Last updated: September 14, 2017

Person

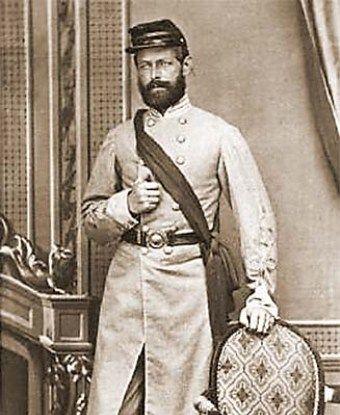

Henry Wirz

National Park Service

"Vat you tink dem Yankees do, if dey get me prisoner, up Nort-eh?... Dey will kill me sure! But I shall take care dey vill no catch me – but if dey do I am certain dey will kill me so quick – so quick, I tell you – dat I shall know nothing about it!" – Sgt. Henry Wirz, Richmond, VA, 1861

Today few Civil War figures are as controversial as Henry Wirz. To some people, he is a martyr or a scapegoat for a failed Confederacy. To others he is the vilest criminal of the war. Few scholars have attempted to tell Wirz's story, leaving it open for supporters and detractors alike to create a mythology to fit their respective agendas. Today, people often approach Wirz with a confirmation bias. They see in his story only that which fits what they already believe. In truth, Wirz was an incredibly complicated figure whose path to Andersonville and the gallows began years before the prison ever opened.

Henry Wirz was born in 1823 in Switzerland. In 1849 he immigrated to the United States and attempted to go into business as a physician in New York City. Failing at this, he moved to Connecticut and then to Northhampton, Massachusetts where he worked as a translator in several small factories. There he took a job working at a water-cure establishment before moving to Kentucky to work as a homeopathic physician. He operated water-cure establishments in Cadiz and Louisville until 1857, when he moved to Louisiana to "take charge of" Cabin Teele, a 2,200 acre plantation owned by Levin R. Marshall. At Cabin Teele, Wirz continued to practice homeopathic medicine while overseeing the hundreds of slaves in bondage there. This was Wirz's first experience with controlling large numbers of people, a skill that would serve him later.

At the outset of the Civil War, Wirz enlisted in the 4th Battalion of Louisiana Infantry, organized in his home of Madison, Louisiana. In the aftermath of Bull Run in July 1861, the unit was sent Richmond, where Wirz was assigned to guard duty at Howard's Factory Prison. He immediately began to organize prisoners, and developed a reputation for efficiency and callousness. He was, as one prisoner wrote in 1862, "the essence of authority at the prison… [he] thought himself omnipresent and omniscient." By the fall of 1861, Wirz attracted the attention of General John Winder, who at that time was in charge of the Richmond prison system. Winder placed Wirz on detached duty as a part of his prison management team. In November 1861 the Richmond newspapers reported that Sergeant Henry Wirz was one of seven men on the city's Prison Board, charged with ensuring the security of all military prisons in Richmond. Serving with Wirz on this board was Captain George C. Gibbs. Three years later the two men worked together at Andersonville, and Gibbs later testified against his colleague.

Wirz's time on the Richmond Prison Board was relatively short-lived. In late November, 1861 he was sent to the prison at Tuscaloosa, Alabama to serve as the assistant to Captain Elias Griswold. At Tuscaloosa, like at most prisons that Wirz worked, prisoners remembered him with mixed feelings. Some recalled that he was instrumental in securing shelter in an unused hotel. At the same time one wrote that, "We have a Sgt Wertz over us as big a tyrant as ever was." Inconsistency proved to be a theme of Wirz's prison management, as one Richmond prisoner described, "He was a good fellow at times, and a very bad one at others. He would show his angular smile of half-stubborn good humor today, and curse us in his fragmentary English tomorrow." Regardless of how prisoners felt about him, the citizens of Tuscaloosa felt Wirz was a competent leader deserving of promotion. When Captain Griswold was transferred, they petitioned General Winder to place Wirz in command of the prison in Tuscaloosa.

