Last updated: June 30, 2025

Person

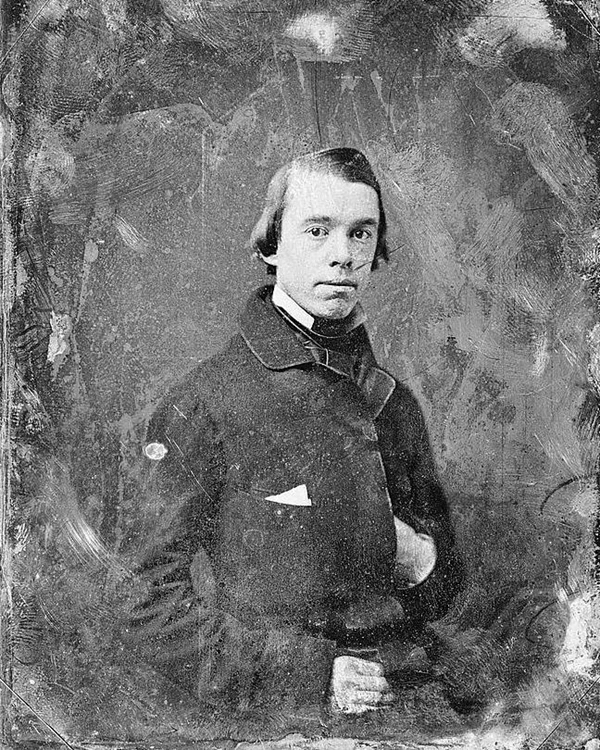

Thomas Starr King

Library of Congress

Boston minister and abolitionist Thomas Starr King served on the 1850 Boston Vigilance Committee.

Born in 1824, Thomas Starr King lived in various places throughout his childhood as his father, an itinerant minister, moved from church to church. The family ultimately settled in Charlestown, Massachusetts. After his father's death, King, at only fifteen years old, had to provide for his mother and siblings.

For a time, he worked as a bookkeeper at the Charlestown Navy Yard, while attending lectures at Harvard and studying independently. Though he never finished school, King followed in his father’s footsteps and became a minister, first at the Charlestown Universalist Church, then at the Hollis Street Church in nearby Boston. He married Julia Wiggin in 1848 and soon began a family with her. To provide for his family, King took to the lecture circuit to augment his salary from the church. He became a prominent and popular orator throughout the region.1

As a minister, King felt compelled to speak out on key social issues including slavery. He wrote, "I would insist as strongly as anyone on the right and duty of ministers to act as reformers, to speak in Anti-Slavery meetings." However, he felt his moderate approach and manner to be more effective than those of the radical abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison.2

Following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, King grew more militant in his tone. From the pulpit, he cast this new law as "a hideous deification of what is base and wrong, and an open defeat in the heart of a Christian people of mercy and Jesus, by injustice and Satan…" He joined the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization that assisted freedom seekers escaping to Boston on the Underground Railroad. Although his name does not appear on the published list of committee members, it is included on Austin Bearse's "Doorman's List." Among other duties, Bearse watched the door at committee meetings and only allowed known members to enter. 3

Following the arrest and rendition of freedom seeker Anthony Burns, King gave a sermon comparing Burns’ ordeal to that of Jesus Christ. He wrote to a friend:

The slave excitement here was intense. I never knew such a stirring up, such inward gnashing of teeth. We were under martial law on Friday, and it turns out illegally so, and if anybody had been shot by the troops, the soldiers would have been liable for murder. The indignation is very deep against the mayor, and that poor Burns, by marching down State Street at noon under military guard, made more Abolitionists than Parker and Phillips have made in a year…I preached on the arrest, trial, and condemnation of Jesus…4

One account stated that although his sermon riled some "ultra-conservatives" of his congregation, "Mr. King has too much strength and moral courage to be deterred from pursuing the path of right and duty by the fear of men."5

In addition to speaking out against slavery, King also called for equal rights for African Americans. In response to the Supreme Court's 1857 Dred Scott decision that declared that African Americans had no rights that white people had to respect, King stated:

We must respect the black man, recognize him as a brother, be ready to help him elevate himself in Northern society, plead against the disabilities that fetter him, [and] pay reverence to him that is due to the victim of arrogant tyranny.6

In another sermon, several year later, he declared, to thunderous applause, "The Almighty has a great mission for this nation. Here the Church is to proclaim the equality of the races."7

In 1860, King and his family moved to California where he helped establish several churches. He also used his leadership and oratory skills to persuade Californians to remain loyal to the United States during the Civil War and to support the efforts of United States Sanitary Commission which aided the war effort.8

Weakened by constant work and travel and battling diphtheria, King died from pneumonia in 1864. Many remembered him as "an able, fearless and uncompromising advocate" in the "cause of human freedom."9

His remains are interred in the First Unitarian Universalist Church Grounds in San Francisco.10

Footnotes:

- Celeste DeRoche and Peter Hughes, "King, Thomas Starr King," The Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, an on-line resource of the Unitarian Universalist Studies Network, King, Thomas Starr - Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Rudolph M. Lapp and Robert J. Chandler, "The Antiracism of Thomas Starr King" Southern California Quarterly, Winter 2000, Vol. 82, No. 4 (Winter 2000), pp. 323-342, 327.

- Quoted in Arliss Ungar, "Homily: Reflections on Thomas Starr King," Homily: Reflections on Thomas Starr King by Arliss Ungar - Starr King School for the Ministry Accessed 6/10/2025; Charles William Wendte, Thomas Starr King, Patriot and Preacher (Boston: Beacon Press, 1921), 19; Austin Bearse, Remininscences of Fugitive Slave Law Days in Boston (Boston: Warren Richardson, 1880), 4; Dean Grodzins, "Constitution or No Constitution, Law or No Law: The Boston Vigilance Committees, 1841-1861," in Matthew Mason, Katheryn P. Viens, and Conrad Edick Wright, eds., Massachusetts and the Civil War: The Commonwealth and National Disunion (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2015), 73, n.57.

- Wendte, 44-45

- "Public Sentiment in Massachusetts," National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 24, 1854, 2.

- Lapp and Chandler, 330.

- Lapp and Chandler, 338.

- DeRiche and Hughes.

- "Death of Rev. T. Starr King," Liberator, April 22, 1864, 2.

- "Thomas Starr King," Find a Grave Memorial.