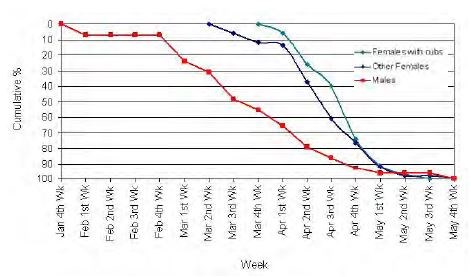

From Yellowstone Science 23(2): 2015, pages 90-95. Farewell to a Friend On April 22, 2015, Dr. Lester Lee Eberhardt passed away at the age of 91. Dr. Eberhardt co-authored numerous peer-reviewed papers while working with former Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team leader Dr. Richard Knight on grizzly bear demographics in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. He also worked closely with National Park Service biologists on predator-prey dynamics and the effects of wolf restoration to the ecosystem. Dr. Eberhardt was world-renowned for his pioneering work on the demographics and population dynamics of grizzly bears, marine mammals, ungulates, wolves, and other long-lived vertebrates. Like grizzly bears, he was a survivor of large-scale change, including the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, World War II, and political battles over grizzly bear conservation and habitat protection. Dr. Eberhardt was a mentor to many biologists working in the Yellowstone area, and he will be sincerely missed by all his friends and colleagues in the world of ecology and wildlife management. Two Grizzly Bear Patriarchs With Long Study History Pass on in 2014 Mark A. Haroldson & Frank T. van Manen The grizzly bear research conducted in Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding ecosystem is one of the longest ongoing studies of a large carnivore in the world. The study team began capturing and radio-collaring individual bears in 1975, and the effort has continued annually through the present.As a result of the long duration of the study, researchers have developed extensive histories for numerous individual bears. These histories document when and where individuals were captured and the circumstances surrounding those events, when females had offspring and how long the young stayed with their mothers, and ultimately when bears died and the circumstance of their deaths. This past year (2014), the study team documented the death of two male bears with long and fascinating histories. Their passing is of note because both were originally transported into the park after management captures for sheep depredations. Bear #155 was transported to the Blacktail Deer Plateau from the Caribou-Targhee National Forest as a 3-year-old bear in September 1989. He continued to reside in the park after his release and was radio-monitored in 10 of the next 26 years, during which he traveled in the northern or center portions of the park.During the fall of 2014, at the old age of 28, he was captured and euthanized after breaking into an out-building and obtaining food rewards at a residence north of the park. The age of this bear was close to the oldest recorded age in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which was a 31-year-old male. Bear #281 was transported to Yellowstone National Park after being captured for killing sheep near Pinedale, Wyoming, in 1996 at the age of four.Like bear #155, #281 continued to reside within the center portion of the park and was radio-monitored during 11 of the next 18 years. During early June 2014, bear #281 was observed in poor condition near Mud Volcano.Park staff and visitors watched the 22-year-old male bed down under a tree on June 3. On the morning of June 4, he was found dead in the same bed. Upon examination, park staff observed several deep wounds on his shoulders and back near the spine that were likely caused by a fight with another bear. These wounds likely contributed to his poor condition and death. Both bears came to the park under similar circumstances, and both had a long life without much in the way of additional conflicts with humans. There are few places left in the world where large carnivores do that, but Yellowstone National Park is one of those places. Leucistic Elk Observed in Yellowstone Sarah Haas In May 2015, hikers in Yellowstone's northern range encountered a rare sighting.A cow elk with a white coat was observed in a small herd foraging along a hillside. The cow elk, full grown and apparently healthy, was likely leucistic—a form of coat irregularity caused by a lack of melanin production due to a rare recessive genetic trait. Unlike a true albino, where a complete lack of melanin pigment exists, leucism results in a washed-out appearance but does allow for some coat coloration.It is rare to encounter wildlife with either leucism or albinism, as those individuals are generally removed from the population—they are usually easy prey for predators. However, some populations of leucistic animals can survive quite well when afforded conservation protection, passing on their recessive trait to multiple generations, such as the famous white lions of Timbavati in South Africa. The rare sighting of this leucistic cow elk in Yellowstone demonstrates genetic mutation can and does occur world-wide, even in protected areas like a national park. The hikers who watched this unique individual reported that the leucistic elk seemed to be more vigilant than the rest of the herd, apparently noticing the hikers before the other elk in the group. She also tended to stay in the center of the herd, a behavior possibly learned over time to protect herself from predators due to her more obvious appearance. These sightings are of value to park managers and can be early alerts to the health of park wildlife. Please inform a park ranger if you notice odd behavior or appearance of any wildlife in the park—citizen science is a valuable tool for a 2.2 million acre management area! Record High Number of Female Grizzly Bears with Cubs in 2013 Mark A. Haroldson &Frank T. van Manen The Interagency Grizzly Bear Study Team, composed of grizzly bear managers and researchers from both state and federal agencies within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, is responsible for monitoring grizzly bear population trend. One method used by the study team to monitor trend is to track numbers of unique females with cubs-of-the-year (i.e., cubs) observed annually. Females with cubs represent the important reproductive segment of the population. Females produce cubs on average about every three years, so a three-year sum approximates the number of breeding or reproductive females in the population. To accomplish the count, team members compile sightings