Kerry A. Gunther, Katharine R. Wilmot, Steven L. Cain, Travis Wyman, Eric G. Reinertson, & Amanda M. Bramblett From Yellowstone Science 23(2): 2015, pages 33-39. Bears, especially grizzly bears, have ferocious reputations that inspire fear and awe in many people.Grizzly bears' long claws and large canines–combined with their size, strength, speed, agility, and predatory nature–contribute to this reputation.Grizzly bears sometimes attack people during surprise encounters, and on rare occasions even prey on and consume humans (Herrero 1985). Therefore, some people believe grizzly bears are not suited for human-dominated landscapes.The iconic status of grizzly bears as symbols of remote wilderness lends further credence to their presumed incompatibility with humans.It is certainly true that grizzly bears survive best, and need the least amount of management attention, in large, remote wilderness areas.However, once the indiscriminate poisoning, trapping, and shooting of grizzly bears ceased during the early 1970s and modern predator management practices were implemented, grizzly bears have shown remarkable resilience and tolerance in the face of ever-increasing human presence.

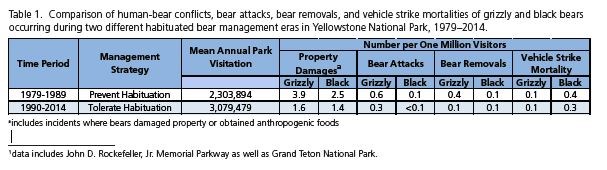

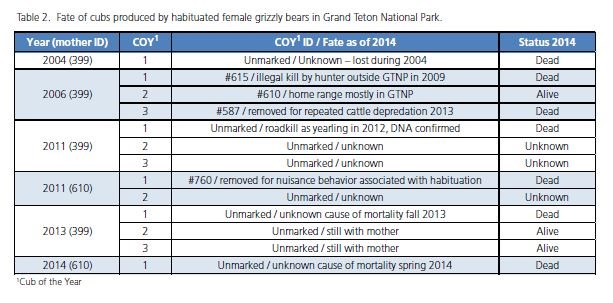

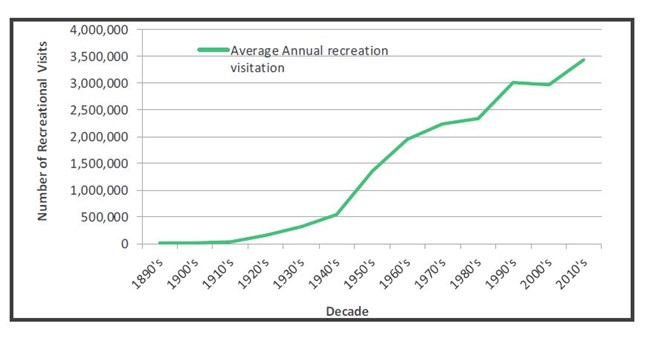

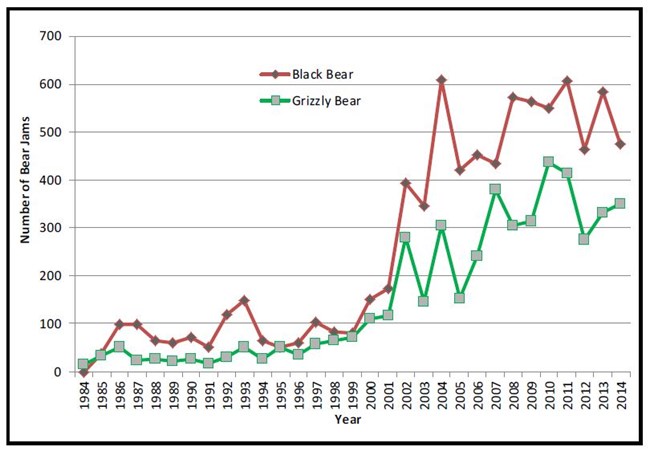

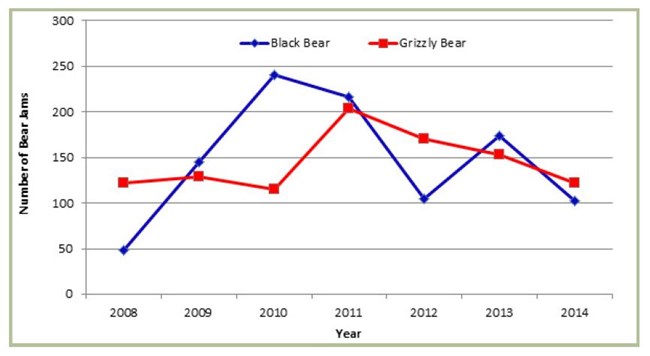

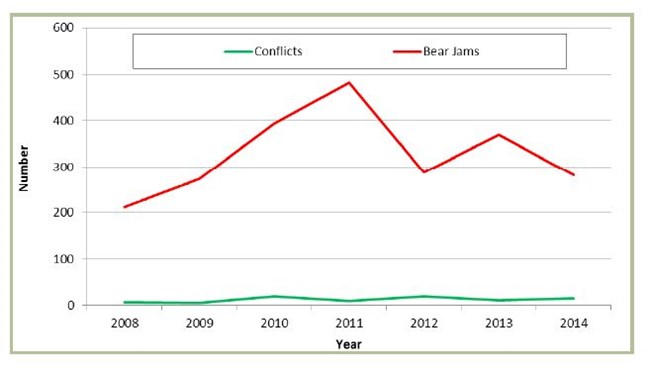

In large national parks where development is minimized, food storage regulations are strongly enforced, and hunting is prohibited, grizzly bears flourish even among high human densities.This is especially apparent with the grizzly bear populations in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks (including John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway) where millions of tourists visit each year and new record highs for visitation are set almost every decade.So how have grizzly bears managed to survive in national parks visited by millions of people each summer? The ability of grizzly and black bears to survive in habitats with relatively high human densities can be attributed to their intelligence, behavioral plasticity, and opportunistic lifestyle, all of which contribute to remarkable adaptability.Habituation to human presence is the behavioral expression of that adaptability.The response of wildlife to humans is shaped by the predictability of human activities (Knight and Cole 1995).When animals experience a non-threatening human activity frequently enough that it becomes expected, they show little overt response (Knight and Cole 1995).Therefore, habituation is the waning of a bear's flight response to people (McCullough 1982, Jope 1985).Habituation is adaptive and conserves energy by reducing unnecessary behavior (McCullough 1982, Smith et al. 2005), such as fleeing from park visitors that are not a threat.Habituation allows bears to access and use habitat near areas with high levels of human activity, thereby increasing habitat effectiveness (Herrero et al. 2005).It is most commonly observed in national parks where exposure to humans is frequent, benign, predictable, and does not result in negative consequences for bears.In these circumstances, bears readily acclimate to predictable human activities (e.g., road traffic) and developments. Habituation differs markedly from food conditioning, which is an entirely opposite learning process (Hopkins et al. 2010).Food-conditioned bears learn to seek humans and their developments for rewards (e.g., human, pet, and livestock foods;garbage), whereas habituated bears learn to ignore people after repeated, non-consequential encounters (Herrero et al. 2005).Human food conditioning invariably gets bears into trouble and ultimately reduces their survival (Gunther et al. 2004).National parks have been successful in decreasing the presence of food-conditioned bears because of strict food