Last updated: September 29, 2023

Article

Migration on El Camino Real de los Tejas

Humans have moved across Texas for many years. Before Europeans arrived, Indigenous peoples established the trails that would become El Camino Real de los Tejas. Later, Europeans and Americans also entered Texas, leaving behind unique traces of their own migrations.

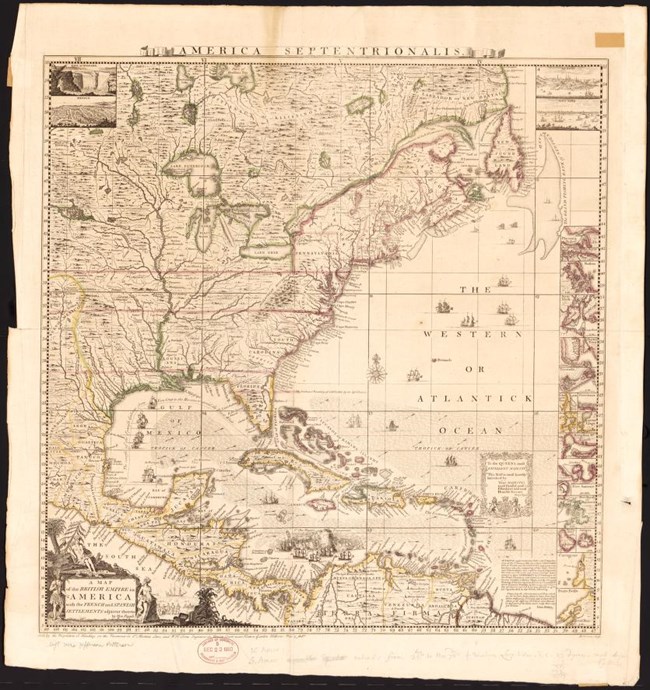

Image/Public Domain

This map of the British Americas from 1733 shows competing European claims in North America, visible in the outlines of French, Spanish, and British territories. Similarly, place names are rendered in English, Spanish, and French. Texas contains mostly the names of Indigenous groups, as it had few Spanish settlements at this time, and the map does not display El Camino Real de los Tejas. Yet despite these absences, the state’s river system—which perhaps affected migration more than any other factor—is well-delineated.

Map Description

A square map in black ink on slightly yellowed paper. Colored lines show political boundaries. The map stretches from northern South America to Canada and from the American Southwest to Newfoundland. The names of different settlements, Indigenous peoples, and geographic features are scattered throughout the map.

Republic of the Rio Grande Museum

River crossings played a major role in migration along the camino. If rivers were running high, travelers would often wait for conditions to improve before crossing; thus, campsites (known as parajes) often sprung up around popular river fords. For expeditions entering Texas, the Rio Grande posed the first major challenge. The two primary crossing points were in Laredo and Eagle Pass, and settlements grew in these areas to supply travelers as they passed through. Later, enslaved people—brought to Texas by their Anglo-American enslavers—would use Eagle Pass to escape into Mexico.

The Stone Fort Museum

Originally built in the eighteenth century, this replica structure in Nacogdoches (designed as a fort but never actually used as one) can teach us a lot about early settlement in northern New Spain. It was built when the Louisiana Territory belonged to Spain, a time of increasing migration from both Spain and France into the area. Technically both a home and a trading post, what came to be known as “The Stone Fort” also served as a government building, a military headquarters, a jail, and even a newspaper office.

The San Antonio River

San Antonio Missions National Historic Park

Like the Rio Grande, the San Antonio River became an important landmark for those traveling the camino. Founded alongside the river of the same name, San Antonio became the capital of Spanish Texas in 1772. In the remote province of Texas, the city relied on migration from outside the area to bolster its population. The same decree that named San Antonio provincial capital announced the abandonment of Los Adaes; its residents were given no choice but to relocate to the new provincial capital (and that with very little notice). Roughly fifty years earlier, the Spanish Crown had approved a plan to move settlers from the Canary Islands to San Antonio. After disembarking at Veracruz and marching overland, they arrived in San Antonio on 9 March 1731. Missions around San Antonio attempted to attract new residents of a different type as efforts to convert Indigenous groups to Catholicism intensified throughout the 1700s.

