Last updated: September 28, 2020

Person

Jessie Benton Frémont: Anti-Slavery Advocacy at Black Point

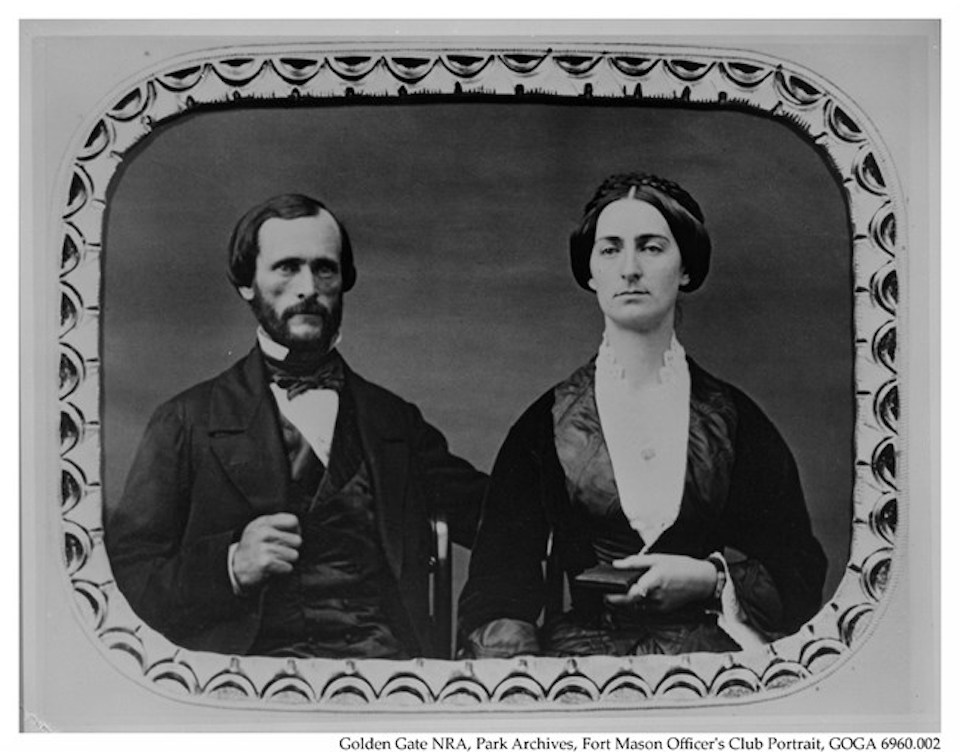

Jessie Benton Frémont. Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Park Archives

When we think of the geographic areas that highlight the Civil War, we generally think of the bloody battlegrounds in the South and Northeast and the routes of the Underground Railroad. California does not ordinarily spring to mind.

Yet right here in Golden Gate National Recreation Area is a site that reveals how California was pivotal in the fight against slavery. That site is Black Point, the farthest bluff of what is now Fort Mason, overlooking Alcatraz and the San Francisco Bay. In 1860 it was the home of Jessie Benton Frémont who hosted an abolitionist salon.

Abolitionist Roots

Jessie Benton Frémont moved to a house on Black Point on the eve of the Civil War. As the daughter of a prominent anti-slavery senator from Missouri, Jessie was raised in the thick of political life in Washington, D.C. Their home was filled with “salons,” lively political discussions, attended by writers, artists, and the leading politicians of the day – including some future presidents. Her husband John C. Frémont, was lauded as the “Pathfinder” for his explorations of the American West. Yet during those expeditions, Frémont was responsible for the brutal killing of native peoples, including the slaughter of perhaps up to 1,000 Wintu in the Sacramento River area in1846.

John Frémont was elected one of the first Senators from the new state of California, and supported numerous bills against the extension of slavery. He also sponsored legislation to confiscate Indian land. In 1856, he was selected (over Abe Lincoln) as the first presidential candidate of the Republican Party and ran on an anti-slavery platform.

When the family relocated to San Francisco from the remote Bear Valley where John ran a prosperous gold mine, Jessie befriended Reverend Thomas Starr King. The Unitarian minister was known for his powerful abolitionist sermons and his advocacy for the rights of free Blacks. She invited King to use a quiet study behind her Black Point home to write his fiery speeches. As the rumblings of war grew louder, the two friends united by a passionate concern about the fate of the Union and the end of slavery, lit upon the idea of hosting a literary and political salon. Writer Bret Harte, whose stories greatly influenced Americans’ thinking about life in the West, and E.D. Baker, a friend of President Abe Lincoln who successfully represented runaway slaves in their bid for freedom, often joined the salons. Even Moby Dick author Herman Melville stopped in.

Division in the State

There was a small but well-organized African American community in San Francisco that published its own newspaper and campaigned for voting rights and anti-discrimination laws. The community was rightfully angered when the state legislature almost passed a Fugitive Slave Law (even though California was a Free State) and about rumors that California might join the Confederacy.

Many California politicians had left the South for the Gold Rush and still supported the Confederacy. While John Frémont had been elected Senator on an anti-slavery platform, the other California Senator, William M. Gwin, was a slaveholder from Tennessee, and was firmly in the proslavery camp. At the outbreak of the war, Gwin returned to the South and became an officer in the Confederate Army.

The Frémonts left Black Point when President Lincoln appointed John to lead the Western Division of the Union Army, based in St. Louis, Missouri. Jessie soon joined him there. Unfortunately their house was razed when Black Point was taken over by the military, and the Frémonts never returned. But in 1860-61 it had served as an important crossroads where influential Californians gathered to share news about the impending war and to pledge their support for the abolition of slavery.