Last updated: February 17, 2025

Place

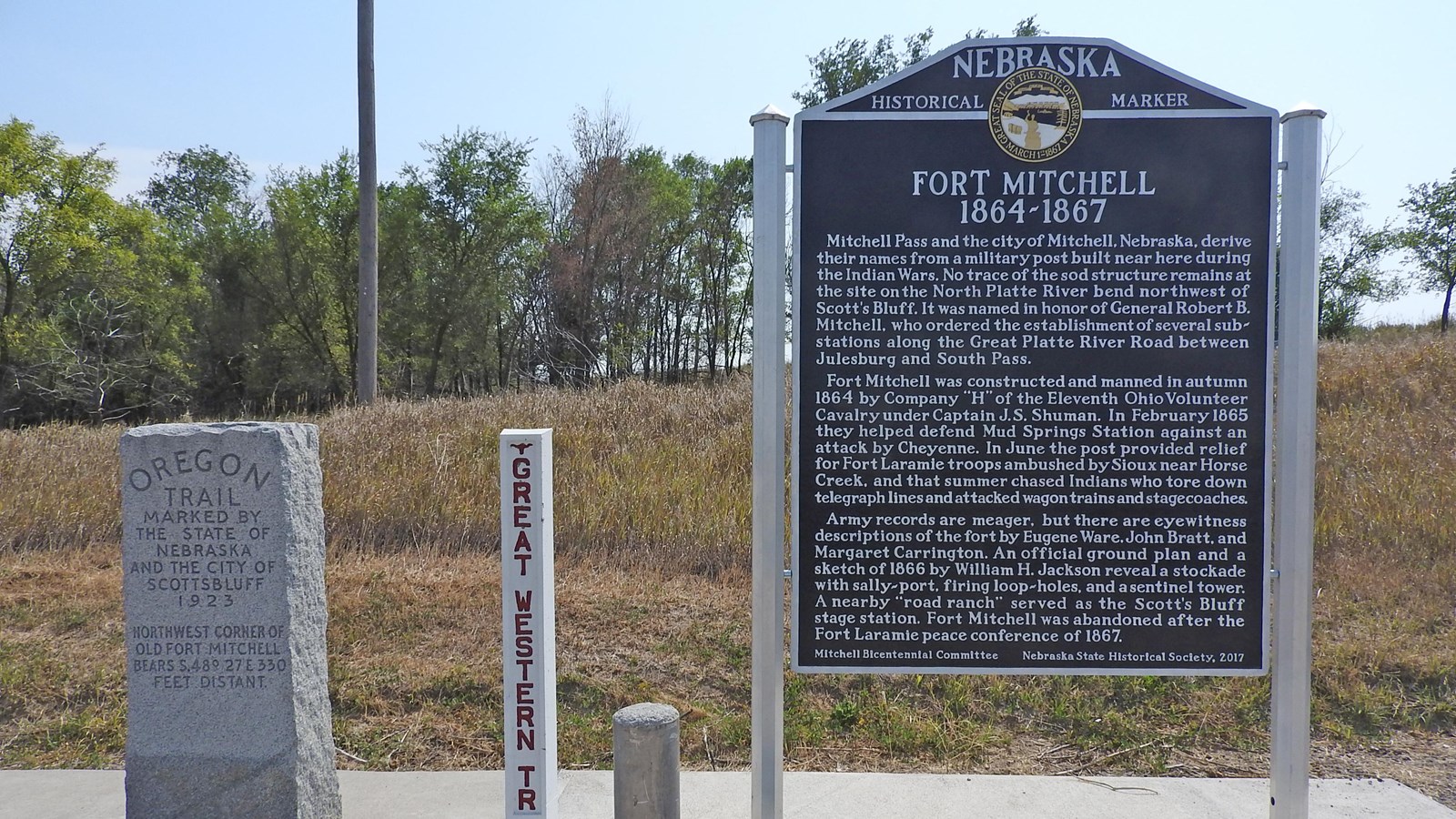

Fort Mitchell Site

NPS/Eric Grunwald

Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Parking - Auto

Forgotten Outpost

During America’s westward expansion, the United States Army established hundreds of small outposts throughout the frontier to protect settlers, maintain communication with the West Coast, and serve as staging areas for military campaigns. Some of these posts have become an integral part of American history, such as Fort Leavenworth and Fort Riley in Kansas and Fort Laramie in Wyoming. Most served less conspicuously and then faded into obscurity. One such outpost was Nebraska Territory’s Fort Mitchell.

Protecting the West

The American Civil War brought a new significance to the western territories. The great overland roads such as Santa Fe, Oregon and California Trails continued to carry vast numbers of emigrants and tons of freight. Western gold fields were producing ore that helped finance the Federal government’s war effort, and the newly erected transcontinental telegraph lines helped bind westerners to the Union. But eastern battlefields drained regular Army soldiers from the frontier and left vital western territories unprotected.To provide a military presence in the West, the Federal government sent a few state raised volunteer cavalry regiments to garrison forts that had been vacated by the regulars. Among these volunteers were the 11th Ohio Cavalry, under the command of Colonel William O. Collins, who arrived in Nebraska territory in 1862. After marching west to Fort Laramie, they were immediately assigned the task of patrolling, escorting freight wagons and stage coaches, and maintaining the telegraph lines along the Oregon Trail in central Wyoming. Eventually, other units from Iowa, Nebraska and Kansas joined the Ohioans on the frontier.

