During the summer of 1814, the British harassed U.S. citizens, raided tidewater towns and farms, largely overwhelmed the militia, and blockaded the U.S. Navy Chesapeake Flotilla—thus keeping it from carrying out its mission to protect American interests. From June through October 1814, the war raged through the Chesapeake Bay region. The Chesapeake Campaign involved two principal military initiatives led by British Rear Admiral Cockburn during the summer of 1814. The first effort was the assault on Washington, DC while employing diversionary feints along the region’s waterways. The second thrust was an attempt to subdue Baltimore. Since most of the regular U.S. Army was fighting on the Canadian border, defense of the Chesapeake Bay and the nation’s capital fell largely to poorly trained and inexperienced militia (citizen soldiers). In June, the British launched their attack. The main British fleet headed north up the Patuxent River to first engage the Chesapeake Flotilla in the Battles of St. Leonards Creek, and then disembark troops to march overland to Washington, DC. A British squadron entered the Potomac River to take Fort Washington and to provide a water retreat route from Washington if needed by the British land forces. A third smaller naval force traveled up the Chesapeake to raid the upper Bay north of Baltimore and to further confuse and divert American forces.

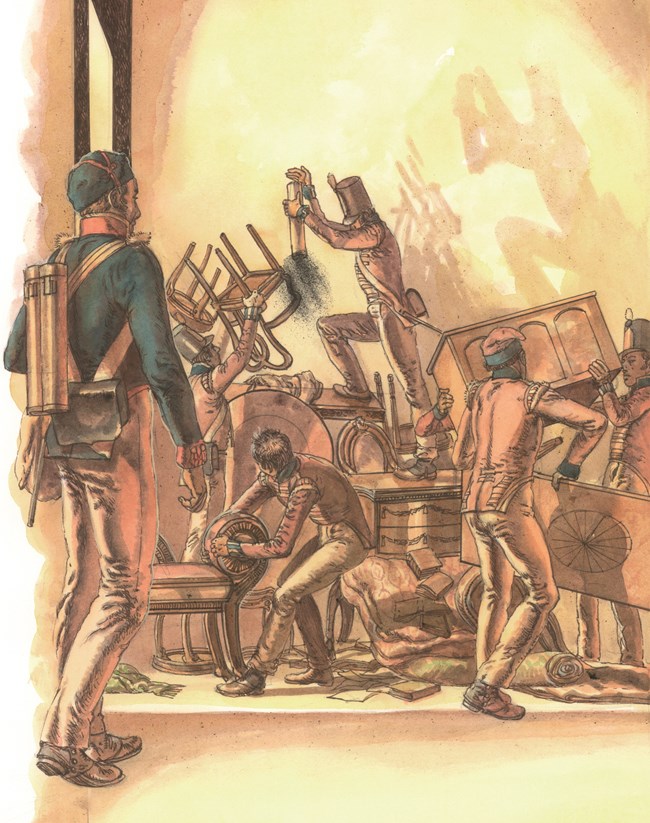

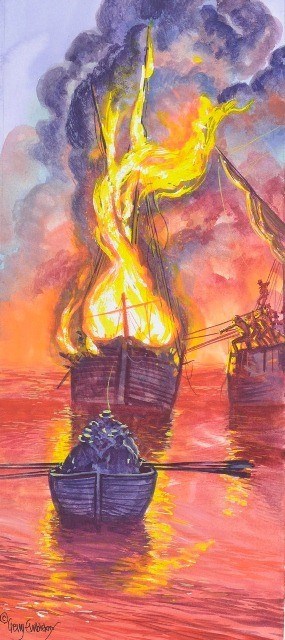

A rocket fired into the heap provided ignition and resulted in a substantial fire. (c) Gerry Embleton President Madison and his cabinet, realizing the danger, fled to safety. At the White House, Dolley Madison quickly arranged to secure and remove what documents and treasures she and her enslaved helpers could, including a Gilbert Stuart portrait of President George Washington. Irreplaceable documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution had been rushed to safety in Virginia the day before. The occupation of Washington lasted only about a day, and the enemy targeted only public buildings, but the Americans were demoralized. On the Potomac, British naval forces had to pass Fort Washington to reach Washington, DC. On August 27, American soldiers destroyed the fort to keep it out of enemy hands, clearing the way for the British to continue up the river, where officials from Alexandria, VA, offered to capitulate in order to spare the town any damage. British troops occupied Alexandria from August 28 to September 3, taking merchant ships and commodities such as flour, tobacco, and cotton.

By mid-September, the fleet had advanced to the Patapsco River where about 4,500 British troops landed at North Point and began an 11-mile march to Baltimore. As the land troops made their way toward the city, British warships moved up the Patapsco River toward Fort McHenry and the other defenses around the entrance to Baltimore Harbor. On land, during a skirmish prior to the Battle of North Point, British Major General Robert Ross was mortally wounded. The British troops nevertheless defeated the Americans at the Battle of North Point and after encamping for the night continued toward the outskirts of Baltimore. There they encountered impressive, over one-mile-long earthworks, manned by an estimated 15,000 Americans, dug in to defend against the British troops’ eastern approach to Baltimore. Humiliated by the defeat two weeks earlier at the Battle of Bladensburg, American militia from many parts of the mid-Atlantic region joined Baltimore residents in preparing for an attack. British ships, anchored off Fort McHenry, began a 25-hour bombardment of the fort on September 13, but failed to force its commander, Major George Armistead, and the other defenders to surrender. As the British fleet withdrew down the Patapsco River, the enormous garrison flag now known as the Star-Spangled Banner was raised over Fort McHenry, replacing the smaller storm flag that flew during most, if not all, of the bombardment. Hearing of the failure of the British fleet to take Fort McHenry, British land forces, now without naval gun support, prudently decided to withdraw as well. The Americans’ successful land and sea defense of Baltimore convinced the British to withdraw most of their troops from the Chesapeake region. A small contingent remained and raids continued into 1815. Just days before the Battle for Baltimore, the British fleet in Lake Champlain on the U.S. and Canadian border, was defeated, ending the British invasion down the Hudson River. These defeats and the high cost of fighting a war on foreign soil led the British to agree to a peace treaty with very few conditions. In January 1815, with neither side aware that the treaty had been signed the previous month (though not yet ratified), the British decisively lost the Battle of New Orleans. It took several weeks for the treaty document to cross the Atlantic under sail and reach Washington. The U.S. Senate unanimously approved the Treaty of Ghent on February 16, 1815; President James Madison signed the treaty the next day. The war was now officially over. |

Last updated: June 4, 2020