Part of a series of articles titled Stories of Massachusetts Conservation .

Article

American Conservation in the Twentieth Century

By: Ann E. Chapman

At the national level, environmental historians have identified three major historic strands of conservation thinking and action that have provided historic foundations for the contemporary environmental movement. These are utilitarian conservation (natural resource management), preservationist conservation (preserving scenic nature), and wildlife habitat protection. While utilitarian and preservationist arguments dominated the 19th century open space conservation initiatives, wildlife habitat protection has increasingly become a motivation for protection of open space in the 20th century.

Practices in the 19th century and increasingly sophisticated ecological studies in the 20th century resulted in initiatives to preserve ecological habitat throughout the 20th century. Early federal, state, and private initiatives to preserve forests begun during the 19th century continued into the 20th century. Many of the protected open spaces that we have today—and to a large extent, the arguments that we still use to conserve and protect natural places for their scenic, recreational, or habitat values—have been inherited from one or more of these three traditions.

Another trend has been and continues to be the growing appreciation of the need to recognize and protect historic landscapes as part of the nation's heritage, as evidenced by the heightened interest in listing them in the National Register of Historic Places. Many are included in the National Register already.

Federal Role in Progressive Era Forest Conservation Initiatives

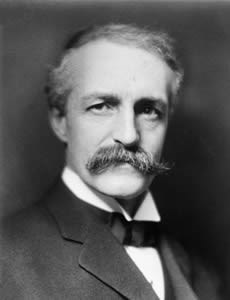

Gifford Pinchot, chief forester during Theodore Roosevelt’s administration, promoted use of the term “Conservation” and lobbied for support for sustained-yield management principles and the creation of a national forest system managed by those principles. He and Roosevelt also lobbied against exploitation of the nation’s soils and minerals, arguing that unregulated private exploitation threatened the nation’s long-term security. Reflecting his utilitarian conservation principles, Pinchot lobbied for the transfer of the federal forest reserves from oversight of the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture, accomplished in 1905, using the rationale that forests should be managed as a crop, with the goal of continued sustained yield (cut no more timber than you replace). The Forest Service’s doctrine of timber management established a foundation for 20th century resource management principles of the U.S. Forest Service. Resources were managed for multiple uses, including timber, wildlife, recreation, range and water. Some US Forest Service sustained yield policies such as issuance of grazing permits on forested land; cutting of old growth forests; and failure to establish adequate habitat protection for some endangered species have been controversial with conservationists concerned with habitat protection (Merchant, 2002; Penick, 2001).

Progressive Era Conservationists and Preservationists Split: Conflict over the Hetch Hetchy Dam

In the 19th century, supporters of utilitarian conservation and preservationist initiatives often worked together on initiatives like National Forest conservation and watershed protection. Over time, however, differences in philosophy created tensions between preservationists like John Muir, who favored the preservation of scenic wilderness areas, and conservationists like Gifford Pinchot, who believed that natural resources were meant to be used. The tensions came to a head in 1909 with a proposal to dam the Tuolumne River in Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park, in order to create a water supply for the city of San Francisco. Gifford Pinchot favored damming the Valley, and John Muir and other preservationists were fiercely opposed. Ultimately, the dam was approved, and Hetch Hetchy became a reservoir in 1913.

Creation of the National Park Service

Support for a new federal agency to protect national parks led in 1916 to the establishment of the National Park Service. The Service was established to manage the existing national parks, monuments, and reservations that had by that time been set aside for natural, scenic, and historic values and to provide for their enjoyment so as to leave them unimpaired for future generations. The number of national parks grew to more than 350 by the end of the 20th century. Debates over preservation of wilderness areas versus development of natural resources for timber or water--and the split between utilitarian and preservationist points of view—have continued in some form throughout the 20th century, and, at the federal level, are reflected in very different management objectives of the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service. These differing values also influenced state and local initiatives to save forests (as timber or parkland) in a number of states in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The Federal Role in 20th Century Habitat Protection

While many states passed legislation designed to protect migratory birds in the last years of the 19th century, there was growing awareness that, because of the vast distances birds traveled during migration, effective protection of migratory birds would require national and international protection. Increasingly, Audubon societies, sportsmen’s organizations, and other supporters for bird protection lobbied for a strong role for the Federal Government in habitat protection.

In 1900, the Lacey Act became the first federal legislation outlawing interstate shipment of birds killed in violation of state laws. In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt established the first Federal wildlife refuge for the protection of waterfowl, Pelican Island in Florida. By the end of Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, over 50 additional refuges had been established. In 1913, the signing of the Migratory Bird Treaty gave the Federal government primary jurisdiction over migratory birds, superseding state laws. With this law, the Federal Government became the primary protector of waterfowl.

The 1920s saw important scientific studies by Frederick Lincoln, a U.S. Biological Service scientist, who used bird banding to identify the major migratory bird flyways in North and South America. He identified four major flyways passing across portions of the United States. This knowledge would become extremely important in later efforts to protect key migratory bird habitat in the U.S.

Despite protective efforts, waterfowl population continued to decline in the 1930s driving some species toward extinction. By 1934, there were only 150 egrets left, and 14 whooping cranes. In 1934, President Franklin Roosevelt created a commission to study wildlife restoration. Conservationist and cartoonist “Ding” Darling and Aldo Leopold were two of the members. Darling later received an appointment to head the Bureau of Biological Survey. Industrialization and urbanization, with loss of wetlands habitat, were seen as major contributors to the loss of bird habitat. In some cases, federal projects for other agencies contributed to the loss of wetlands. The Civilian Conservation Corps, for example, which worked on many conservation-related projects in the Depression era, was involved in flood control and wetlands drainage programs in order to create new agricultural lands. The conflict in federal policies led to the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act of 1934.

