A Mule and a Barrel of Whiskey The Wintu and their indigenous ancestors inhabited the area now known as Whiskeytown National Recreation Area for centuries and probably knew about gold deposits, but in the late 1840s and early 1850s, a gold rush comprised mostly of white miners, primarily from the eastern U.S. and Europe, ensued. Thousands upon thousands of newcomers were enticed to California where they mined and settled in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains as well as the Klamath Mountains of northwestern California. Cities such as Shasta, Weaverville, and French Gulch were established to serve miners, and within the present-day boundaries of the national recreation area, a community of Whiskey Town, or Whiskeytown, was formalized about 1852. How did this name come about? Local folklore tells of a miner by the name of Billie Peterson who had a mishap in the early 1850s. While hauling supplies back to his mine, the pack on his mule’s back broke loose and a whiskey barrel tumbled down the hillside, breaking on rocks below and spilling its contents into a creek. From this christening came the name Whiskey Creek, and the small settlement next to the creek became known as Whiskeytown. (In the photo at the top of this page, at President Kennedy’s dedication of Whiskeytown Dam in 1963, Paul McDermott, a colorful and longtime local resident, attempted to recreate this "christening of Whiskeytown" scene). However the Whiskeytown name came about, miners were often known to be good drinkers, and whiskey was in fact a common alcoholic beverage of the era. Whiskeytown’s early businesses attest to this, as by the mid-1850s the community of about 1,000 people included several saloons. There was also a general store that sold several different types of whiskey. Just imagine this whiskey-drinking scene: mostly white, mostly male miners working hard trying to dig, pick, pan, and blast a living out of the earth by day, but in the evenings, during bad weather, or on Sundays, what were these single men to do? They washed clothes, washed themselves, and bought supplies, but certainly many of them drank to relax and unwind and not think about all their problems – pretty much the same reasons many people drink today!

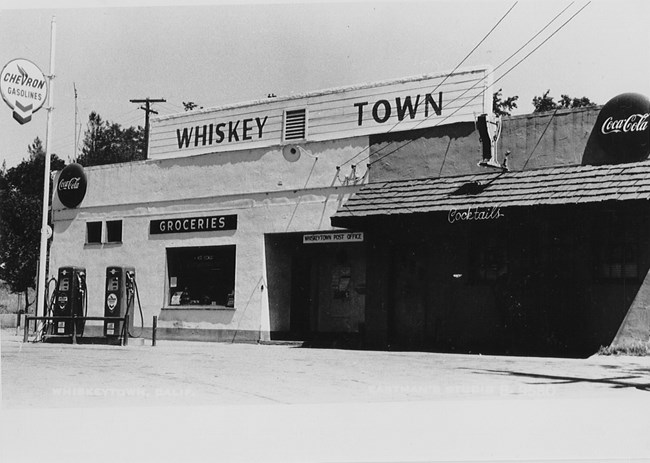

While Whiskeytown was never as large as the towns of Shasta or Weaverville, it did become a small hub and a comfortable stopover for travelers. Located along a main travel route, pack trains and stagecoaches carried supplies and people to and through town on the way to other mining communities. In addition to the several saloons, by 1855 Whiskeytown boasted a hotel, school, stable, and post office. At its peak, the community included about 1,000 residents. By the 1870s, the vast majority of gold deposits in the area had been extracted. But although Whiskeytown substantially reduced in size, it did not fully succumb to ghost town status. Some mining for gold and other minerals continued off and on for decades in and around Whiskeytown, and others ranched, farmed, or served the few travelers passing through. During the Great Depression of the 1930s, with millions unemployed and standing in bread lines across the country, some individuals left their homes to try a new beginning. Back-to-the-land and subsistence farming movements gained momentum, and one of the families that came to the Whiskeytown area to do just this was Paul McDermott and his brother, sister, father, and mother. Aside from some new families moving into the area, the Whiskeytown School received a facelift during this time courtesy of federal government funding by way of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. While most residents and maps continued to refer to the small community as Whiskeytown, for several decades, the U.S. Postal Service refused to acknowledge the name because they apparently felt it was unwholesome. As a result, the town and specifically the post office was formally noted by many other names including Stella, Blair, Whiskey Creek, and Schilling. This all changed in 1952 when the Women’s Improvement League of Whiskeytown, a group of community-active ladies, successfully campaigned to have the Whiskeytown name officially adopted by the Post Office. Throughout this whole time, the town remained inhabited but relatively quiet and with some derelict buildings.

As years grew to decades, the concept of claiming the waters of northern California for Central Valley agriculture became popular. After the construction of Shasta Lake and Dam in the 1940s, plans to bring Trinity River water over the mountains to the Sacramento River grew strong. Whiskeytown Lake and Dam became part of this major reclamation initiative. Before flooding the valley in the early 1960s, almost all property was purchased from Whiskeytown residents. A few homes and businesses were moved down the highway to the town of Shasta. Among the few structures saved were the post office and general store building as well as the cemetery. The general store in particular moved to a site near the present day Whiskey Creek Day Use Area on Whiskey Creek Road, above the full pool level of the lake. The historic Whiskeytown Cemetery was moved to its current location below the dam in the early 1960s; bodies were exhumed and then reinterred. Though the cemetery was partially destroyed during the Carr Fire, burials continue periodically to this day. The Whiskeytown Cemetery is overseen by the Shasta County Sheriff's Office and is known today for being both historic and whimsical. In the summer of 1963 dammed waters filled the valley where once stood the small community of Whiskeytown. When U.S. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy dedicated Whiskeytown Dam in September, some people speculate that the reason he decided to come to Whiskeytown was because of its bizarre name! In the president's opening remarks at the dam dedication ceremony, he said:

‘I have fallen in love with American names, The sharp names that never get fat, The snakeskin titles of mining claims, The plumed war bonnet of Medicine Hat, Tucson and Deadwood and Lost Mule Flat.’ “Then he goes on to talk about some famous American names, not Whiskeytown, but I think he could add it to the roster, because the name of this community tells a good deal about the early beginnings of this state and country.” Two years after JFK's dedication of Whiskeytown Dam, Congress passed and U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson signed into law legislation creating what is officially known as Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area. Located just above lake level, the Whiskeytown General Store continued to operate as a private business surrounded by the park for decades, its doors finally closing in the late 1990s. The store remnants as well as a couple of park residences situated nearby burned to the ground during the 2018 Carr Fire. Ironically, to this day, a green highway sign on U.S. 299 points to the town of Whiskeytown – but the town is population zero! Be that as it may, an odd name is preserved via the names Whiskeytown Lake, Whiskeytown Dam (redesignated the Clair A. Hill Whiskeytown Dam in 1989), and Whiskeytown National Recreation Area. If you are inclined to drink responsibly while in the park, perhaps on your next visit to the national recreation area, perhaps on a hot summer day, pop open and respectfully drink a cold one, maybe even take a shot of whiskey. As you do so, you might consider saluting the memory of Whiskeytown. May the name live on. |

Last updated: February 10, 2022