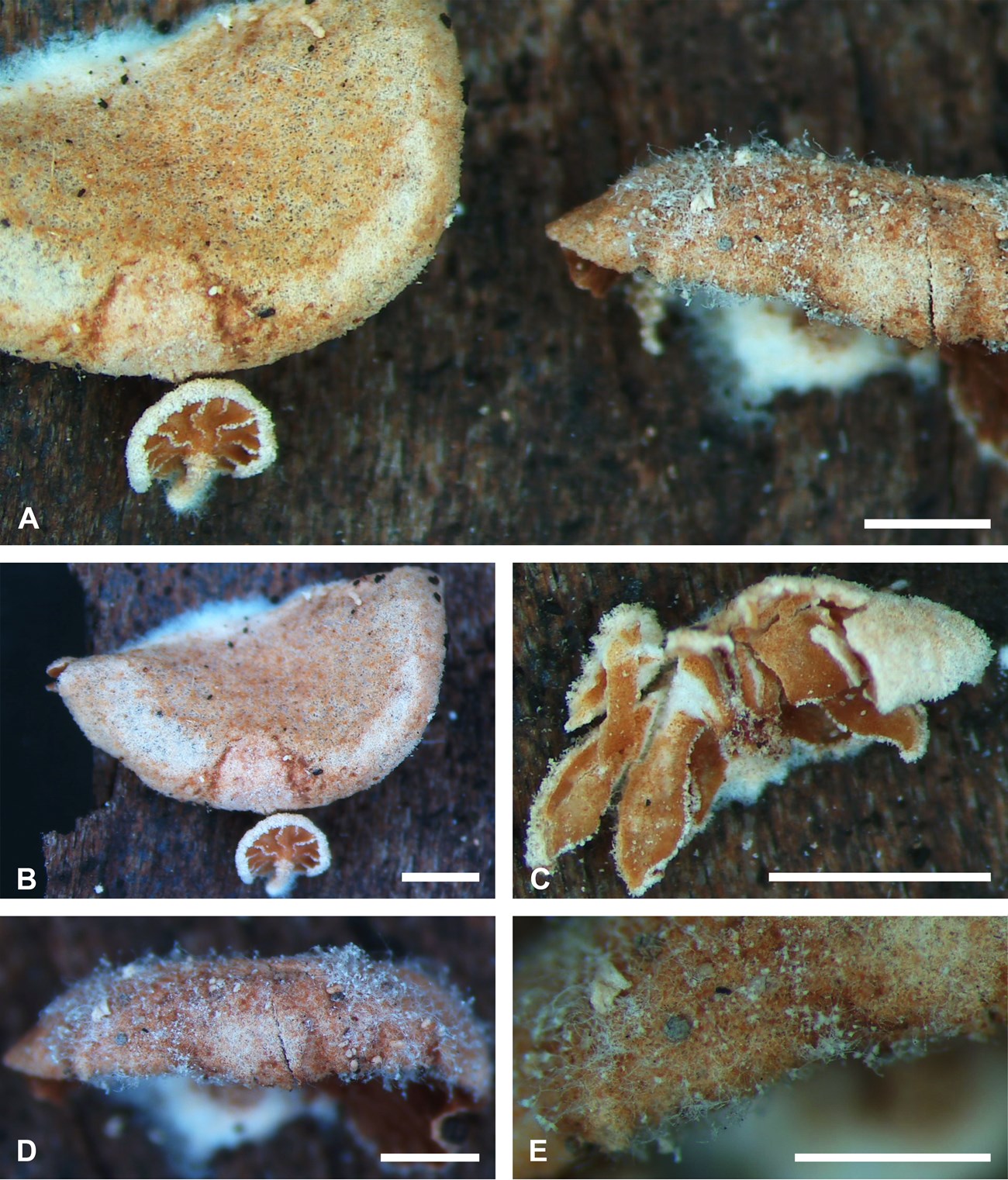

Simocybe ramosa.

That’s the never-before-recorded species of fungus discovered by mycologists here in the Boston Harbor Islands. In March 2024, Dr. Danny Haelewaters and colleagues published a first-ever scientific paper about the species in the journal Northeastern Naturalist, formally acknowledging its existence in our world.

