Photos by C. Fong Moving water leaves its signature throughout Yosemite. It has shaped the park’s dramatic landscapes, most visibly in Yosemite’s smooth granite and famous waterfalls. The presence of water is also seen in the lush green of Yosemite’s meadows and the groves of giant sequoias that require specific hydrological conditions to thrive. The water that originates here also plays a critical role in satisfying California’s need for fresh water and supports myriad species on its way to the Pacific Ocean.

What is hydrology? Simply put, hydrology is the study of water and its interactions with the landscape. Precipitation falls on Yosemite as rain or snow, some of which immediately runs into lakes and rivers, flowing over Yosemite’s spectacular and through magnificent river canyons. Some is stored in snowpack or groundwater, used by plants and trees, or evaporates back into the atmosphere only to fall elsewhere. The science of hydrology seeks to understand the processes that control how much water flows into our streams, how much is stored underground, how water moves through the landscape, the quality of that water, and the ways that it is recycled in the natural environment. Yosemite National Park’s hydrology program, in cooperation with the US Geological Survey (USGS), the Merced Irrigation District, and Hetch Hetchy Water and Power, monitors water quantity and quality to provide information for drought management, park planning, and long-term hydrologic trends and possible ecological impacts. River gages in Yosemite have been active for many decades, producing valuable long-term records. Data has been recorded at Happy Isles by the USGS for over 100 years! (View real-time flow data at Happy Isles gaging station.) Park scientists also assess water quality along the Merced and Tuolumne Wild and Scenic Rivers, which together drain the entire park. The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act awards special protection to the quality of the water and the free-flowing condition of these rivers, and the park is responsible for upholding these high standards. Yosemite Observer Dashboard: Physical SciencesVisual, interactive information about current weather, stream flow, fires, and air quality conditions; all on one site!

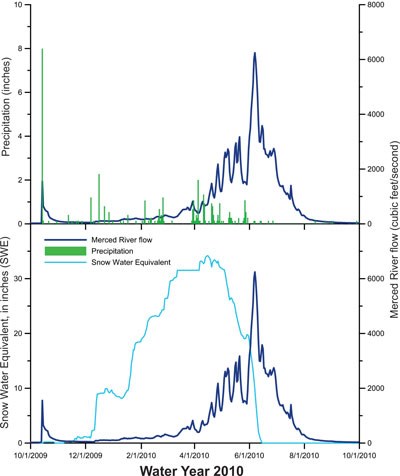

Yosemite's hydrologic resources are fascinating to examine in part because of its Mediterranean climate, which is characterized by cool, wet winters and long, dry summers. This extreme contrast generates some of the most diverse ecosystems on earth due to the adaptations species have made to survive in these conditions. In Yosemite’s case, most precipitation falls as snow that accumulates above 6,000 feet (1,830 meters) during the winter, creating a natural water reservoir. The snowpack slowly releases meltwater through the spring and early summer, nourishing downstream regions well into the dry season. This snowpack is deposited by large storms, which bring tremendous amounts of moisture from the Pacific Ocean into California each winter. As this warm, moist air encounters the Sierra Nevada, it is forced up and over peaks as high as 14,000 feet (4,270 meters). As the air moves up and over the mountains, it cools by several degrees Fahrenheit per 1,000 feet (several degrees Celsius per 1,000 meters), causing water to condense and fall as rain or snow. This process, called the orographic effect, is the primary reason half of California's total water supply originates in the Sierra Nevada. Areas east of the Sierra, like Owens Valley, are drier because this moisture has been "wrung out" as it traverses the range, in an effect called a rain shadow.

Photos by Greg Stock

Local ecosystems take advantage of the hydrologic patterns of winter snowpack and spring snowmelt. As spring temperatures rise, snow begins to melt, saturating soil and filling streams and rivers. This annual rise in water levels is referred to as the "spring pulse." Rising streams and groundwater levels inundate meadows and wetland areas, bringing nutrients and sediments that sustain these biologically rich areas. Plants and animals from the foothills to alpine meadows take advantage of the spring pulse to carry out important aspects of their life cycles, such as amphibians that lay their eggs in flooded meadows.

(Right) Later in spring, snowmelt will temporarily flood meadows, providing a key water influx for plants and animals.

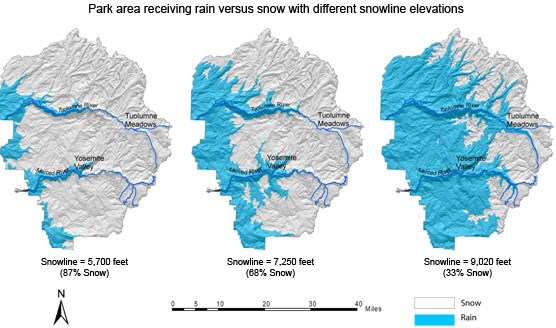

A warming climate will profoundly affect this balance. Currently, the map at left shows Yosemite’s average winter snow line (5,700 feet). However, Northern California is predicted to warm 5-11°F (3-6°C) by the year 2100. With an increase of 11°F, the warmer storm mentioned above with a high snowline (9,020 feet; see above right) is estimated to become the new average, while the center map shows an average snow line for 5°F of warming. This change will lower annual snowpack volume, cause earlier melting, and decrease the size of the spring meltwater pulse, resulting in longer, drier summers with less water in rivers, streams, and aquifers. Learn More:

|

Last updated: August 22, 2023