|

The Zion-Mt. Carmel Highway and Tunnel provides direct access for travel between Bryce Canyon, Grand Canyon, and Zion National Parks. Learn more about current tunnel information and hours of operation.

In 1909, President William Howard Taft designated Mukuntuweap National Monument at Zion Canyon using the power granted to him in the 1906 Antiquities Act. The canyon was so remote at this time that it required little protection. However, this also meant that the park lacked the infrastructure needed to support visitation.

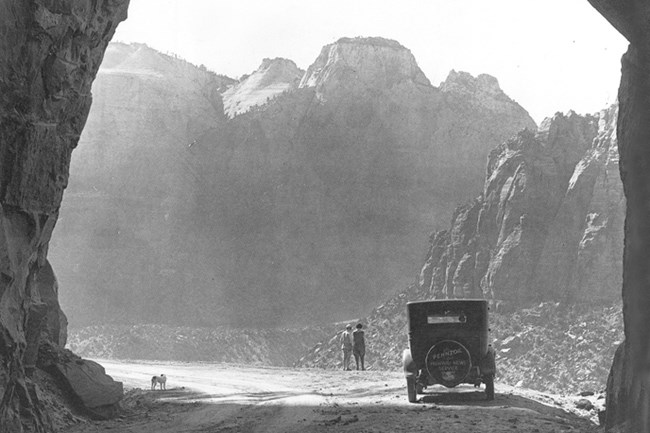

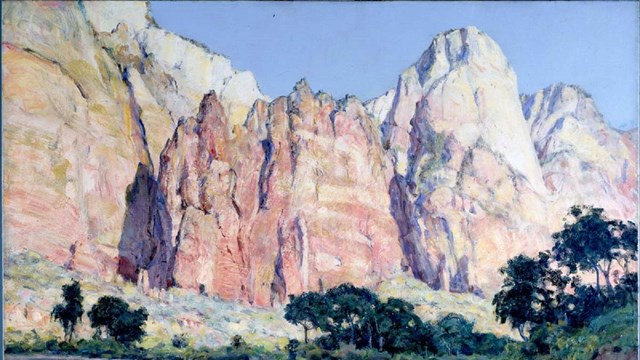

A part of realizing the "Grand Loop" was the construction and completion of the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway and Tunnel. The 25-mile road was a joint effort between the National Park Service, the state of Utah, and the Bureau of Public Roads. A road designed to go where no road had gone before, the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway and Tunnel went up Pine Creek Canyon, through the Navajo sandstone cliffs to the eastern plateau, then across slickrock country.

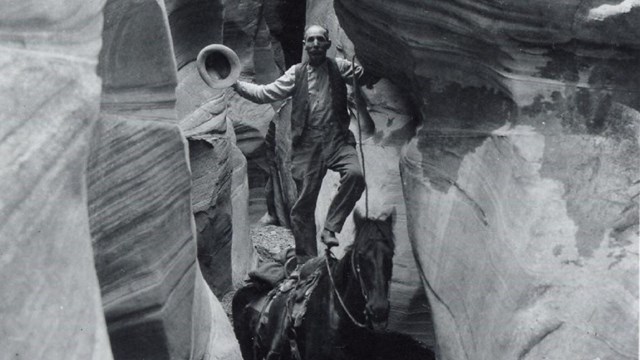

Four different crews from both Utah and Nevada began work on opposite ends of the planned road. On the western side, the Nevada Contracting Company of Fallon, Nevada began carving a series of seven switchbacks from the canyon floor up to the sandstone cliffs above. The soft rock beneath the Navajo sandstone cliffs sloughed away and rockslides were a continuous problem. Large boulders posed a regular threat to workers and had to be blasted into smaller rocks with dynamite to prevent catastrophes. However, accidents did occur. At one point, a rockslide caused a large boulder to roll down over the switchbacks and killed one of the men working below.

Two years and ten months after the project began, the work was completed, and on July 3, 1930, the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway and Tunnel was officially dedicated and opened to the public. Visitors traveled along the new scenic route in the comfort of an automobile and enjoyed views of the high desert landscape along the way. The once imagined "Grand Circle Tour" of Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Grand Canyon National Parks was now a reality.

People

Learn more about the diverse peoples who have called Zion home for thousands of years.

Places

Discover historic places and structures at Zion.

Zion-Mt. Carmel Tunnel Use Information

Get information about driving large vehicles through the Zion-Mt. Carmel Tunnel. |

Last updated: July 8, 2024