Park Highlights

NPS/Jim Peaco Old FaithfulOld Faithful Geyser is, perhaps, the most famous geyser in the world. As the name suggests, the eruptions are rather predictable, with the standard interval being 94 minutes ± 10 minutes. The geyser averages an eruption of 130 feet (40 m), lasting 11/2–5 minutes, and expelling 3,700–8,400 gallons (14,000–31,800 L) of water. At the vent, water temperatures have been recorded at 203°F (95.6°C), which is above the boiling point of water at this elevation. This is not the only hydrothermal feature to see in the area. In fact, Old Faithful is just one of hundreds of hydrothermal features in the area known as the Upper Geyser Basin. There are 150 geysers—4 more predictable ones—within one square mile, plus hundreds of hot springs. An extensive trail and boardwalk system provides up-close views of many of these features, and connects to nearby Black Sand Basin and Biscuit Basin.

NPS/Jim Peaco Grand Prismatic SpringSix miles north of the Old Faithful area is a small, but spectacular, hydrothermal basin known as Midway Geyser Basin. This is the home of Grand Prismatic Spring, Yellowstone's largest hot spring and one of the most colorful features on earth. Grand Prismatic Spring is 200–330 feet (61–100 m) in diameter and more than 121 feet (36.8 m) deep. The wide variety of colors comes from thermophiles, organisms that live in high-temperature environments. Each band of color is a different collection of thermophiles. Some thermophiles have specific ranges of temperatures they can live in, so the colors also represent different ranges of water temperature. Excelsior Geyser Crater is the other major feature in the area. Once an active geyser, Excelsior Geyser blew itself up and now is a 200 x 300 foot (61 x 91.4 m) hot spring sitting in a crater. It discharges an impressive amount of water—more than 4,000 gallons (15,142 L) of water per minute.