The establishment of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1940, merged the Bureau of Fisheries (Department of Commerce) and the Bureau of Biological Survey (Department of Agriculture). The new Fish and Wildlife Service became a unit of the Department of the Interior with a mandate to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, and their habitats. The Service oversees national wildlife refuges and fish hatcheries, and develops recovery plans for endangered species.

The National Wildlife Refuge System has grown dramatically since 1903, since the establishment of the first National Wildlife Refuge on Pelican Island, Florida. There are now more than 530 refuges in the National Wildlife Refuge System, administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, providing 93 million acres of lands and waters managed for the protection of wildlife and habitat. The U.S. National Wildlife Refuge System is the most comprehensive wildlife management system in the world.

Additional Conservation and Planning Issues in the 20th Century

Issues of increasing concern in the 20th century included suburbanization and fragmentation of wild areas through road building, patterns of development that we now call “sprawl.” New tools for city and regional planning were developed in the first half of the century, including zoning. Benton MacKaye’s 1921 article proposing an Appalachian Trail was an initiative that envisioned not only a recreational trail, but also an intact belt of wilderness along the Appalachian Ridge that could contain eastern urban populations. The ambitious idea of trails, to be built and maintained by volunteers, was one example of 20th century initiatives, which were increasingly regional in scope, and often involved complex collaborative efforts. Open space initiatives such as state forest preservation initiatives in many states were popular with the public, but could result in disagreements over the extent of appropriate development—how easy should access to wilderness areas be? Should lodges, ski trails, and other amenities be added or did they interfere with scenic amenities or habitat?

In 1935, Aldo Leopold, Benton MacKaye, Robert Mitchell and others with concerns about the growing network of highways leading to previously inaccessible locations, founded the Wilderness Society. The Wilderness Society lobbied for passage of the Federal Wilderness Act (1964), which established the National Wilderness Preservation System. This system now has more than 95 million acres of protected land. The Nature Conservancy, founded in 1951, was organized with the goal of protecting habitat and acquired more than 1500 preserves and over 9 million acres in North America.

Legacies of 1960s and 1970s Environmental Movement

In the second half of the 20th century, public concerns increased over a wide range of environmental issues, many related to quality of life. In urban areas, the toxic effects of polluted air and water were growing concerns. In suburban areas, a host of issues arose, including the loss of scenic and rural character, habitat fragmentation, and the spread of harmful pesticides and other chemical pollutants. Existing conservation organizations cultivated larger memberships and new groups formed, too. Grassroots organizations often began with local issues and later broadened in their concerns. They helped to educate the public and lobbied for legislation that would address a wide range of environmental issues. Local grassroots advocacy groups formed in both urban and suburban areas throughout the country, working on a variety of environmental concerns in their own area. Grassroots efforts coalesced in into a social movement in 1970, with the holding of the first Earth Day. Communities all over the country engaged in environmental activities.

Two influential books in environmental thinking in the mid-20th century were Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, and Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, published in 1948. The compellingly written Silent Spring drew public attention to the alarming toxic effects of DDT and some other common pesticides on both wildlife and on people. In Sand County Almanac, Aldo Leopold demonstrated through work on his own property the restoration of badly eroded land created healthy wildlife habitat. The science of ecology provided new understandings of requirements for wildlife habitat, and the dangers of habitat fragmentation. A third book, Thoreau’s Walden, became an instant classic with many environmentalists, who used it to illustrate a healthier ideal for people living in harmony with nature.

Growth of the science of ecology led to an increased understanding of the requirements for wildlife habitat and the dangers of habitat fragmentation. Ecological arguments were persuasively in support of both local open space preservation initiatives and for wilderness preservation of large tracts of land. Growing public support for environmental protection in the 1960s and 1970s, led to the passage of much new federal legislation, including the Clean Air Act (1963); the Wilderness Act (1964); the Water Quality Control Act (1965); the Wild and Scenic River Act (1968); the National Trails System Act (1968); the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA, 1969); and the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970). The loss of historic and cultural resources in communities throughout the nation, sparked the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (1966).

Grassroots environmental and open space initiatives dramatically expanded in the second half of the 20th century. Watershed associations, local and regional land trusts, and local conservation commissions continue to work to protect scenic, recreational or ecological resources, often in partnership with other organizations and with state and federal agencies.

Increasingly, protected open space has become an important component in community and regional planning initiatives with a wide array of benefits. While 19th and early 20th century initiatives to preserve open space generally focused on a specific argument (utilitarian conservation, scenic preservation, or habitat protection), contemporary initiatives increasingly recognize that open space serves multiple uses. The contemporary greenway movement is one example. Greenways create linear linkages between open spaces, and provide a combination of recreational, ecological, and/or cultural amenities.

The listing of an increasing number of historic American landscapes and properties associated with conservation in communities throughout the nation in the National Register of Historic Places reflects the growing appreciation of their importance to history, health, and quality of life in the United States. The destinations featured in this travel itinerary that are included in the National Register because of their significance to the nation's heritage are evidence of this trend.

Last updated: July 7, 2020