NPS/Diane Renkin

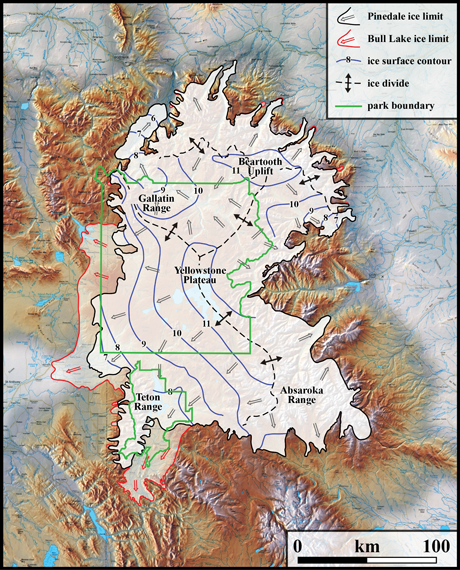

Modified by J. Licciardi in December 2015 from Licciardi and Pierce (2008) Glaciers result when, for a period of years, more snow falls in an area than melts. Once the snow reaches a certain depth, it turns into ice and begins to move under the force of gravity or the pressure of its own weight. During this movement, rocks are picked up and carried in the ice, and these rocks grind Earth’s surface. Ice and water erode and transport earth materials as well as rocks and sediments. Glaciers also deposit materials. Large U-shaped valleys, ridges of debris (moraines), and out-of-place boulders (erratics) are evidence of a glacier’s passing. Yellowstone and much of North America have experienced numerous periods of glaciation during the last 2.6 million years. Succeeding periods of glaciation have destroyed most surface evidence of previous glacial periods, but scientists have found evidence of them in sediment cores taken on land and in the ocean. In Yellowstone, a glacial deposit near Tower Fall dates back 1.3 million years. Evidence of such ancient glaciers is rare. The Bull Lake glaciers covered the region about 151,000 to 160,000 years ago. Evidence exists that this glacial episode extended farther south and west of Yellowstone than the subsequent Pinedale Glaciation, but little surface evidence of it is found to the north and east. This indicates that the Pinedale Glaciation covered or eroded surface evidence of Bull Lake Glaciation in these areas. The Yellowstone region’s last major glaciation, the Pinedale, is the most studied. Its beginning has been hard to pin down because field evidence is missing or inconclusive and dating techniques are inadequate. Ages of Pinedale maximum vary around the Yellowstone Ice Cap from 21,000 years ago on the east to 20,000 years ago on the north and possibly as young as 15,000–16,000 years ago on the south. Most of the Yellowstone Plateau was ice free between 13,000 to 14,000 years ago. During the Pinedale glaciation, glaciers advanced and retreated from the Beartooth Plateau, altering the present-day northern range and other grassy landscapes. During glacial retreat, water flowed differently over Hayden Valley and deposited various sediments. Glacial dams also backed up water over Lamar Valley; when the dams lifted, catastrophic floods helped to form the modern landscape around the North Entrance of the park. During the Pinedale’s peak, nearly all of Yellowstone was covered by an ice cap up to 4,000 feet thick. Mount Washburn was completely covered by ice. This ice cap was not part of the continental ice sheet extending south from Canada. The ice cap occurred here, in part, because Yellowstone’s higher elevation volcanic plateau allowed snow to accumulate.

NPS

More Information References Liccardi, J.M., and Pierce, K.L. 2008. Cosmogenic exposure-age chronologies of Pinedale and Bull Lake glaciations in greater Yellowstone and the Teton Range, USA. Quaternary Science Reviews 27: 817–831. Pierce, K.L. 1979. History and dynamics of glaciation in the Northern Yellowstone National Park Area. US Geological Survey Professional Paper 729–F. Pierce, K.L. 2004. Pleistocene glaciations of the Rocky Mountains in Developments in Quaternary Science, J. Rose (ed). 1: 63–76. Elsevier Press. |

Last updated: April 18, 2025