Nuestra Señora de Rosario Mission

The San Antonio River supported some of the most important settlements in Spanish Texas, but Spaniards did not control the entire watershed. This 1768 letter concerns some “renegade Indians” who stole horses from Presidio La Bahía, located southeast of San Antonio proper in the San Antonio River valley. The thieves were from nearby Nuestra Señora de Rosario Mission, established among the area’s Karankawan peoples to teach them Catholicism and other European practices. The area’s Indigenous inhabitants, however, used the mission as a tool; they migrated seasonally, arriving in the winter (when food was scarce) and departing in the spring (when food was widely available). Yet this strategy did not prevent Spanish missionaries from exploiting. Indigenous labor. Tovar’s letter ends by mentioning that the “renegade Indians” had returned to the mission, and he promises to “punish their boldness with hard works.”

Letter Translation

Enclosed, I sent your lordship the adjoining sealed envelope. My courier brought to this Presidio, by orders of the most excellent seen your history, to be delivered in your large ships hands. I am sending it with a corporal, Joseph, Francisco de Los Santos, and two soldiers, whom, in my opinion, or enough security. He has orders to go by the Presidio of oracle Kiesza, since I have been told your lordship might go through there when returning to San Antonio, or for the visitation to this Presidio.

I also make known to your lordship that on the night of the 19th, and to the 20th of the last month of May the renegade Indians from El Rosario mission, took five horses from this Presidio. Since I was told about it early, I immediately got on my horse, and, accompanied by all the soldiers I could dispose of I followed the trail of those Indians. At a distance about 18 to 20 leagues I met three Indian men and some Indian women that willingly were heading straight to the Presidio, not wanting to go anywhere else. Taking one of the Indians, to serve as a spy, he led me to a settlement where he surrendered the renegade Indians to me. These Indians, having put down their arms, pick them up again after a while, winning a soldier of my division on the head and hurting his arm. The place where this happened was at the outlet of the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers, and was very uncomfortable because of the large red grass, plantations, as well as because of the proximity of the water where they were hidden. I ordered the trip to open fire to punish their boldness, and having one and one Indian he came out of the water and gave himself up. He is completely well now. I could only apprehend three old Indian women in too young ones, as well as the horses they had stolen burning, there can you. I also took away from them one of the two shotguns they had, along with a few 1 ounce, bullets, and a flask, with a small amount of gunpowder.

The Indian that served me as a spy, informed me that all of this had been taken from the Spanish vessel, that more than two months ago had crashed at the port, called Matagorda. Although all or the majority of the people were saved, and stayed with the friendly Cara Chua Indians, on the island of the sad port, and had a banquet of fish being given to them, while eating, they were treacherously, killed and buried in two big ditches, dug by the Indians. The mentioned Indian said that he had seen this place. He also said they took mini shotguns, gun powder, bullets, and new shirts. After having convince this Indian to take me to that place, he said he would; and he did, but he warned me. It was necessary to take plenty of men, since there was a great number of Indians, there, for the foregoing purpose, I made use of an order I issued, and which I am presenting to your lordship. Among the resident, soldiers, and Jara, Naomi Indians, that I requested from the father, minister of the Espíritu Santo mission, I could gather 46 men with you my marched on the morning of the 24th of the said month of May. As they arrived on the 23rd from the other side of the coast. The mentioned Indian took me through trails, hardly used, and then he informed me that it was , necessary to take the canoes away from the Indians, living on the island so we could go into the port. This could not be done any other way, because there is a distance of 3 to 4 leagues from the land to the high seas. Accelerating the march on account of the debit devotion, I always give the royal service of his majesty he took me a very abundant river, whose waters are the color of bricks.

This river, surrounded from north to south by a beautiful mountain, all around the cardinal points, which has beautiful Woods. On the west side, there’s a delightful Lagoon with many Willow and poplar trees; and there is a Valley on the east side, disappearing on the Verizon, and which is about little more than 10 weeks from shore.