Simocybe ramosa is a panoply of sienna, russet, and copper browns, with an eccentric stem growing a little askew, not quite into the center of the cap. Like a beleaguered beret, its fuzzy cap sits with a slight droop atop the off-kilter stem, giving a charming nod. But, few spot this hushed performance. At only 55 mm tall, Simocybe ramosa is nearly imperceptible.

The squat little species of fungus joins no less than 245 others documented in our park – a number that changes more often than you might think.

Mycologists have identified an average of 12 additional species of fungi in the Boston Harbor Islands each year since 2018, and there are surely more to come. Thousands more species may live in Boston’s backyard, sprouting from the soils of Grape Island and hiding under oak bark at World’s End – that's what mycologists surmise. Dozens among those are likely new to modern-day human knowledge, having never before been recorded – like Simocybe ramosa.

The Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park and partners are on the hunt for these fungi, seeking to protect them, learn about them, and uncover the answers that they hold – answers to questions about the historied islands that we steward.

Fungi Under the Radar: A Legacy

It's unlikely that these species are new arrivals to the Boston Harbor Islands. The reason why researchers are suddenly discovering so many is simple: for the first time in our park’s history, scientists here are looking for them.

Roo Vandegrift

Fungi like Simocybe ramosa have flourished unnoticed by most of us and unstudied by the overwhelming majority of researchers for as long as western science has sought to document biodiversity.

Even after the conservation movement became prominent in the American public discourse in the mid-1800s, fungi biodiversity went unmentioned.

From the pencil of Henry David Thoreau and the paintbrush of Asher B. Durand to the voice of Duwamish and Squamish Chief Seattle, cries for conservation and preservation rang through the 1850s. Outcry turned to policy at the turn of the century as conservationist John Muir, preservationist Gifford Pinchot, and then-president Teddy Roosevelt lobbied for protections. But while appreciation for birds, reptiles, mammals, fish, tall trees, and deep basins grew, appreciation for fungi did not.

Danny Haelewaters

These and other famous thought-leaders, authors, artists, and policymakers waged war to defend the American wilderness, but their focus was set on bigger creatures and more arresting places, like the bison of Yellowstone and the scenic valleys of Yosemite.

Just two fungi species are listed under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) established in 1973, alongside 673 animals and 881 plants. Traditionally, these nutrient-bolstering and often ecologically beneficial organisms haven’t been relevant enough in our majority culture to earn protection.

Now, over a century and a half later, momentum has begun to shift.

Scientists like Harvard entomologist Edward O. Wilson put fungi on center stage in the early 2000s, reminding us to pay attention to "the little things that run the world."

The wilderness of ordinary vision may have vanished – wolf, puma and wolverine no longer exist in the tamed forests of Massachusetts. But another, even more ancient wilderness lives on.

Danny Haelewaters

It’s still rare to find a national park doing fungal inventory work. But, in 2012, inspired by Wilson’s message, that’s exactly what the Boston Habor Islands National and State Park began. It became the park's vision to document the hundreds – perhaps thousands – of species of overlooked fungi on our islands and peninsulas.

And from 2012 to 2019, it was Dr. Danny Haelewaters’ job to find them.

Lara Kappler

On the Hunt

Danny Haelewaters is a Belgian mycologist with an infectious enthusiasm for fungi discovery and research – something that became clear in an interview with him.

"It looks pretty cool, huh?" he gleefully inquired when first sharing his team’s now formally accepted academic paper describing Simocybe ramosa on World’s End. The very mention of his paper summoned a wide grin to his face.

For Haelewaters’, the best part of the job of a mycologist is the excitement of sharing knowledge with other budding mycologists and working with them to move the field further. Sipping from his beetle-hanger-fungus-illustrated mug, he’d talk about his research like it was his baby.

-

It takes a village (Haelewaters)

Audio clip sampled from an interview with mycologist Dr. Danny Haelewaters and NPS science communicator Elle Bernbaum.

Haelewaters spearheaded the inventory program here at the Boston Harbor Islands. At the time, a Harvard PhD student, he spent years on the hunt for new species not yet known.

He’d leave the university in the early mornings, drive and boat with teams of students, sometimes friends, and family to one of the islands nearby or maybe the peninsula of World’s End and return to his lab by midday to begin processing his team’s finds. Then back out into the field by the afternoon. Sometimes, he wouldn’t finish processing until midnight. It’s easy to collect fifty specimens in a day, he remarked, but it’s also important to process all of those fungi in that same day.

