US Forest Service, Gardiner Ranger District A mid-size carnivore in the weasel family, the wolverine (Gulo gulo) is active throughout the year in cold, snowy environments to which it is well adapted. Its circumpolar distribution extends south to mountainous areas of the western United States, including the greater Yellowstone area where they use high-elevation islands of boreal (forest) and alpine (tundra) habitat. Wolverines have low reproductive rates, and their ability to disperse among these islands is critical to the population’s viability. Climate-change models predict that by 2050, the spring snowpack needed for wolverine denning and hunting will be limited to portions of the southern Rocky Mountains, the Sierra Nevada range, and greater Yellowstone, of which only the latter currently has a population. Wolverines are so rarely seen and inhabit such remote terrain at low densities that assessing population trends is difficult and sudden declines could go unnoticed for years.

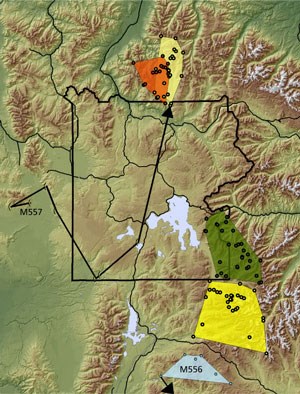

NPS PopulationCommercial trapping and predator control efforts substantially reduced wolverine distribution in the lower 48 states by the 1930s. Some population recovery has occurred, but the species has not been documented recently in major portions of its historic range. In the Greater Yellowstone Area, wolverines have been studied using live traps, telemetry, and aerial surveys. A group sponsored by the Wildlife Conservation Society has documented ranges that extend into Yellowstone National Park along the northwest and southwest boundary. A second group, which included researchers from the National Park Service, the US Forest Service, and the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative, which surveyed the eastern part of the park and adjoin- ing national forest from 2006 to 2009, documented seven wolverines. The average annual range for the two monitored females was 172 mi2 (447 km2); for three males, 350 mi2 (908 km2). The other two males, both originally captured by the Wildlife Conservation Society, dispersed from west and south of the park: M557 established a home range north of the park in 2009; M556 became the first confirmed wolverine in Colorado in 90 years. Conservation StatusWolverine populations in the US Rockies are likely to be genetically interdependent. Even at full capacity, wolverine habitat in the Yellowstone area would support too few females to maintain viability without genetic exchange with peripheral populations. The rugged terrain that comprises a single wolverine home range often overlaps several land management jurisdictions. Collaborative conservation strategies developed across multiple states and jurisdictions are therefore necessary for the persistence of wolverines in the continental United States. In 2013, USFWS proposed the wolverine be listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, only to reverse course the following year. Conservation groups challenged that reversal, and a judge found that the federal government failed to follow the best available science in its decision to not list the animals as threatened. In 2020, USFWS determined that federal protections were not warranted. In 2021, parties identified a potential settlement agreement and a judge remanded the 2020 decision to not list, so status reverts to 2013 proposed threatened status with 18 months to finalize listing status. Climate change impacts on wolverine habitat, specifically the likelihood of declining habitat in high elevation snowpack for denning females, had been identified as a chief threat to this species. In Montana, which has the largest wolverine population of the lower 48 states, an annual quota of 5 wolverines were available for harvest by licensed trappers in recent years.

Marten

Member of the weasel family that lives in woodlands.

Long-tailed Weasel

Long-tailed weasels change color based on the season.

Mammals

All of the park's hoofed mammals migrate across the park to find the best plant growth. ResourcesAubry, K.B., K.S. McKelvey, and J.P. Copeland. 2007. Distribution and broadscale habitat relations of the wolverine in the contiguous United States. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(7):2147–2158. Copeland, J.P., J.M. Peek, C.R. Groves, W.E. Melquist, K.S. McKelvey, G.W. McDaniel, C.D. Long, and C.E. Harris. 2007. Seasonal habitat associations of the wolverine in central Idaho. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(7):2201–2212. Inman, R.M., R.R. Wigglesworth, K.H. Inman, M.K. Schwartz, B.L. Brock, and J.D. Rieck. 2004. Wolverine makes extensive movements in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem. Northwest Science 78(3):261–266. Krebs, J., E. Lofroth, J. Copeland, V. Banci, D. Cooley, H. Golden, A. Magoun, R. Mulders, and B. Shults. 2004. Synthesis of survival rates and causes of mortality in North American wolverines. Journal of Wildlife Management 68(3):493–502. Murphy, S.C., and M.M. Meagher. 2000. The status of wolverines, lynx, and fishers in Yellowstone National Park. In A.P. Curlee, A. Gillesberg and D. Casey, ed., Greater Yellowstone predators: Ecology and conservation in a changing landscape, 57–62. Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative and Yellowstone National Park. Murphy, K., J. Wilmot, J. Copeland, D. Tyers, and J. Squires. 2011. Wolverines in Greater Yellowstone. Yellowstone Science 19(3): 17–24. Robinson, B. and S. Gehman. 1998. Searching for “skunk bears”: The elusive wolverine. Yellowstone Science 6(3): 2–5. Ruggiero, L.F., K.S. McKelvey, K.B. Aubry, J.P. Copeland, D.H. Pletscher, and M.G. Hornocker. 2007. Wolverine conservation and management. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(7):2145–2146. Squires, J.R., J.P. Copeland, T.J. Ulizio, M.K. Schwartz, and L.F. Ruggiero. 2007. Sources and patterns of wolverine mortality in western Montana. Journal of Wildlife Management 71(7):2213–2220. Ulizio, T.J., J.R. Squires, D.H. Pletscher, M.K. Schwartz, J.J. Claar, and L.F. Ruggiero. 2006. The efficacy of obtaining genetic-based identifications from putative wolverine snow tracks. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(5):1326–1332. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (2014) Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Threatened Status for the Distinct Population Segment of the North American Wolverine Occurring in the Contiguous United States; Establishment of a Nonessential Experimental Population of the North American Wolverine in Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico Federal Register, 79,47522–47545. |