storage regulations, relatively high compliance with these regulations, and consistent regulation enforcement and education in developed areas.In contrast to the negative aspects associated with human food conditioning, under certain circumstances habituation can actually improve the fitness of bears by reducing energy expended in response to stimuli that have no consequences, and by giving bears access to additional natural food resources that are avoided by other human-wary bears (Herrero et al. 2005).Evidence suggests habituation is site specific. For example, a bear that displays highly habituated behavior along park roads may be more wary or intolerant of people in backcountry areas where it does not expect to encounter them. Yellowstone (YNP) and Grand Teton (GTNP) national parks have populations of grizzly and black bears, and both parks have experienced significant visitation increases in recent years.Annual visitation to YNP and GTNP currently averages approximately 4 million and 2.7 million visits per year, respectively.Concurrently, both parks have experienced increasing levels of bear habituation in roadside habitats.This, in turn, has led to a growing number of "bear jams," a term used to describe the traffic congestion caused by visitors stopping to view and photograph habituated bears close to roads (Haroldson and Gunther 2013). Yellowstone National Park The year 1970 is considered the beginning of modern-day bear management in YNP.Prior to 1970, due to prevalent hand feeding by park visitors, most bears that frequented roadside habitats were food conditioned.In 1970, YNP implemented a new bear management plan, the foundation of which was to prevent bears from obtaining human foods, garbage, or other anthropogenic attractants (Meagher and Phillips 1983).Under this plan, bears that persisted in trying to obtain human foods and garbage were captured and removed (i.e., euthanized or sent to zoos). By 1979, most bears conditioned to human foods had been removed from the park.However, in the early 1980s a new bear management challenge emerged (Gunther and Wyman 2008).As park visitation and the grizzly and black bear populations increased, bears foraging for native foods that were habituated to people but not conditioned to human foods began to appear in roadside meadows (Haroldson and Gunther 2013).Initially, these roadside bears were not tolerated and were hazed, relocated, or removed by park officials out of concern they would eventually get fed by visitors, damage property, attack people, or get hit by cars. When these tactics failed to prevent habituation, YNP staff adopted an entirely different management strategy that was considered controversial at the time.Beginning in 1990, management efforts focused on humans instead of bears.Rather than trapping or hazing bears, park staff were routinely dispatched to bear jams to ensure visitors parked their vehicles safely, did not approach or feed bears, and behaved in a predictable manner. This strategy has now been in place for 25 years (1990-2014), providing an opportunity to evaluate its efficacy.During this period, 4,587 grizzly bear and 7,618 black bear roadside-jams were documented.An additional 181 bear jams were recorded that did not identify the species of bear present.In total, 12,386 bear jams have been reported since 1990, with no bear attacks on the visitors that had stopped to view and photograph the habituated bears. The concern that tolerating habituated bears along roadways would lead to increases in bear-caused property damages, bear attacks, management removals of bears, and bear mortality from vehicle strikes was unfounded.In fact, humans and vehicles turned out to be more dangerous than roadside bears.Park staff recorded several minor vehicle accidents, and at least five people have sustained injuries when they were hit by vehicles at bear jams. The number of bear-caused property