of females with cubs from annual survey flights and ground-based observations. Next, a "rule set," based primarily on distances between sighting and numbers of cubs in the family, is applied to produce a conservative estimate for the number of unique females with cubs observed. Results vary annually, but there has been a positive trend for the ecosystem since the mid-1980s, with a general leveling off starting in the early 2000s. However, results for 2013 were the highest count to-date, with an estimate of 58 unique females with cubs. For comparison, 49 unique females were identified in 2012 and 50 unique females observed in 2014. The three-year sum from 2012 to 2014 resulted in a total of 157 adult female grizzly bears living in the GYE. The record number of female grizzly bear sightings and the unique families derived from them were well-distributed throughout the ecosystem in 2013, with 15 females with cubs observed within Yellowstone National Park. The long-term average for females with cubs for Yellowstone National Park is 11, with high counts occurring in 1986 (n = 20), 2000 (n = 20), 2004 (n = 22), and 2010 (n = 20). Some Bears Emerge from Dens Early in 2015 Kerry A.Gunther Data from radio-collared bears indicate a small proportion of Yellowstone bears emerge from their dens in early February (figure 1). However, the first observed bear activity of the year is typically not reported until the first week of March, after many adult male bears have emerged from dens to feed on winter-killed ungulate carcasses and succulent emerging spring vegetation. This past winter some bears were observed out of their dens several weeks earlier than what is typical.The winter of 2014-2015 was unseasonably warm with above average temperatures and below average snowfall at elevations under 8,700 feet. At elevations under 7,350 feet, spring snowpack was well below average, due to extremely warm temperatures from mid-March through April. On January 25, a black bear was observed in the Bridger Mountains north of Yellowstone National Park;and on January 27th, grizzly bear tracks were observed near Pahaska Teepee, Wyoming, east of the park. On February 1st, a bear track was observed in the Beattie Gulch drainage, just north of the park boundary at Reese Creek. The first bear activity observed in Yellowstone National Park was a grizzly bear scavenging a bison carcass near Mud Volcano on February 9th. Over the next several days, this bear was observed by park visitors traveling by snowmobile and snow-coach through the park. Although a few bears emerged from dens earlier than typical (possibly because of warm temperatures, melting snow, or availability of food), many bears remained in their dens and emerged at dates more typical for their species, sex, and age class.

Westslope Cutthroat Trout and Artic Grayling Restored to Grayling Creek –Part I Erik Öberg With the tip of a bucket, eight years of planning and preparation delivered hundreds of native trout to their new home. In April, 2015, staff from Yellowstone Center for Resources and Montana State University worked together to capture, transport, and release 680 westslope cutthroat trout (WCT;Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi) from Geode Creek on Yellowstone's Blacktail Plateau to Grayling Creek near West Yellowstone. Initiated in 2007, this project required many elements to result in a successful outcome. Genetics Labs, Inc. in Idaho and Montana helped Yellowstone fisheries biologists identify a 100% genetically pure population of WCT in Geode Creek. Grayling Creek, with over 30 miles of connected tributaries was ideal habitat, had predatory, non-native brown trout (Salmo trutta) and hybridizing rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that needed to be removed for successful WCT reintroduction. Drainages were mapped, an environmental assessment was approved, non-native trout were removed with piscicides, and a fish barrier waterfall was modified to prevent the return of unwanted species. Moving fish is not easy. A team of biologists combed through pools and pocket water of Geode Creek, using backpack mounted electro-shockers to net all 680 fish, one or two fish at a time. Steep terrain and the need to keep fish cool and oxygenated required many arduous trips to transport fish in coolers fitted with aerators to downstream holding cages. Once the target number was captured and counted, the fish were ready for the trip to Grayling Creek. The WCT were placed in a large transport tank and driven to six release sites along Grayling Creek. Snow was added to the tank to keep the water temperature as low as possible to reduce stress on the fish. With less than 4% mortality and rapid dispersal upon release, the WCT appear to be off to an excellent start in their new habitat. Now begins the work of monitoring to determine if long-term success of the project can be achieved. WCT and Artic grayling (Thymallus arcticus) eggs were brought to the Grayling Creek drainage later in the summer of 2015 to restore its namesake fish. Especially for graylings, eggs incubated on-site imprint and acclimate more successfully than fish released from lakes or hatcheries. If the project succeeds, this will be the only fluvial (or river) grayling population in Yellowstone and one of only a handful in the lower 48 states. The first phase of this restoration project is now complete. Review of"Large Carnivore Conservation: Integrating Science and Policy in the North American West" Editors: Clark, S.G., and M. Rutherford. 