In the late spring of 1862, the prisoners from Tuscaloosa were transferred elsewhere for exchange, and Wirz was sent back to Richmond. On June 1, 1862 he was reassigned to serve as the Provost Marshall of Manchester, a community in Richmond that was later consolidated into the city. After only a few days Wirz requested another duty assignment and was placed on General Winder's staff and promoted to Captain, effective June 12, 1862. Within a few months, he was in command of Belle Isle & Libby Prison in Richmond, an assignment which brought him greater responsibilities and a higher profile within the Confederate military prison system. In September he was ordered to go south and document how many prisoners for the purpose of exchange. Reporting directly to Robert Ould, Confederate agent of exchange, Wirz traveled as far as Houston, Texas between September 1862 and the spring of 1863. Upon his return he held a variety of positions, including Chief of Secret Police in Richmond, none of which he liked. He volunteered to deliver recently acquired weapons and ammunition from Charleston to the trans-Mississippi department. In mid-March 1863, Wirz applied for a medical furlough in order to seek treatment for an arm injury that he sustained at some point in the summer or fall of 1862. Wirz claimed that he was injured at the Battle of Seven Pines while serving as an aid to General Joe Johnston. However, his service records are unclear as to the details of this injury, and he was not yet commissioned as an officer when this battle took place. All that is certain is that he sustained a deep tissue injury to his right arm, and that this injury prompted him to request a furlough for medical treatment. What was supposed to have been a four month furlough to Europe for medical care was eventually extended by several months.

By February 1864, Wirz returned and reported to General Winder. Winder, having worked with Wirz before, assigned this experienced officer to the new prison at Camp Sumter Military Prison at Andersonville. Colonel Alexander Persons of the 55th Georgia Infantry commanded the post when Captain Wirz arrived in early March. Wirz bore a letter from General Winder instructing Persons to give command of the prison's interior to Wirz, whom he called "an old prison officer, a very reliable man and capable of governing prisons." Complicating the situation, the Confederate government sent Major Elias Griswold, whom Wirz had worked for in Tuscaloosa, to Andersonville with similar orders to take charge of the stockade around the same time. This mix up was resolved later in the month, and Wirz formally took command of the prison stockade on March 27, 1864.

Wirz immediately began to reorganize the prison to make it more secure and to improve efficiency. He ordered the construction of a deadline to keep prisoners away from the stockade walls. Drawing on his experience documenting prisoners in 1862, he ordered a daily headcount to be taken. Throughout his time at Andersonville he was frustrated by unclear lines of responsibility. He was charged with daily operations inside the prison – this included taking roll, security, and the issuing of rations and supplies. However, a separate officer was in command of the overall Confederate post of Camp Sumter. Each guard regiment had their own command staff of officers that outranked Wirz. The quartermaster's office operated independent of these two commands, as did the hospital. Wirz could request guards or rations, but had no direct authority to acquire these necessities, although he could order them withheld. Wirz's letters to his superiors in Richmond belie his desperation to solve this command debacle. In an effort to alleviate these bureaucratic struggles, General John Winder reported to Andersonville in the summer of 1864. However, he lacked a clear command directive, and the presence of a brigadier general further complicated the chain of command at the prison.

As in Richmond and Tuscaloosa, Wirz displayed inconsistent behavior towards the captives in his care. At times, he proved helpful and sympathetic. On other days he flew into what one prisoner described as a "spasmodic rage." Unable to carry out his orders to maintain the stability and security of the stockade by military means, Wirz used his reputation and behavior to maintain order. Threats were an important tool in his arsenal of control, and he used them liberally. Prisoners who feared him were less likely to challenge the delicate security of the site. He maintained control by employing techniques such as withholding food from individuals and squads. Supplies sent from the north were distributed to guards and a small number of paroled prisoners. Rumors that he murdered prisoners were commonplace. Threats to kill prisoners were even more common; threats that sometimes were fulfilled. In one instance Wirz ordered a guard to shoot a prisoner, which the sentinel did. Wirz later testified that he meant the order as a threat and that he did not think that the guard would actually do it. His experience on a plantation before the war influenced how he punished prisoners – plantation hounds and iron shackles were used to capture and punish escaped prisoners. Verbal threats created an aura of fear. He routinely made statements in front of his staff and prisoners that were intended to cement his tough reputation. For example, one Confederate soldier testified that Wirz ordered a prisoner into the stocks during a rainstorm. The soldier, observing the prisoner was drowning, placed an umbrella over the prisoner and approach Wirz, who replied, "Let the damned Yankee drown." Wirz was unable to control the bureaucracy that plagued the Confederate military prison system, so he controlled the prisoners in the only way he could – through intimidation and punishment.

It was these actions towards the prisoners that ultimately doomed Wirz. As early as 1861, he predicted that he would be hanged for his treatment of prisoners in Richmond, long before he ever imagined the existence of Andersonville. He was arrested at the prison site on May 7, 1865. In a statement to General John Wilson the day of his arrest, Wirz denied responsibility for the atrocity of Andersonville, referring to himself as "…the tool in the hands of [his] superiors."