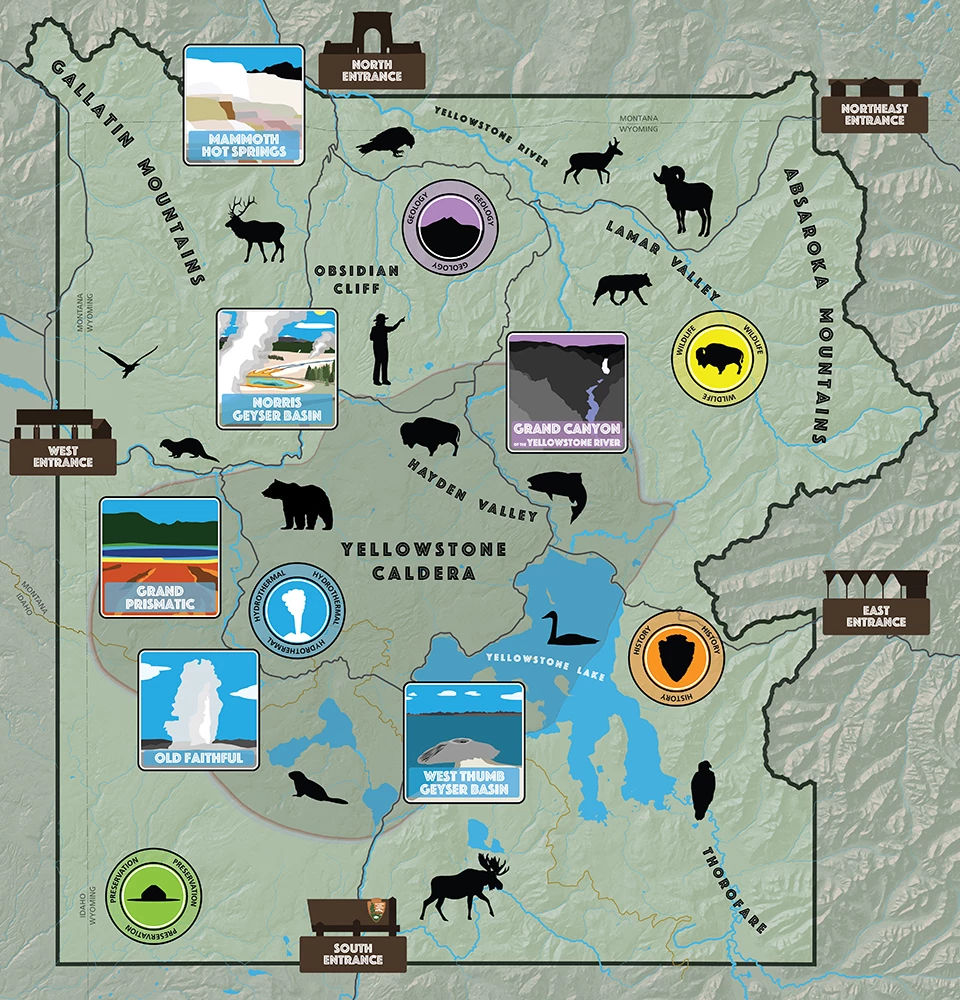

NPS/Dave Krueger Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone RiverThis huge canyon is roughly 20 miles (32 km) long, more than 1,000 feet (305 m) deep, and 1,500–4,000 feet (457–1,219 m) wide at various points. Scientists continue to develop theories about its formation. After the Yellowstone Caldera eruption, about 630,000 years ago, lava flows and volcanic tuffs buried this area. Hydrothermal gases and hot water weakened the rock. The river eroded this rock, carving a canyon from Tower Fall all the way to the Lower Falls. The canyon itself has different colors. The reds are caused by oxidation of iron compounds in the rhyolite rock that has been hydrothermal altered ("cooked"). The yellows are the result of iron and sulfur in the rock.

NPS Mammoth Hot SpringsIn the northern part of the park, outside of the Yellowstone Caldera, are travertine terraces built by hot springs. These large, gentle hydrothermal features are collectively called the Mammoth Hot Springs. Travertine terraces build here because of the underlying limestone. Hot water dissolves the limestone and deposits the mineral at the surface to form the terraces. Colors in the hot springs, like elsewhere in the park, come from thermophiles living in the hot water. Also in the area is a collection of older buildings that made up Fort Yellowstone, where the US Army was based from 1891 to 1913. Today, the historic structures are the headquarters for the park, as well as home to the Albright Visitor Center.

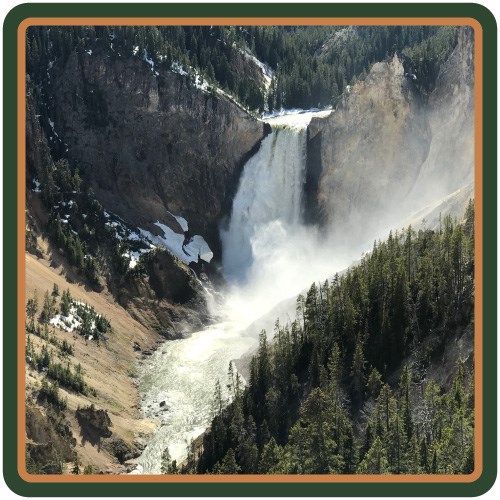

NPS/Curtis Akin Norris Geyser BasinWhile north of the Yellowstone Caldera, it is believed that this geyser basin is connected to the caldera's associated ring of fractures and faults. Norris Geyser Basin, named for Philetus W. Norris (the second superintendent of the park), is considered the hottest geyser basin in the park. Norris Geyser Basin is home to Steamboat Geyser, the tallest active geyser in the world, shooting water and steam more than 300 feet (91 m) into the air during a major eruption. Norris Geyser Basin has many acidic hydrothermal features. Also, all the colors are due to combinations of minerals and thermophiles. Silica or clay minerals saturate acidic water to give them a milky white appearance. Iron oxides, arsenic, and cyanobacteria create red-orange colors. Another thermophile glows bright green. Mats of yet another thermophile appear purple to black when exposed to sun, but bright green beneath. Even sulfur is present to give pale yellow hues.