Lara Kappler

This act of processing was the real limiting factor that determined how much Haelewaters and his team could collect during the fungi inventory project. Fungi need to be measured and characterized within a few hours if they’re to be documented properly.

-

Processing fungi (Haelewaters)

Audio clip sampled from an interview with mycologist Dr. Danny Haelewaters and NPS science communicator Elle Bernbaum.

When Haelewaters was out in the field, collecting specimens, he’d have a basket, a book of color grids that he’d use to pinpoint fungi colors with exactitude, and of course, a field notebook to record smells... and tastes... a little less exactly.

-

You hold it by your nose... (Haelewaters)

Audio clip sampled from an interview with mycologist Dr. Danny Haelewaters and NPS science communicator Elle Bernbaum.

It was through this process of finding, smelling, tasting, and processing that Haelewaters first documented Simocybe ramosa – one of the fungi that put World’s End on the mycological map.

A Rare New Species Found

Halewaters found Simocybe ramosa shyly growing under the bark of a lone oak tree at World’s End. He got to name it – he and his team. That rush still hasn’t worn off, even after over a decade of naming and discovering.

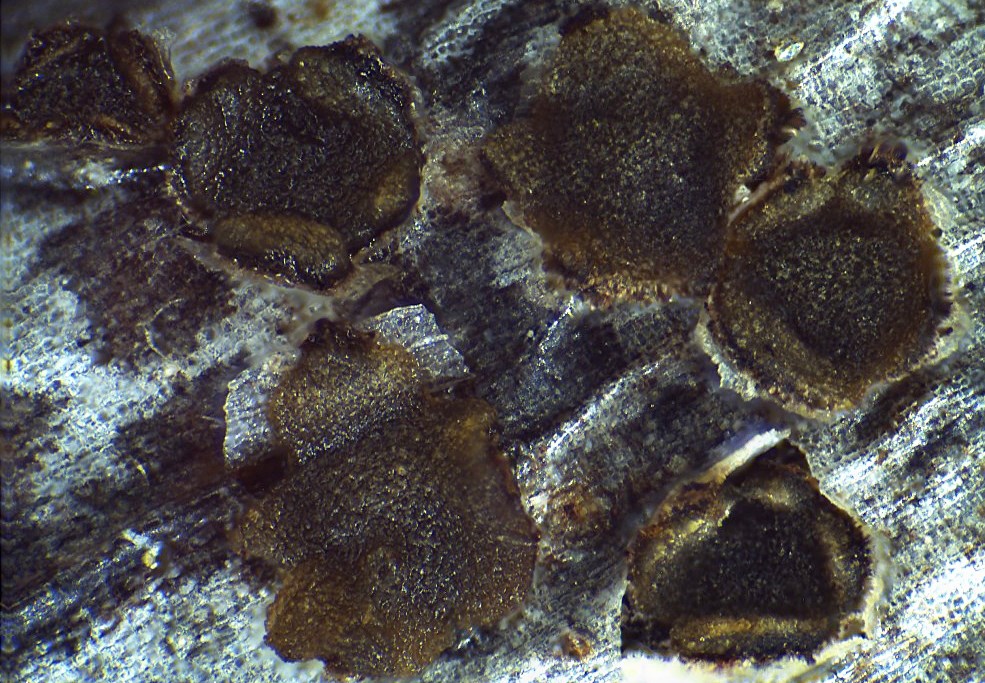

L. Mortier et al.

He’s looked for the species in other places and other times. (The more specimens, the better their description.) But Haelewaters only ever found that one specimen that one time hiding beneath oak bark at World’s End.

It’s been years since his team first collected that single specimen. It was one of many in his collector’s basket, sampled during one of many a field excursion. He had no idea what he was carrying with him – not until its genes had been sequenced much later in the lab. That sequencing and processing can take a lot of time.

NPS Photo

Haelewaters and his team collected nearly 1000 specimens from the Boston Harbor Islands by the end of the field portion of the inventory effort five years ago, and they’re still sequencing those specimens today.

-

Barcodes in the Genome (Haelewaters)

Audio clip sampled from an interview with mycologist Dr. Danny Haelewaters and NPS science communicator Elle Bernbaum.