damages, bear attacks, removals of problem bears, and bears being struck and killed by vehicles in the park have all remained low or even decreased under current management strategies (table 1).Human-bear conflicts have remained low despite increasing visitation (figure 1) and a growing number of bear jams (figure 2).However, this strategy does present new challenges for park managers because focusing management on people instead of habituated bears is labor intensive and expensive.Approximately 2,500 to 3,000 personnel hours are spent managing bear jams in YNP annually. Nevertheless, YNP has demonstrated that given adequate staff, habituated bears can be managed along roads in a manner that is relatively safe for both park visitors and bears.Under the current management strategy, thousands of visitors are able to view, photograph, and appreciate bears while visiting the park each year.The opportunity to view bears not only provides a positive visitor experience (Taylor et al. 2014), it contributes millions of dollars to the local economies of gateway communities (Richardson et al. 2014).Positive bear viewing experiences also help build an important appreciation and conservation ethic for bears in people that visit national parks (Herrero et al. 2005). Grand Teton National Park GTNP provides habitat for a stable population of black bears and, to date, an increasing number of grizzly bears as the population continues to expand in numbers and range.Prior to the early 2000s, grizzly bears were rarely observed outside the northern canyons of the park.However, as grizzly bears continued to expand their range, GTNP documented a steady increase in grizzly bear observations, beginning in the north and gradually progressing all the way to the south boundary near Jackson, Wyoming.Observations of habituated grizzly bears followed this trend: first in high visitor-use areas such as Jackson Lake Lodge, Oxbow Bend, Colter Bay, and eventually to the Moose developed area and the Moose-Wilson Road corridor. The first documented observation of a habituated grizzly foraging naturally along roadside habitat in GTNP occurred in 2004.Recognizing the success of YNP's bear management program, GTNP adopted a similar strategy of managing humans at bear jams and tolerating habituated, but non-food-conditioned bears near roads.In 2007, as demands for managing bear jams rapidly escalated, GTNP created the Wildlife Brigade as a pilot program to manage visitors at the human-bear interfaces.The Wildlife Brigade was composed of both paid and volunteer staff. Prior to 2007, GTNP regularly managed periodic black bear jams;but the onset of grizzly bear jams required a reevaluation of GTNP's bear management program, out of which the Wildlife Brigade was born.At about the same time, GTNP transferred management of all frontcountry campgrounds to park concessionaires, and the Wildlife Brigade was designed to also provide food storage patrol and public education in the campgrounds. Since 2008, the first year for which reliable bear jam statistics are available, GTNP has managed at least 1,032 black bear jams, 1,015 grizzly bear jams (figure 3), and 253 bear jams where the species of bear was not recorded.To date, habituated grizzly bear jams in GTNP have been dominated by family groups and sub-adults, the two classes of bears generally considered to be lowest in the bear hierarchy, lending to speculation these bears are using the roadside habitat in an effort to avoid more dominant adult males, which sometimes kill other bears.GTNP saw an almost 100% increase in grizzly bear jam activity from 2010 to 2011, which was attributed to the presence of two related adult females with cubs-of-the-year that foraged naturally along roadside habitats.Presently, it appears annual grizzly bear jam numbers in GTNP fluctuate based on the reproductive cycle and success of a small number of resident females.Not surprisingly, bear