He was taken to Washington, DC and held in the Old Capitol Prison. He was charged with conspiracy to kill or injure prisoners in violation of the laws of war, which stipulated the prisoners could not be denied access to available food, water, clothing or medical supplies. He was also charged with multiple counts of murder. A few of these murder charges accused Wirz of personally killing prisoners, but most stemmed from orders that he gave to others. His trial received national attention, as the country demanded justice for the deaths of 13,000 American soldiers. Far more soldiers died in captivity at Andersonville than at any battlefield, a fact that was not lost on former prisoners or the northern public. Wirz's attorneys argued that he did all he could, given the difficult circumstances. The shortage of supplies and medical care were well beyond Wirz's authority, and dozens of letters document Wirz's efforts to solve the logistical problems. However, nearly 150 former prisoners, guards, Confederate officials, civilians, and medical staff, testified that Wirz had indeed violated the laws of war by not only withholding available food and supplies, but also by issuing orders that directly resulted in the death of prisoners of war.

One of the great paradoxes of the Wirz Trial is that both prosecution and the defense sought to prove that Wirz was following orders; the prosecutors hoped to convict higher ranking Confederate officials and Wirz hoped to absolve himself by passing responsibility up the chain of command. As in nearly every military tribunal, the "following orders" defense did not work. Wirz could blame the poor logistics and overcrowding on his superiors. But he could not escape his own orders and actions, and was convicted of conspiracy and murder. He was hanged on November 10, 1865 and was eventually buried in the Mount Olivet Cemetery in Washington, DC.

For over one hundred fifty years Henry Wirz has remained a polarizing figure. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson ordered a halt to further military tribunals, saving most of Wirz's named co-conspirators from suffering a similar fate. In the bitter years of Reconstruction, many Southerners turned to Wirz, the most prominent Confederate to be punished for war crimes, as a symbolic martyr of their Lost Cause. Several former Confederates associated with the prison, including Surgeon Randolph Stevenson and Lt. Samuel Davis published books in defense of Wirz. Prisoners continued to publish memoirs vilifying the side of the man that they saw from inside the stockade – a cruel tyrant that threatened them and their comrades. In the heat of these acrimonious debates, conflicting mythologies emerged. Stories were fabricated – stories that Wirz had personally killed hundreds of men, or that the supposed star witness perjured himself, thus proving Wirz's innocence. Every story imaginable to absolve Wirz was concocted – placing blame on Generals Grant or Sherman, or even on the prisoners. A monument was erected in memory of Henry Wirz in the town of Andersonville that further reinforced these increasingly popular notions. In response, prisoners and their descendants further exaggerated the cruelties of Wirz. In the absence of scholarship on the man or the trial, these myths have permeated the popular understanding of Andersonville.

Whether or not Wirz violated the existing laws of war is not subject to debate. The existing legal frameworks of the day stipulated that prisoners must be given access to the same supplies available to the armies in the field. Wirz's own staff members, including his colleague from Richmond who also worked at Andersonville, George Gibbs, testified that Wirz failed to meet that legal obligation. His threats to kill or injure prisoners as a means of control by intimidation backfired on him and reinforced the belief that he was withholding things not to exact a degree of control, but to purposefully torment and kill his captives. The real debates and legacies of Henry Wirz are much bigger than his own actions in the prisons of Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia. Did the difficult circumstances of managing an overcrowded prison in a crumbling Confederacy justify Wirz's decisions and behavior? Should Wirz have been tried by a military tribunal or civil court? Was he legally protected from prosecution? What responsibilities do officers bear for their commands? These are difficult issues that have resurfaced again and again in our history. The legality and process of military justice continue to divide us well into the 21st century.

***A Note on Sources***

Many of the published materials on Henry Wirz were influenced by the political agenda of their authors, and these books and articles frequently perpetuate inaccurate myths of Andersonville and Henry Wirz. Therefore, this article was based on primary source materials from 1861-1865 including:

-Henry Wirz's service records

-The records of the Wirz Trial

- Newspaper records from Richmond, Tuscaloosa and Georgia from during the Civil War

- A biographical interview Henry Wirz gave to a newspaper after his trial

- Prisoner Memoirs from Richmond and Tuscaloosa published before 1864

Written by Chris Barr, 2014