L. Mortier et al.

Because it’s a new species only found once in one spot on the Boston Harbor Islands, Simocybe ramosa will likely earn a special conservation status – it'll be placed on a red list. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) maintains this Red List of Threatened Species, which catalogues species that require conservation status.

Red listing rare species is one of the important impacts of the work that Haelewaters does. Knowing that Simocybe ramosa exists and that it’s rare can guide park managers to make more informed, protective decisions about the conservation of the oak forest habitat where the simocybe prefers to grow.

Through inventory work, the park and its partners are better able to take measures to protect all native species – not just plants, not just animals, but simocybe ramosa too. In the process, park land stewards support a healthier, more abundant ecosystem.

Of course, having a checklist of the fungal species growing on our islands and peninsulas helps us ask new questions too. Haelewaters has a lot of questions he’d like to answer.

What fungi can tell us about the islands

Haelewaters has been away from the fungi of the Boston Harbor Islands in recent years. He’s been teaching in universities across Europe and building inventories across the globe. But he plans to return soon, and when he comes back, he hopes to collect soil samples from Boston Harbor’s islands and peninsulas.

NPS Photo/ E. Bernbaum

Using soil, Haelewaters can characterize conditions in the ecosystem that he can’t see. He’ll get a glimpse at factors that might be affecting these fungi. It's possible – maybe even likely – that human disturbance and climate change have impacted the growth of fungi and continue to affect their biodiversity.

Haelewaters suspects this. He’s done informal research already, using samples he already collected for the inventory. He compared the number of species on smaller islands like Grape to the number on larger islands like Peddocks and Thompson (also known as Cathleen Stone) Islands. Then, he compared all of those counts to species counts on World’s End on the mainland.

There’s a key principle in biogeography studies, a field that looks at the distribution of species: there are generally fewer species on smaller islands and on islands further from the mainland. It’s more challenging for organisms to travel to those places. Smaller, more remote locations also tend to have less diverse habitats that offer fewer opportunities for organisms to make their homes.

Guided by this well-documented principle, you’d expect that a smaller island, like Grape, would have fewer species than a larger island like Peddocks. That’s not what Haelewaters found, though. Peddocks had the fewest species of fungi.

This tells us that there’s likely some other factor affecting fungal growth in the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park.

Danny Haelewaters

Of course, Haelewaters will be the first to mention that this informal research is not rigorous enough to offer conclusive evidence that something unexplained is affecting the fledging fungi of Peddocks. It is enough, however, to make him want conclusive evidence – and explanations.

Haelewaters hopes to do more research on the outer harbor islands too – they're not as protected from harsh environmental conditions as Thompson/Cathleen Stone or Grape Islands. They’re windier, further from the mainland, and have fewer plant and insect species that fungi may use as homes. These factors make it challenging for spores to reach those islands and establish themselves – it's that same principle of island biogeography at work. At least, that’s what Haelewaters assumes about the outer harbor islands. The fungi there haven’t been studied – he’d like to have a look for himself.

By studying the outer Harbor Islands now, before storms become even more intense and frequent under climate change, Haelewaters and park stewards can get a better sense of how changes to the islands will impact island fungi. As climate change puts more stress on the outer island habitats, they may become even less hospitable than they already are. Rare fungi that enjoy a woody caress from the underside of elm bark may no longer find elms on the changing outer harbor islands as life for these trees gets harder there.

We just don’t know yet. And that’s why we need baseline data. There’s so much research and inventory work that lies ahead. Based on soil and environmental data, Haelewaters estimates that there could be 6 million species of fungi out there, and we only know about 2.5% of them.

Fungi finders are playing a game of catch-up, facing a seemingly infinite sea of unseen, unexplored knowledge, of which, we’ve only skimmed the surface.

-

Mycology today (Haelewaters)

Audio clip sampled from an interview with mycologist Dr. Danny Haelewaters and NPS science communicator Elle Bernbaum.

That might be the biggest reason why Danny is a mycologist working at the Boston Harbor Islands.

Danny Haelewaters

Many Thanks

To Dr. Danny Haelewaters for his time, knowledge, and lasting dedication.

Learn More:

The Atlantic: Give Fungi the Respect They're Due, by J. Moens & Undark