Last updated: January 26, 2023

Article

Modern Women of Capitol Reef

Throughout the human history of Capitol Reef National Park, women have played a role.

Native people have utilized this area for thousands of years, and continue to have ties to the park. From approximately 300 to 1300 CE, the Fremont Culture (Hisatsinom - people who lived long ago), lived in what is now Capitol Reef National Park and the surrounding areas. Men likely hunted and brought home game while the women tended the farms, made clothing and tools, and tended to the next generation. Without the whole community contributing, the Hisatsinom would not have been as successful and thrived for nearly 1,000 years. People who followed them include the Ute, Paiute, Navajo, and other native groups.

Ellen Powell Thompson explored alongside her husband and others as they mapped this area in 1871. Pioneer families started to arrive in the late 1800's, developing the community of Fruita. Later residents included artists, businesswomen, and National Park Service staff.

Cora Oyler Smith

Cora was the longest resident Fruita ever had. She grew up as the youngest of three sisters, attended the Fruita Grade School and spent her free time listening to the gramophone, playing piano, riding horses, and helping her father in the orchard. Her life was marked by tragedy early on. Her older sister Clara died of typhoid at age 8. A few years later, her oldest sister Carrie’s appendix burst and she died as well, leaving Cora as her parent’s only surviving child.

Cora married Merin Smith at 19. They bought land from her father and planted more orchards; Cora planted many of the trees herself. She was one of the only residents of Fruita who was against the area becoming a national monument in 1937. She foresaw how much the community might change. Cora adopted and fostered several children over the years. She had recently built a new home- with green trim and picture windows- when it was decided Highway 24 would be constructed on her land. She went to court and fought the decision, but ultimately she lost the fight to eminent domain. Her home was condemned, and the highway was built in 1962. Cora said she hadn’t wanted things to change. “I thought I would keep it like it was forever."

Elizabeth Russell Lewis Sprang King

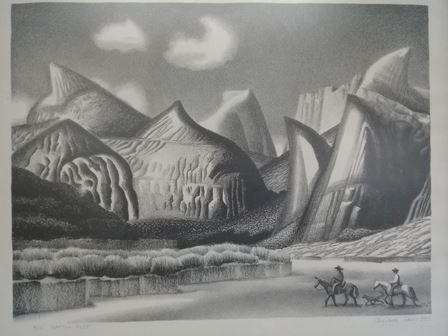

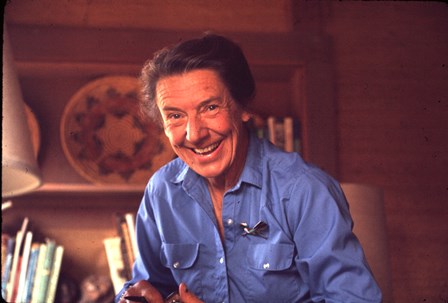

Elizabeth was an artist. She and her first husband moved to Fruita for his health. A few years after they moved to Fruita, Elizabeth’s husband died and she became a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. She later married Dick Sprang, a widower and Batman comic book artist who was living in Fruita at the time. Elizabeth loved the red Utah rocks and was frequently inspired by them as she explored Capitol Reef, Glen Canyon, and the surrounding area. She participated in efforts to save Glen Canyon from being dammed, and wrote the book Goodbye, River in homage to the place Glen Canyon once was. Elizabeth used the landscape and history here to inspire her work. She painted and sketched landscapes (using oils, watercolors, and crayons), and created lithographs, emphasizing texture in her portrayal of cliffs and rockscapes. She also constructed large bas-relief works based on prehistoric petroglyphs and pictographs she encountered in the area. Dick Sprang said in a letter to park interpreter Davidson, that Elizabeth was “a far better and noted artist than I ever was.”

She became a member of the Relief Society and taught Sunday School.

Elizabeth’s work has been displayed at LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), in galleries in San Francisco, and at the Heard Museum in Phoenix (she was the only non-native person to have artwork displayed there in her lifetime.)

Harriette Greener Kelly

Harriette was married to Charles Kelly, the first park employee, custodian, and superintendent of Capitol Reef. She moved to Fruita from Salt Lake City, and remained there for 20 years. Although she was unpaid, she did a lot of the work to run the park. A family friend said: “Kelly seems to love Fruita, but his wife is beginning to get choked up about it. It seems that Kelly goes traveling around the country taking pictures, etc., and his wife is doing most of the work around the place. She practically never sees anyone to talk to, and it is pretty hard on her.” Though Harriette may have struggled with isolation and being overworked, she did become friends with some of the local women- it seems she would get together with Lila Brimhall and Cora Oyler Smith frequently.

From National Parks and the Woman’s Voice: A History by Polly Welts: “By making homes in remote areas, wives brought stability to parks. They filled the role of helpmate, offering information, first aid, meals, and comfort to visitors and staff and served as centers of communication.”

It’s likely that Harriette was a major factor as to why Charles Kelly became custodian. Southwestern monuments at the time were looking for men who were married to act as custodians, recognizing the vital role that park wives played. Frank (Boss) Pinkley, administrator to southwestern monuments in the 1930’s, referred to park wives as “Honorary Custodians Without Pay.” He included park wives in the first conference for southwestern monument custodians, thanking them and saying their attendance was “well earned by the excellent service… donated by [their] field work.”

NPS photo - Charles Ellett

Alice Knee

Alice was working as a nurse to provide healthcare on the Navajo Reservation when she met Lurton Knee, the owner of the Sleeping Rainbow Ranch at Pleasant Creek. She married Lurt in 1958, and became a partner in the Sleeping Rainbow Ranch business. She would lead tours around Pleasant Creek, the Circle Cliffs, and the southern end of the Waterpocket Fold.

Alice was Capitol Reef’s final resident, moving to a nursing home in Arizona in the mid-nineties (when she was in her 90’s) after the death of her husband Lurt. She and Lurt had sold their property to the park in the 70’s, with the agreement that they could live out their lives in Pleasant Creek- in 1995, Alice quit-claimed her rights to the park.

“Although the guest ranch did not attract large numbers of visitors, it became a favorite of writers, artists, and, especially, photographers who came year after year to enjoy the unique setting. Alice's Arabian horses galloped through green pastures below the mesa. Wild asparagus grew abundantly along irrigation canals. A garden supplied fresh vegetables to guests who ate together and conversed on the lodge's dining porch. A family of foxes visited the kitchen door each evening looking for scraps. The ranch and Lurt's Jeep tours to remote slickrock wonders were featured in magazines like Arizona Highways.” - Utah Valley University website