jam numbers for both species also seem to reflect the condition of natural foods in the park that occur near roads.The years when GTNP documented high numbers of black bear jams corresponded with years of excellent huckleberry, black hawthorn, or chokecherry crops along the Signal Mountain Summit and Moose-Wilson roads. Although GTNP's experience with habituated bear management is still relatively limited, human-bear conflicts have remained very low (figure 4). There have been no bear-inflicted human injuries associated with bear jams, and no increase in vehicle-strike mortalities of habituated bears has been observed.However, at least 3 of 13 known cubs produced by habituated female grizzly bears have died as a result of circumstances possibly exacerbated by being habituated (table 2).Grizzly bear #615 was illegally killed when she was 3 years old by a hunter at close range on U.S. Forest Service lands just outside GTNP.Her comfort with close human proximity is thought to have contributed to her death.One of two grizzly bears weaned by female grizzly bear #399 as a yearling in 2012 was killed by a vehicle strike later that year.Grizzly bear #760, a habituated, non-food-conditioned male offspring of habituated female grizzly bear #610, was removed after a history of frequenting human developments outside the park.Grizzly bear #587, an offspring of #399 was removed as a 7-year-old for repeated cattle depredation, but as an adult he did not exhibit habituated behavior.In contrast to YNP, which is roughly seven times larger than GTNP and positioned in the center of the grizzly bear recovery area, GTNP's habituated bears may be more likely to leave the protected confines of the park and be susceptible to human-caused mortality associated with inadequate bear-attractant storage or attempts to use habitats in close proximity to people where bears are socially unacceptable. Providing bear viewing opportunities to visitors in GTNP has proven to be very popular for both locals and visitors.Some GTNP bears have become so popular they even have their own Facebook pages.A program large enough to adequately manage the human-bear interface in GTNP using paid employees is cost prohibitive, so the Wildlife Brigade from its inception has been supported largely by volunteers.The 2014 Wildlife Brigade consisted of three paid seasonal park rangers, fifteen volunteers, and one intern which provided human-bear interface coverage seven days a week for over seven months of the year.While the Wildlife Brigade Program has been considered a success, maintaining this level of commitment now and into the future requires substantial financial support. Future Considerations Visitation in Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks is expected to increase into the future.In national parks, habituation of bears to people is inevitable and may be necessary if bears are to survive in park units increasingly dominated by humans.Park managers should take this into consideration when planning future strategies for managing habituated bears.The safety of park visitors that view habituated bears along roadways and the safety of those bears is a legitimate concern for park managers (Herrero et al. 2005).However, to be successful, strategies need to consider not only human and bear safety, but also the energetic needs and nutritional state of habituated bears (Robbins et al. 2004, Haroldson and Gunther 2013), their contribution to bear population viability (Gunther et al. 2004), the aesthetic value of public bear viewing and the conservation awareness this brings (Herrero et al 2005), and the economic value of bear viewing to gateway communities (Richardson et al. 2014). Although the ability of grizzly bears to adapt to increasing visitation undoubtedly has some limits, their behavioral flexibility allows them to exist in a broad continuum of human presence.As a general rule, when human activities