Learn more about these symbols and stories: • The Flag • The National Anthem • The First Lady • Uncle Sam

The FlagThe War of 1812 elevated the American flag to icon status. Before the war, Americans rarely used the flag to express patriotism. But the flag’s appearance over Fort McHenry during the Battle for Baltimore and Francis Scott Key’s poem “The Star-Spangled Banner” inspired the public. After the war, the flag was often displayed as a symbol of national pride and unity. Major George Armistead wanted to show the British that Fort McHenry was ready to fight. “We, sir, are ready at Fort McHenry to defend Baltimore against invading by the enemy,” he said to American General Samuel Smith, who commanded all forces in and around the city. “That is to say, we are ready except that we have no suitable ensign to display over the Star Fort and it is my desire to have a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance.” In the summer of 1813, Armistead commissioned Mary Pickersgill, a second-generation flag maker, to make an “American ensign 30 by 42 feet” of “first quality bunting.” When Fort McHenry held off the British navy during the Battle for Baltimore in September 1814, Pickersgill’s flag was hoisted in a triumph over the fort. After a long journey from family keepsake to national treasure, Fort McHenry’s flag found a home at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. An American flag flies over Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, a reminder of the iconic flag that inspired the words to what became the national anthem of the United States of America. Visitors learn the flag’s story through exhibits and ranger-led programs. The National AnthemThe War of 1812 also produced the national anthem of the United States of America. Francis Scott Key was inspired to write “The Star-Spangled Banner” after watching Fort McHenry survive the British bombardment. Key’s new lyrics to a popular tune of the day gained instant popularity in the days after the Battle for Baltimore, but it didn’t become the official national anthem for more than 100 years. During the Civil War, bands played it regularly. The US Navy made it an official part of its flag ceremonies in 1889, and President Woodrow Wilson ordered it to be played for military ceremonies during World War I. In 1929, the popular newspaper cartoon series “Ripley’s Believe or Not!” noted that the country had no national anthem. Well-known composer John Philip Sousa published his endorsement of Francis Scott Key’s “soul-stirring” lyrics, and a public campaign began to promote “The Star-Spangled Banner.” President Herbert Hoover finally signed a law on March 3, 1931, to make Key’s song the official national anthem.

The First LadyThe role of the first lady gained greater visibility during the War of 1812 era, thanks to the gregarious, charming and fashionable Dolley Madison. Legend has it she was the first to be called “first lady” when President Zachary Taylor delivered her eulogy in 1849. Dolley set a standard to which many future first ladies would aspire.The consummate White House (then known as the “President’s house”) hostess, Dolley brought sophistication to the capital. During her husband’s presidency, Washington was still a small city, and hardly cosmopolitan. In the words of Attorney General Richard Rush, it was “a meager village, a place with a few bad houses and extensive swamps.” President James Madison was an awkward, dour man. His wife, in contrast, was warm and welcoming, and she took the lead hosting political figures and events. Dolley’s fame increased after the burning of Washington. In August 1814, with the British only miles away, she was still at the White House, trying to save as many of the nation’s documents and treasures as she could. When she returned to Washington after the British occupation, Dolley reinstated her Wednesday evening "drawing rooms" (receptions), which were popular with politicians, diplomats, and other Washingtonians. Dolley Madison helped shaped the role of first ladies in public service. She was the first to formally support a public project when she helped found a home for orphaned girls in Washington.

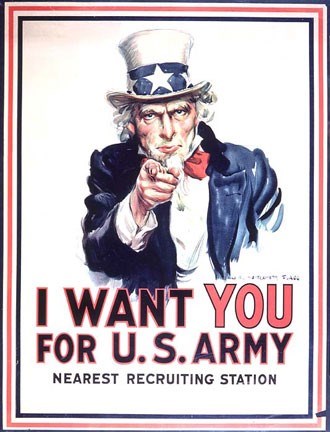

Uncle SamThe figure “Brother Jonathan” personified the United States during the Revolutionary War, but during the War of 1812, his successor—“Uncle Sam”—was invented.The moniker “Uncle Sam” was probably coined in reference to businessman Sam Wilson, who supplied American troops along the Canadian border with barrels of meat stamped with “U.S.” This, of course, stood for “United States,” but soldiers joked that the rations were from “Uncle Sam.” The term became popular in reference to supplies or gifts from the government, but it was just a name. A visual representation of Uncle Sam didn’t appear until 1832. His image evolved over the next 30 years. Uncle Sam and Brother Jonathan were both popular icons through the Civil War, but eventually Uncle Sam incorporated traits from Brother Jonathan—and President Abraham Lincoln—to become the dominant icon. By the late 1850s, Americans knew Uncle Sam as a serious, grandfatherly man with a white beard who dressed in red, white, and blue stripes and a top hat. The best-known portrait of Uncle Sam appeared on World War I military recruitment posters, which featured him pointing his finger directly at young men and saying “I want you.” |

Last updated: April 7, 2020