NPS/Dave Krueger West Thumb Geyser BasinWest Thumb is named because it sticks out of Yellowstone Lake a bit like a thumb sticking out of a hand. The West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake was formed by a volcanic eruption about 174,000 years ago that formed a small caldera. West Thumb Geyser Basin is the largest geyser basin on the shore of Yellowstone Lake—and its hydrothermal features lie under the lake, too. The heat from these features can melt ice on the lake's surface. West Thumb Geyser Basin is home to some interesting hydrothermal features—Fishing Cone (a historic geyser that is only known to have erupted in 1919 and 1939), Black Pool (a hot spring 35–40 feet (11–12 m) deep), West Thumb Paint Pots, and Abyss Pool (a hot spring about 53 feet (16 m) deep). Select Geographic Features

NPS Yellowstone CalderaThe Yellowstone Caldera was created by a massive volcanic eruption about 630,000 years ago. Later lava flows filled in much of the caldera. It is about 30 x 45 miles (48 x 72 km). Both the size and the amount of fill in the caldera make it a challenge to see. The rim can best be seen from the Washburn Hot Springs overlook (south of Dunraven Pass), Gibbon Falls, Lewis Falls, Lake Butte, and Flat Mountain Arm of Yellowstone Lake. During the eruption that formed the Yellowstone Caldera, an estimated 240 miles3 (1,000 km3) of material was ejected from the ground. In comparison, the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens that blew the top and side off the mountain ejected 0.1 miles3 (0.4 km3) of material—less than 0.04% of Yellowstone's last major eruption! The definition of a supervolcano is a volcano capable of eruptions of more than 240 miles3 (1,000 km3) of material, so the last major eruption fits that term. Yellowstone's supervolcano is fueled by a hot spot in the earth's mantle that causes magma to be closer to the surface than normal.

NPS/Jim Peaco Yellowstone LakeYellowstone Lake is natural and has 131.7 square miles (341.1 km2) of surface area and stretches roughly 20 miles (32 km) long by 14 miles (22 km) wide. It also has 141 miles (227 km) of shoreline. At its deepest, it reaches 430 feet (131 m), though it averages a depth of 138 feet (42 m). Overall, the lake's basin has an estimated capacity of 12,095,264 acre–feet (1.5x1013 L) of water! Because the annual outflow of water is about 1,100,000 acre–feet (1.3x1012 L), the lake's water is completely replaces only about every eight to ten years. Since 1952, the annual water level fluctuation has been less than six feet (2 m). It is the largest lake at high elevation (above 7,000 feet / 2,134 m) in North America. The lake's main basin is part of the Yellowstone Caldera, which was formed about 630,000 years ago. West Thumb was formed by a later, smaller eruption. The arms of the lake were formed by uplift along fault lines and sculpting by glaciers.