in bear habitat increase, staff time and budgets dedicated toward human-bear management require a commensurate increase. Key components of a successful habituated bear management program include preventing bears from becoming conditioned to human foods and garbage, making human activities as predictable as possible, and setting certain boundaries for both bears and people.Appropriate boundaries for habituated bears include teaching them not to enter park developments and campsites or to approach people too closely.Appropriate boundaries for people include teaching them to store anthropogenic attractants in a bear-resistant manner, not to feed bears, and to maintain a minimum distance of at least 100 yards when viewing bears.Although signs, printed material, and website posts are the least expensive media for teaching bear safety and bear viewing etiquette to park visitors, retention of safety messages is highest when presented using face-to-face interactions with uniformed park staff (Taylor et al. 2014).The most formidable challenge for managing habituated bears in national parks is not managing the bears, but in sustaining and expanding the people management programs that have made habituated bear management a success in the parks to date.Habituation is a relatively new challenge faced by bear managers throughout the world, and many of these managers are viewing the Yellowstone and Grand Teton national parks models of habituated bear management with great interest while formulating their own strategies. Literature Cited Gunther, K.A., K. Tonnessen, P. Dratch, and C. Servheen. 2004. Management of habituated grizzly bears in North America: report from a workshop. Transactions of the 69th North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. Washington, D.C., USA. Gunther, K.A., and T. Wyman. 2008. Human habituated bears: the next challenge in bear management in Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone Science 16:35-41. Haroldson, M.A., and K.A. Gunther. 2013. Roadside bear viewing opportunities in Yellowstone National Park: characteristics, trends, and influence of whitebark pine.Ursus 24:27-41. Herrero, S. 1985. Bear attacks: their causes and avoidance. Winchester Press, Piscataway,New Jersey, USA. Herrero, S., T. Smith, T.D. DeBruyn, K.A. Gunther, and C.A. Matt. 2005. Brown bear habituation to people: safety risks and benefits.Wildlife Society Bulletin 33:362–373. Hopkins, J.B., S. Herrero, R.T. Shideler, K.A. Gunther, C.C. Schwartz, and S.T. Kalinowski.2010. A proposed lexicon of terms and concepts for human-bear management in North America. Ursus 21:154-168. Jope, K.L. 1985. Implications of grizzly bear habituation to hikers. Wildlife Society Bulletin 13:32–37. Knight, R.L., and D.N. Cole. 1995. Factors that influence wildlife responses to recreationists.Pages 71-79 in R.L. Knight and K.J. Gutzwiller, editors. Wildlife and recreationists, coexistence through management and research. Island Press, Covelo, California, USA. McCullough, D.R. 1982. Behavior, bears, and humans. Wildlife Society Bulletin 10:27-33. Meagher, M.M. and J.R. Phillips. Restoration of natural populations of grizzly and black bears in Yellowstone National Park. International Conference on Bear Research and Management 5:152-158. Richardson, L., T. Rosen, K.A. Gunther, and C.C. Schwartz. 2014. The economics of roadside bear viewing. Journal of Environmental Management 140:102-110. Robbins, C.T., C.C. Schwartz, and L.A. Felicetti. 2004. Nutritional ecology of ursids: a review of newer methods and management implications. Ursus 15:161–171. Smith, T.S., S. Herrero, and T.D. DeBruyn. 2005. Alaskan brown bears, humans, and habituation. Ursus 16:1–10. Taylor, P.A., K.A. Gunther, and B.D. Grandjean. 2014. Viewing an iconic animal in an iconic national park: bears and people in Yellowstone. The George Wright Forum 31:300-310.

|

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.