Fight to Control the Plains

Traffic over the roads continued unabated until early August 1864, when the plains erupted in violence that pitted the volunteer soldiers against Sioux, Arapaho, and Southern Cheyenne warriors. Determined to drive the Americans from their lands, plains warriors swept out of Kansas and attacked homesteaders, stage stations and freight caravans all along the Platte River. For several weeks, all traffic and communications over the Oregon Trail came to a halt. In response to these depredations, several military expeditions sought out the warring tribes, but failed to bring them into battle. This led Brigadier General Robert Mitchell to work to assure that the overland roads would never again be at the mercy of a hostile enemy.

A New Strategy

The general planned to fortify each stage station along the Oregon Trail and detail troops to protect them. He also decided to build two new forts at strategic sites along the Platte River. To help defend the road that branched off the Oregon Trail and followed the South Platte to Denver, the first post was built near Julesburg, Colorado. For the first year of its existence, this post was known as Fort Rankin, and had a garrison of soldiers from the 7th Iowa Cavalry. It proved its value by withstanding two Native American assaults in the early weeks of 1865, and later served to protect workers during the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. The second post was placed along the North Platte River near Scotts Bluff. Official records documenting Fort Mitchell’s history are meager, but construction had begun by September 1, 1864, the date General Mitchell visited the site. The general’s aide-de-camp noted that the men of the 11th Ohio’s Company F were hard at work building the sod structure. Captain Jacob Shuman, the first commander of the as yet unnamed post, gave General Mitchell a tour of the site and described his plans for a sod stockade he hoped to have finished before winter set in. By the end of October, most of the work had been completed and the post was named for the general who had ordered its construction.

Conflict Grows

Hostilities on the plains intensified after November 29, 1864, when Colorado volunteer soldiers killed several hundred Cheyenne and Arapahos at Sand Creek, Colorado. Rather than bringing an end to the conflict, the massacre at Sand Creek resulted in renewed warfare and bloodshed. Convinced that the southern plains were no longer safe, several Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho bands began to move north to spend the winter in the remote Powder River region of Wyoming. However, enroute they encountered military forces stationed along the overland roads. First, they crossed paths with the 7th Iowa Cavalry at Fort Rankin. On February 2, 1865, the Native Americans stripped the post of anything useful. Two days later, they attacked a fortified telegraph station at Mud Springs, Nebraska. The Native Americans failed to cut the telegraph wires, allowing the 11 desperate soldiers at the tiny outpost to signal Fort Laramie for help. The first cavalrymen to respond came from Fort Mitchell. The siege continued until February 5th, when additional support arrived from Fort Laramie. After some additional skirmishing, the Native American bands crossed the frozen North Platte River and continued northwest.

Seeking Peace

The spring of 1865 saw a short-lived attempt at peace on the frontier. Tired of warfare, the Brule Sioux came in to Fort Laramie and asked to be allowed to live in peace near that post. The Army welcomed the gesture, but was unwilling to support the Indians with rations this far west, and decided to move the band to Fort Kearny in central Nebraska. The wary Sioux were allowed to keep their weapons for the journey, while the cavalry escort was not issued ammunition in hopes of avoiding confrontation. Distrust and fear of being moved near their enemies, the Pawnee, led the Brules to flee just three days into the journey. While trying to prompt the Native Americans into striking camp, the commander of the escort was shot. A skirmish ensued, and reinforcements were sent for from Fort Mitchell. Before relief arrived, the Sioux escaped by crossing the North Platte River and the outnumbered soldiers did not pursue.

Life at the Fort

For the next two years, Fort Mitchell continued to serve as a reassuring force to travelers on the Oregon Trail. Hundreds of freight wagons, emigrant trains and stage coaches passed Fort Mitchell. Detachments from the fort safely escorted them all, despite the fact that the post’s garrison never exceeded 100 men. Conditions at Fort Mitchell were crude and demanding. Endless hours of patrol and escort duty were interrupted only by the constant maintenance of the fort’s sod walls and corrals. Poor sanitary conditions and a monotonous diet of hardtack and salt pork added to the soldier’s hardships. Despite the poor living conditions, only one man is known to have died at Fort Mitchell. Following the end of the Civil War, regular army soldiers returned to the West, and one company of the 18th Infantry was stationed at Fort Mitchell. These foot soldiers were helpless against highly mobile Native American warriors, and once suffered the indignity of having 112 mules stolen from a freight train camped within sight of the fort.

Fading into Obscurity

No official record of the post’s abandonment exists, but Margaret Carrington, wife of Col Henry Carrington, made one of the last accounts of Fort Mitchell as an active military post. The Carringtons stopped at the site in June 1866, and described it as follows: “This is a sub-post of Fort Laramie of peculiar style and compactness. The walls of the quarters are also the outlines of the fort itself, and the four sides of the rectangle are respectively the quarters of offices, soldiers, horses and the warehouse of supplies”. Soon after, Fort Mitchell faded into obscurity. The sod walls quickly deteriorated, and wind and rain removed all signs that the post ever existed. Today, plows turn up occasional reminders of Fort Mitchell in the form of rusted metal artifacts. Although no physical indications of the post remain, nearby Mitchell Pass preserves the name and serves as a reminder that for three years, Fort Mitchell stood guard along the Oregon Trail during an important period in American history.