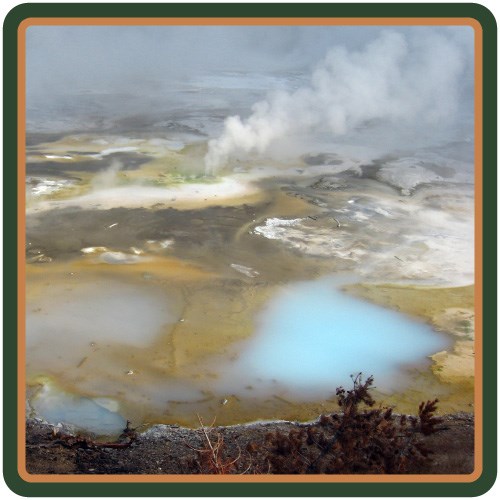

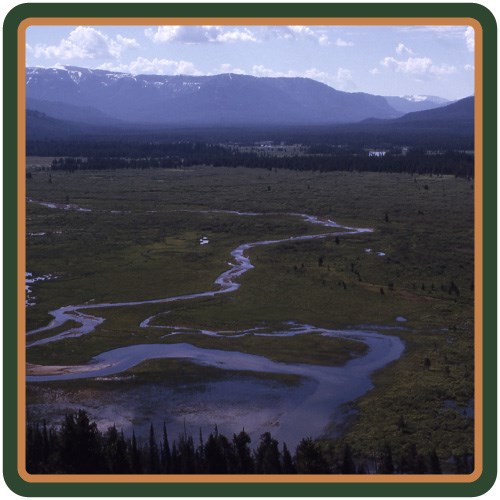

NPS/Dave Krueger Yellowstone RiverWhile the park is named for this river, it actually starts outside of the park on the slopes of Younts Peak in the part of the Absaroka Mountains southeast of the park. The Yellowstone River flows 671 miles (1,080 km) to the Missouri River, near the Montana–North Dakota border. From there, the waters travel to the Mississippi River and on out to the Gulf of America and the Atlantic Ocean. The Yellowstone River is considered the longest undammed river in the contiguous (lower 48) United States of America. The Yellowstone River flow through the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River, dropping down into the canyon via two main waterfalls: Upper Falls and Lower Falls. The Upper Falls drop 109 feet (33 m) and the Lower Falls drop 308 feet (94 m). The flow rate of the Yellowstone River varies seasonally, with a low of 5,000 gallons (18,900 L) per second in the late fall and a high of up to 63,500 gallons (240,000 L) per second at peak runoff in the spring.

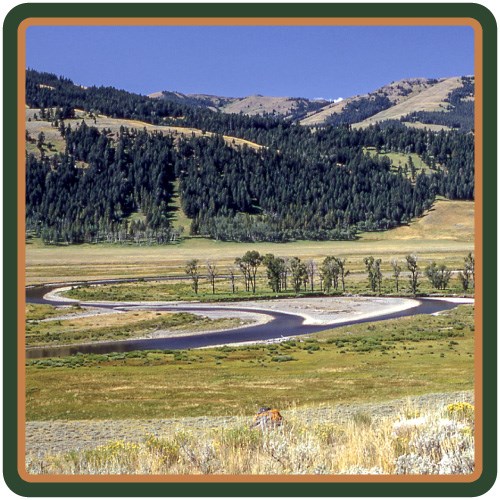

NPS Lamar ValleyLamar Valley is a large, wide-open valley in the northeast part of the park. Glaciers from about 21,000 years ago carved out the Lamar Valley, as well as forming a dam that caused the valley to fill with water. When the dams lifted, catastrophic floods from water released here helped shape the modern landscape around the North Entrance. Today, you can see evidence of the glacial activity in the shape of the valley, as well as huge boulders and ponds left dotting the landscape. The Lamar River flows through the valley in a meandering pattern. Cottonwood trees dot the valley, as due frequent sandbars. Besides the dramatic mountain and valley views, the Lamar Valley is home to the Lamar Buffalo Ranch. The extermination of bison throughout the west in the 1800s nearly eliminated them from Yellowstone. As part of the first effort to preserve a wild species through intensive management, these bison were fed and bred in Lamar Valley at what became known as the Lamar Buffalo Ranch. As the herd grew in size, bison were released to breed with the park’s free-roaming population. Bison from the ranch were also used to start and supplement herds on other public and tribal land.