2014. Large Carnivore Conservation: Integrating Science and Policy in the North American West. University of Chicgo Press, Chicago, IL, USA. Reviewed by: Nathaniel R. Bowersock "Creating a sustainable future depends on changing or adjusting currently unsustainable perspectives and damaging practices to be more realistic and adaptive. This is one function of sound decision making." One of the biggest struggles a wildlife biologist faces is trying to communicate with the public about the scientific research conducted to inform sound management decisions.However, understanding the values of local people when formulating these decisions plays an even bigger role in whether or not these decisions are supported once implemented.In Large Carnivores Conservation: Integrating Science and Policy in the North American West, six case studies are presented that discuss the successes and failures of wildlife biologists trying to conserve large carnivores in North America while balancing the needs of the local communities.As stated in the book, "good science is important for wildlife management, [but] the best science cannot resolve value-based disputes." Not only can wildlife be unpredictable and challenging to manage, but incorporating the human dimension component into conservation efforts can result in obstacles toward success.Some of the case studies presented in the book highlight the challenges of being an effective wildlife manager today.In the case of trying to rehabilitate mountain lions in the American Southwest, local politics were used to undermine the management set forth by wildlife biologists. Biologists tried to use science to prove why their management decisions were positive for both mountain lions and the public;but local fears and concerns outweighed science-based information, and poor mountain lion management was implemented.In another case, biologists trying to manage grizzly bears in the Yukon of Canada found the bear population was in a decline and that new management actions were necessary.However, local people did not like the way biologists were conducting their research because the local people felt the methods were disrespectful to their values. This led to a lack of local support of the research findings and management choices being promoted. On the other hand, in the cases of managing wolves in southern Alberta and grizzly bears in central Montana, wildlife biologists were more successful in communicating their ideas and assessing the values of the local people, which resulted in positive management of large carnivores. Both communities in these cases relied on livestock for a living and were concerned about the expansion of large carnivores into their communities. In both cases, the biologists reached out and involved the local ranchers in the management decisions from the beginning. Both projects also established goals that reduced carnivore-livestock interactions and had flexible management plans that could be adjusted due to dynamic circumstances.These two stories highlighted the importance of how integrating the values of the local community with sound management decisions can provide the public with regulations that most people can accept in order for carnivore populations to prosper. This book is a great resource for wildlife biologists working to conserve large carnivores or any other species of conservation concern. Science is an important tool that should be used to make sound management decisions;but without the consideration of local views or values of wildlife, proper management generally is not successful. The case studies presented in this book provide helpful insight into the many factors biologists need to consider when making management decisions. Additionally, this book is a wonderful way for the public to understand how and why wildlife biologists make daily decisions in their various fields working with a wide spectrum of species.The book's main message is that the management of carnivores will vary with local community values;but with proper communication, an understanding about management choices can be achieved that will allow people and wildlife to coexist. Review of "Protecting Yellowstone - Science and the Politics of National Park Management" Yochim, M.J. 2013. Protecting Yellowstone - Science and the Politics of National Park Management. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, NM, USA. Reviewed by: Sarah Haas For national parks such as Yellowstone, with a complex history, large size, and public popularity, the spotlight on decision making and resource management actions can often be intense.There have been several large-scale and long-lasting debates throughout the park's history that have resulted in not only internal policy making, but had ripple effects throughout the National Park Service. In his book, Protecting Yellowstone - Science and the Politics of National Park Management, Michael Yochim takes a closer look at several of the park's major controversies since the 1980s.The issues range from conflicts over development planning to predator reintroduction.The author selected six major topics to illustrate that even in the same park, during the same era of NPS policy, the outcomes of management decision making can be framed, constrained, and shaped by public values, stakeholder interests, politics, and a variety of pressures on park managers that sometimes have a limited connection with the actual problem being addressed. The book admirably synthesizes six controversies into abbreviated summaries of key events, turning points, and outcomes.Within the confines of 184 pages, the book cannot present an in-depth analysis or the full spectrum of each controversy.However, the author effectively uses interviews with park staff and extensive reviews of park historical documents to frame issues and present his analyses on why the outcomes of these controversies varied widely and which forces were most influential.In the end, the author suggests that the success, or failure, of the park's ability to implement desired management actions hinges on two determinants: politics and the scientific research backing the decision making.Central to this is the ability of park managers to form supportive coalitions with external stakeholders. Yellowstone will continue to face challenges in natural and cultural resource protection, public visitation and safety, budgetary constraints, among other issues.The park is still wrestling with some of the issues presented in Protecting Yellowstone, with bison management the most notable continuing challenge.The author recommends three main strategies for successful policy-making: commitment to scientific research, allowing for sufficient time to build coalitions and resolve differences, and advancing strong visions toward preservation.Park leaders have undoubtedly utilized these, and other, strategies over the years, at times more successfully than others.Yochim's book shines a light on a few of the key challenges faced in the park's recent past with a message to learn from history in order to continue the mission of protecting Yellowstone. |

Last updated: December 21, 2015