On the afternoon of the 28th, I left this place, leaving the horses about five leads behind in custody of 10 citizens. With 36 men, I got across the outlet of this river; for this purpose, I did not stop our march during the night. At quarter before daybreak, I ordered the troop to get in the water, naked, and with their guns to their heads, to get across the river together, with a mentioned, Indian spy to a little island about a quarter of a mile from the shore. They were foot prints, and Having inspected the place only one horse was found. Their camps were still fresh, according to the experts, as the Indians had moved the day before to another island. One of the soldiers was suspicious, and the inspection had not satisfied him; for this reason it was necessary to proceed with a second inspection. I ordered the majority of the soldiers go this time. I started to get undressed, but I could not get into the water due to the insistence of the soldiers, sergeant in corporals, who insisted that since it was so muddy, it was not necessary for me to go, and for me to stay at shore, and wait for them. They went off with most courage, but nothing was found. Such reconnaissance was unsuccessful for lack of a craft. I returned following the coast until I found the outlets of the Guadalupe and San Antonio rivers, because I learned that my career had arrived.

I remain with the most true affection for your lordship, and wishing to receive your orders to for fill them with great promptness.

I remain ad, interim, praying our Lord to keep the life of your lordship many years. Bahia, Del, Espirito Santo, June 6, 1768.

Extra judiciously, I have learned the Indians, who arose in insurrection, after putting down their arms, had returned to the Rosario mission where they belong to. This has been notified to me, and by means of indictment, I will request them to punish their boldness with your hard works.

You’re most affectionate, in constant servitor kisses, your large ships, hand, Francisco de so far

Senior governor Hugo, O’Connor

ALS. 1–4 in E. Six– 6 –1768.

Acequia del Alamo Dam

Acequias are important physical reminders of Spanish migration and settlement. First utilized by the Moorish inhabitants of Spain’s arid regions, acequias helped irrigate crops in the drier parts of New Spain as well (Although New Mexico’s Puebloans and other Indigenous peoples had long practiced their own irrigation methods before the arrival of Spaniards). Although the particular acequia at Mission San Antonio de Valero is no longer active, others in Texas and New Mexico are still used for agriculture.

American Exploration and Migration

One of the best English-language sources on Spanish Texas was written by Zebulon Pike, an American military officer arrested by Spanish authorities and escorted back to the U.S. across what is today northern Mexico and Texas. In this 1810 map, the Rio del Norte is today’s Rio Grande, and San Antonio is clearly indicated just above a doubled dotted line resembling tire tracks. Relations between Spain and the United States were tense during Pike’s time. Spanish forces believed that Pike was the forerunner of a major American invasion. While there is no proof of this, Pike’s published journals—including the above map—provided plenty of Americans with new information about Spanish territories that, in just 38 years, would become the U.S. Southwest.

Map Description

A square map with black ink on yellow paper. The map stretches from northern Mexico to Colorado and from the Gulf of California to the Gulf of Mexico. The Rio Grande runs north to south at the map’s center. Mountain ranges are shown in relief, but otherwise the map lacks topography.

Image/Public Domain

Settling Texas

American migration from the United States started soon after the Louisiana Purchase. The Spanish government and their Mexican successors were not entirely opposed to it. During its final years, the Spanish government began to consider Anglo petitions for land grants, and the Mexican government—recognizing that a more populated Texas would serve as a convenient buffer with the United States, as well as powerful Indigenous groups like the Comanche—continued this policy. This 1822 letter offers a behind-the-scenes look at American efforts to settle Mexican Texas. Colonization laws passed shortly thereafter allowed American agents, called empresarios, to bring large groups of Anglo-Americans to settle Texas on grants authorized by the Mexican government. Many of them brought enslaved African Americans with them, raising an issue that would become one of the underlying causes of the Texas revolution (1835-36).

Fort Boggy State Park

Most Anglo-Americans established themselves on Indigenous land in remote parts of Texas. Settlers in what is now Leon County, in East Texas, made their homes near Kichai and Kickapoo encampments. The establishment of Fort Boggy in 1839 was a direct response to their anxieties about living so close to Indigenous people that they considered hostile. Texas president Mirabeau Lamar, known for essentially expelling Cherokees and Comanches from Texas, authorized a military company to protect the fort. It fell into disrepair as the perceived need to protect settlers diminished.

El Camino Real de los Tejas has seen many waves of migrants pass into Texas and become part of the larger body politic. Though the types of transportation have changed, the large migration of peoples during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have left a permanent mark on the landscape along El Camino Real de los Tejas. While the Rio Grande now acts as a national border, the impacts of centuries of movement along the camino remain.

(Special thanks to UNM PhD candidate Meghann Chavez for compiling this information)