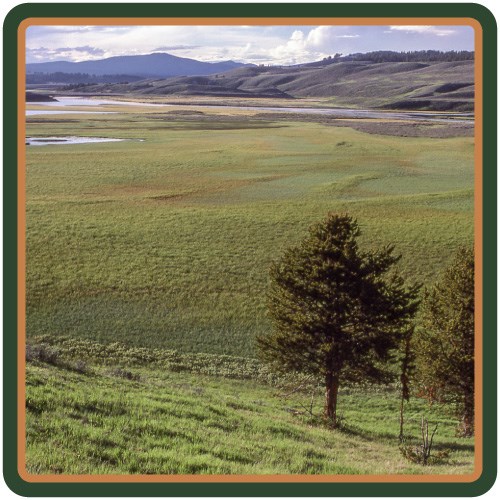

NPS/J. Schmidt Hayden ValleyHayden Valley is covered with glacial till left from the most recent glacial retreat, some 13,000 to 14,000 years ago. The valley also has a variety of glacial and ice-water contact deposits. This glacial till contains many different grain sizes, including clay and a thin layer of lake sediments that do not allow water to percolate quickly into the ground. As a result, Hayden Valley is marshy. Hayden Valley has historically been the major location of the bison rut (mating season), though recent trends have seen the herds move north to the Lamar Valley. Grizzly and black bears are often seen in the spring and early summer. Coyotes and wolves are also seen in the valley. On the south end of Hayden Valley is Mud Volcano, a hydrothermal area rich in features that let off a "rotten egg" smell. This comes from hydrogen sulfide gas. Sulfur, in the form of iron sulfide, gives the features their many shades of gray.

NPS/Jim Peaco Obsidian CliffObsidian is found in volcanic areas where the magma is rich in silica and lava has cooled without forming crystals, creating a black glass that can be honed to an exceptionally thin edge. Unlike most obsidian, which occurs as small rocks strewn amid other formations, Obsidian Cliff has an exposed vertical thickness of about 98 feet (30 m). Obsidian was first quarried from this cliff for tool-making more than 11,000 years ago. In fact, it is the United States' most widely dispersed source of obsidian by hunter-gatherers. It was gradually spread along trade routes from Western Canada to Ohio. Obsidian Cliff is the primary source of obsidian in a large concentration of Midwestern sites, including about 90% of obsidian found in Hopewell mortuary sites in the Ohio River Valley (from about 1,850–1,750 years ago).

NPS/Jim Peaco Gallatin MountainsThe Gallatin Mountains are a mountain range in the northwest part of the park. The highest peak of the range is Electric Peak at 10,969 feet (3,343 m) and sits inside the park boundary near the town of Gardiner, Montana. The range runs about 75 miles (121 km) from Bozeman, Montana down into the park. One of the best views of the Gallatin Mountains is from Swan Lake Flat, a high-elevation valley south of Mammoth Hot Springs. Another panoramic view of the range can be had from the top of Bunsen Peak, the nearby volcano, after a short, but intense, hike of to the top of the peak. The range is also visible from Blacktail Plateau as you head back west toward Mammoth Hot Springs. The Gallatin Mountains inside the park include peaks like Mount Holmes, Dome Mountain, Antler Peak, Quadrant Mountain, Little Quadrant Mount, and Electric Peak.

