Last updated: January 12, 2026

Person

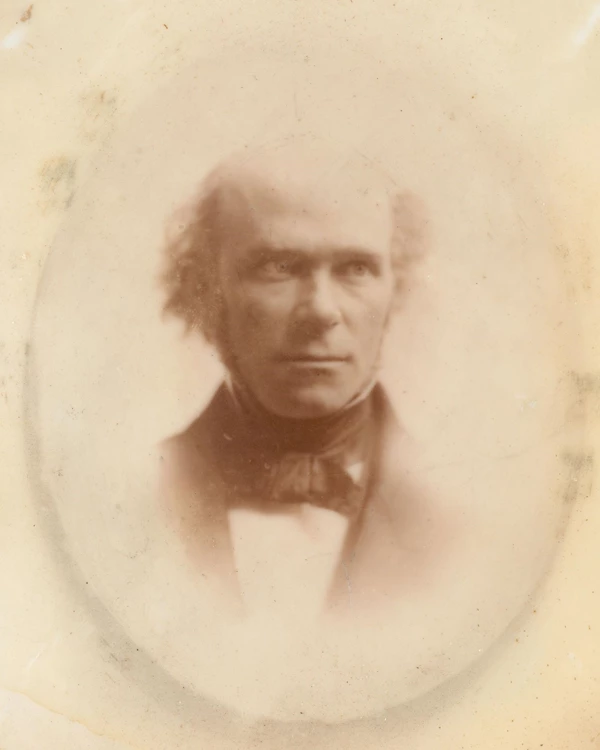

Theodore Parker

Boston Public Library

Theodore Parker rose to fame as a controversial, even heretical, Unitarian minister. Later, his militant opposition to slavery demonstrated that the arc of the moral universe could bend through force of will.

Theodore Parker recognized the legacy and responsibility of the American Revolution from an early age. His grandfather, Captain John Parker, led the Lexington militia on April 19, 1775, the day the Revolutionary War began.1 The youngest of eleven siblings, Parker grew up humbly on a farm in Lexington.2 Incredibly intelligent, he largely educated himself. He could not afford to attend Harvard, so he earned his degree by teaching himself the material and only traveling to campus for exams.3

After saving some money by working as a schoolteacher, Parker continued his studies at Harvard Divinity School. He met Lydia Cabot, a young woman from a wealthy, influential family, during his time as a teacher.4 Their desire to marry led Parker to settle for a pulpit in the Boston suburb of West Roxbury--not his dream position, but one that provided enough financial stability to wed. Their relationship quickly deteriorated, however, as their strong personalities clashed and they discovered they could not conceive children.5

The beginning of Parker's pastoral career coincided with the Transcendentalist controversy of the 1830s, in which Ralph Waldo Emerson and other thinkers explored a nature-based Christianity. Parker took interest as the Transcendentalists cast doubt upon the divinity of Jesus Christ and whether New Testament miracles truly happened.6 He began incorporating Transcendentalist ideas into his sermons, though he tried not to scare away his flock: "I preach abundant heresies," he wrote, "and they all go down—for the listeners do not know how heretical they are."7 In 1841, he brought his beliefs out into the open with a sermon titled, "The Transient and Permanent in Christianity." The sermon represented a complete break with Unitarian orthodoxy and established Parker's reputation as a heretic.8

As Parker's theological infamy grew, so did his interest in social reform causes, such as women's rights, temperance, and the abolition of slavery. In one 1853 sermon, Parker argued that, if humanity followed the laws of nature:

Woman has the same individual right to determine her aim in life, and to follow it; has the same individual rights of body and of spirit,--of mind and conscience, and heart and soul; the same physical rights, the same intellectual, moral, affectional and religious rights, that man has.

