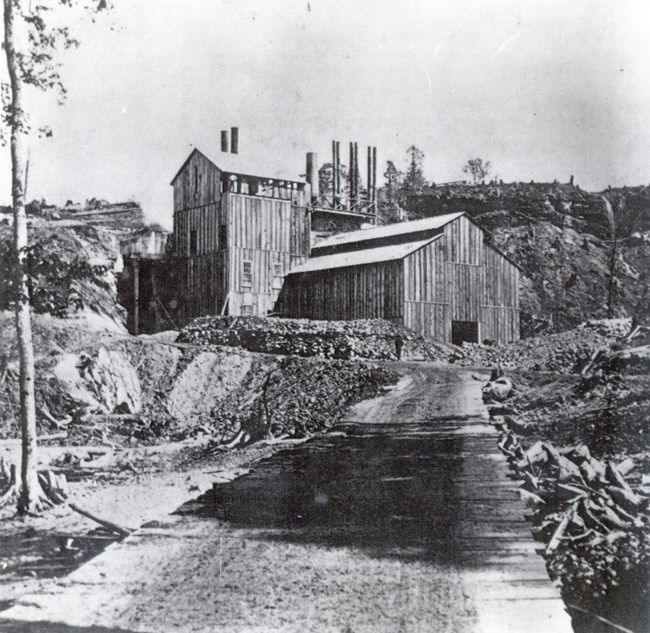

Alger County Historical Society Iron ore was mined in the western Upper Peninsula during this time. Although no ore was mined in the Pictured Rocks area, investors looked to take advantage of the close proximity to the extraction that was occuring in the western half of Upper Peninsula. The Schoolcraft Iron Company was one of the many new ventures in the area, spearheaded by local agents Peter White and Henry Mather and bankrolled by a group of investors in Philadelphia. The Schoolcraft furnace was constructed near Munising Creek using stone quarried on Grand Island, and a “corduroy” log road was built from the furnace to the lakeshore 1,100 feet away. A small community, the first site of the town of Munising, sprang up around the furnace. The furnace first went into blast on June 28, 1867, and within a year was producing up to twenty tons of pig iron each day. The smelting process relied on a variety of resources and transportation networks to produce the finished product. Iron ore was mined in the Marquette area and transported by rail and boat to Munising, while limestone was shipped from the Lake Erie region. Logging crews cut beech and maple trees from the 87,000 acres of company land surrounding the furnace, then placed the cut wood into beehive-shaped kilns to be burned down into charcoal. Over 500 workers were employed to help in this labor, and they and their families made up nearly the entire population of Old Munising.

The furnace experienced turbulent fortunes over its ten years of operation. Shortages of iron or charcoal occasionally caused the furnace to shut down, and poor financial management bankrupted the company in 1870, but the business was reorganized under the direction of Peter White. The furnace was soon running at full production again when the Panic of 1873 and subsequent economic downturn sent the price of iron spiraling. The Panic was blamed largely on over-rapid expansion of railroads into the western US, and new railroad construction virtually stopped as a result. Without its primary buyers, the Schoolcraft furnace never fully recovered. A number of investors attempted to start up the furnace again, but efforts never lasted more than a year. The furnace shut down for the last time in November 1877. The workers in the town of Old Munising were left with few options after the closure, and most residents left the area. The town itself was eventually moved to its current location to be near local logging operations, while the furnace equipment was melted down in 1901 and recast for use in the Keweenaw copper mines.

|

Last updated: January 31, 2022