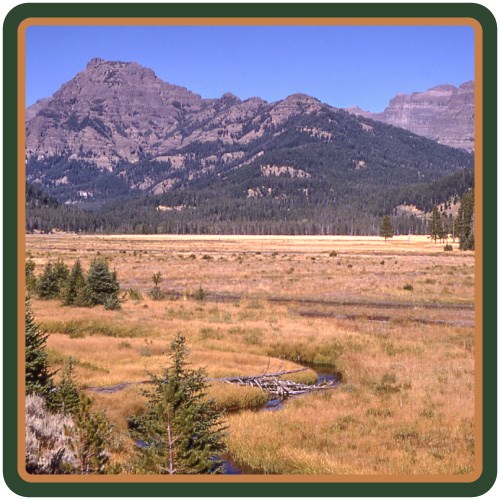

NPS Absaroka MountainsOn the east side of the park, the Absaroka Mountains run all the way from beyond the northern boundary to beyond the southern boundary—some 150 miles (240 km) in all. Some of the most dramatic mountain scenes in the park can be seen in the northeast area, with Barronette Peak, Abiathar Peak, The Thunderer, and Mount Norris all giving daunting views of sheer cliffs and razor-edged ridges. The high point in the park is found in the southern stretch of the Absaroka Mountains‡mdash;Eagle Peak at 11,358 feet (3,462 m). Near Eagle Peak are other prominent mountains, like Table Mountain, Colter Peak, Turret Mountain, Mount Schurz, Mount Stevenson, Mount Doane, and Mount Langford. All of these peaks form the eastern edge of Yellowstone Lake.

NPS/Harlan Kredit ThorofareThe southeast corner of the park is some of the most remote land left in the lower 48 of the United States of America. The Thorofare part of the park is where the Yellowstone River first flows into the park on its way to the Yellowstone River. The Thorofare is also a major migration path for elk moving between the park and lands to the south. The US Army constructed backcountry cabins and snowshoe cabins to provide facilities for troops patrolling for poachers. The Thorofare Patrol Cabin is one such cabin. Built in 1915, the cabin consists of two rooms. The roof extends out 10 feet (3 m) to form a covered porch with a wood deck and support posts at each corner. Park Entrances

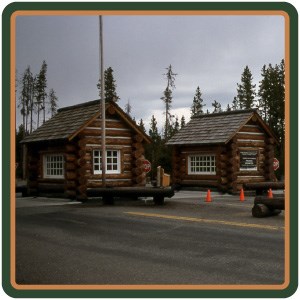

NPS West EntranceThe West Entrance into Yellowstone is the busiest entrance into the park—receiving about as many visitors as the next two entrances (North and South) combined! It is located on the edge of the town of West Yellowstone, Montana. The West Entrance to the park leads you through the Madison Valley, where the Madison River cuts through lava flows as it heads out of the park.

NPS South EntranceThe South Entrance is located nearest Grand Teton National Park and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway. This entrance leads visitors along the Lewis River and past Lewis Lake on the way to the West Thumb of Yellowstone Lake.

NPS/Diane Renkin East EntranceThe East Entrance of the park is accessed by visitors traveling from Cody, Wyoming. Following the Shoshone River, the road beyond the East Entrance climbs up through the Absaroka Mountains to Sylvan Pass, where it then heads down toward the northeastern shore of Yellowstone Lake.

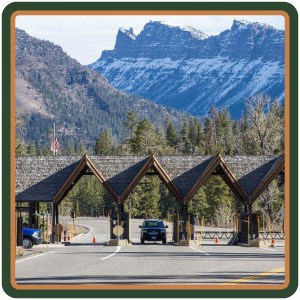

NPS Northeast EntranceThe quietest of Yellowstone's five entrances, the Northeast Entrance is also quite historic. The entrance station was constructed in 1935 in a rustic style emblematic of national park architecture. This architecture “subconsciously reinforced the visitor’s sense of the western frontier... not only the physical boundary, but the psychological boundary between the rest of the world and what was set aside as a permanently wild place.” Visitors entering the park from this direction pass through the steep Absaroka Mountains while following the Soda Butte Creek as it flows down to the Lamar River.

NPS North EntranceLocated near Gardiner, Montana, this is the only entrance that is open year-round. The historic Roosevelt Arch (named after President Theodore Roosevelt, who dedicated the arch by laying the cornerstone in 1903) is 50 feet (15 m) high and built using local columnar basalt. Within the arch is engraved the iconic statement "For the benefit and enjoyment of the people." The road leading into the park from this entrance leads visitors along the Gardner River and up nearly 1,000 feet (305 m) to Fort Yellowstone and Mammoth Hot Springs.

Kids & Youth

What fascinates you about Yellowstone? Personalize your online adventure of the world's first national park. |

Last updated: April 17, 2025