He argued that women should be allowed to vote, and to become doctors, lawyers, and ministers.9

Parker wanted to end slavery, though, like many White abolitionists, he maintained White supremacist beliefs and questioned the possibility of racial equality.10 His antislavery work intensified with the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 and the subsequent creation of the third Boston Vigilance Committee.11 Within the organization, Parker served as chairman of the Executive Committee, delivered speeches, and drafted posters.12 He defended William and Ellen Craft from slavecatchers and argued so strongly against the rendition of Anthony Burns that he faced charges of inciting a riot.13

As the debate of slavery intensified through the 1850s, some abolitionists, including Parker, accepted violent tactics and carried weapons.14 John Brown, already famous for killing pro-slavery extremists in the contested Kansas Territory, turned his efforts eastward and planned an uprising in Virginia. Theodore Parker became part of the Secret Six--a group of wealthy benefactors who supplied Brown with money and supplies.15

Parker's health deteriorated as the Secret Six worked to support Brown. He suffered from tuberculosis, the same disease that had caused many premature deaths in his family.16 Following the conventional wisdom of the era, Parker traveled to another climate in the hope of healing his lungs. In the spring of 1859, Parker and his wife ventured first to the Caribbean and then to Europe. He learned of Brown's failed Harpers Ferry raid and impending execution that autumn. Parker wholeheartedly defended Brown's actions in one of his final public statements:

Brown will die, I think, like a martyr, and also like a saint. His noble demeanor, his unflinching bravery, his gentleness, his calm, religious trust in God, and his words of truth and soberness, cannot fail to make a profound impression on the hearts of Northern men; yes, and on Southern men. For 'every human heart is human,' &c. I do not think the money wasted, nor the lives thrown away. Many acorns must be sown to have one come up; even then, the plant grows slow; but it is an Oak at last.17

Theodore Parker died in Florence on May 10, 1860, at just 49 years of age.18

Footnotes

- Paul E. Teed, A Revolutionary Conscience: Theodore Parker and Antebellum America (Lanham: University Press of America, 2012), 1.

- Dean Grodzins, American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2002), 1.

- Grodzins, 22.

- Helen C. Camp, "Theodore Parker," in American Reformers: An H.W. Wilson Biographical Dictionary ed. Alden Whitman (New York: Wilson, 1985), 633.

- Grodzins, 91-102.

- Camp, 633-634.

- Grodzins, 148.

- Henry Mayer, All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery (New York: St. Martin's, 1998), 303-304.

- Theodore Parker, A Sermon on the Public Function of Woman, Preached at the Music Hall, March 27, 1853 (Boston: Robert F. Wallcut, 1853), 12.

William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, ed. Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002), 503-509. - At this time (1850), Parker resided at 1 Exeter Place. Today, this street is likely Avenue de Lafayette in Boston's Downtown Crossing/Chinatown area. As it is unclear which end of the block 1 Exeter Place stood, today's location of his house is either the Ave. de Lafayette Post Office or the Hyatt Regency Boston. National Park Service mapping platforms illustrate the approximate location of the block where Parker resided. George Adams (ed.), The Directory of the City of Boston: Embracing the City Record, a General Directory of the Citizens, and a Special Directory of Trades, Professions, &c. with an Almanac from July 1850, to July 1851 (Boston: Adams, 1850), 257.

- Austin Bearse, Reminiscences of Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston (Boston: Warren Richardson, 1880), 16. Also, Holly Jackson, American Radicals: How Nineteenth-Century Protest Shaped the Nation (New York: Crown, 2019), 185.

- Edward J. Renehan, Jr., The Secret Six: The True Tale of the Men Who Conspired with John Brown (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1997), 50-51. Also, Dean Grodzins, "Slave Law Versus Lynch Law: Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Theodore Parker, and the Fugitive Slave Crisis, 1850-1855," Massachusetts Historical Review 12 (2010): 1-2.

- Renehan, 50; Camp, 635; Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin, 2012), 187.

- Renehan, 145-147.

- Sheila M. Rothman, Living in the Shadow of Death: Tuberculosis and the Social Experience of Illness in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1994), 15.

- Theodore Parker, John Brown's Expedition: A Letter from Theodore Parker, at Rome, to Francis Jackson, Boston (Boston: The Fraternity, 1860), 18.

- Teed, 223-236.