Last updated: September 11, 2025

Person

Gabriel Turner

National Archives/Ancestry

A moment of freedom becomes a lifetime of service – and a mystery

In 1862, Gabriel Turner was a 19-year-old young man, enslaved in Charleston, South Carolina and working on the city’s docks and ships. As fate would have it, he was a regular crew member on board a privately owned steamer called the Planter that the Confederate government contracted to move supplies around Charleston Harbor. In the Spring of 1862, Turner and the other crew members – most notably Robert Smalls – hatched a plan to liberate themselves by sailing the Planter out to the US Naval ships blockading Charleston Harbor. Their plan was successful and by May 14, 1862, Gabriel Turner was a free man. His share of the prize for capturing the Planter came to $400.

In the summer and fall of 1862, the U.S. Navy used the Planter in operations against the Confederates along the coast of South Carolina and Georgia, and it is likely that Turner stayed on, serving as a hired civilian on board the vessel. But he didn’t stay there long. Abraham Allston, the pilot of the Planter testified that he dropped off Gabriel Turner, William Morrison, and another man off at Camp Saxton in 1863. By March of 1863 Turner had officially enlisted as a United States soldier in the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers (later redesignated the 34th United States Colored Troops).

The Planter was not the last time that Turner participated in an act of liberation. In June of 1863, Turner’s company was one of those that participated alongside Harriet Tubman in a raid on the Combahee River that resulted in the liberation of more than 700 people from the rice plantations.

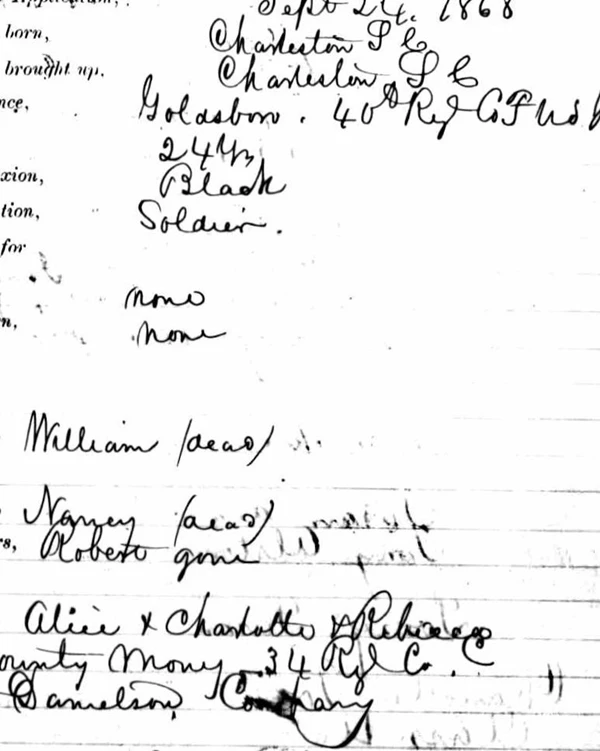

Turner served in the 2nd South Carolina/34th USCT until the end of the Civil War. But it appears that army life suited him. Shortly after his discharge, he joined the 40th United States Infantry, one of the original Buffalo Soldier regiments. During the early years of postwar Reconstruction, the 40th Infantry was stationed at Goldsboro, North Carolina as part of the military occupation of the former Confederacy. After liberating himself, and then liberating others, Turner’s work now meant protecting the rights of his fellow citizens. At some point, Turner received some education, as he signed his own name on both an 1866 Army record and his 1868 Freedman’s Bank deposit record.

The next year, Turner and his comrades in the 40th Infantry were sent to the area around New Orleans, Louisiana. Around this time, the army re-organized, and Turner was discharged from the 40th Infantry in October 1869. Just a few days later, he re-joined the Army in the newly formed 25th Infantry. By 1870, Gabriel Turner, one of the heroes of the Planter, was on the plains of West Texas. He appears in an 1870 Census record as part of the garrison of Fort Stockton, Texas. He spent the next few years engaged in military operations against Native American communities of the southwest. He discharged and re-enlisted at Fort Concho, around 200 miles northwest of San Antonio in October 1874. A year later he was at Fort Davis, where he transferred from Company K to Company B of the 25th Infantry. By the following spring he appears on an army record as a guard at Eagle Springs, Texas. Given his movements, it is likely he was part of military operations to escort and guard the mail service across West Texas. It’s possible he may have even passed through Pine Springs in the Guadalupe Mountains. Gabriel Turner appears to have left the U.S. Army for the last time in October 1879, discharged at Fort Stockton – 17 years and 1,600 miles from where he first tasted freedom aboard the Planter in Charleston, SC

We don’t know what happened to Gabriel Turner after that. Did he remain in West Texas and live out his days in the Black community of West Texas? Perhaps he crossed the border into Mexico, or maybe moved back east. Thus far, his post-military career remains something of mystery. In the late 1800s, even Robert Smalls tried to track down Turner’s whereabouts – but couldn’t find any record of him after his discharge. So far, he has simply vanished. But before he left the army, did he share his past with his fellow soldiers? It’s not hard to imagine him sitting around a campfire somewhere deep in the heart of Texas, and telling stories of the time he ran a steamer past Fort Sumter with Robert Smalls, or when he liberated 756 people alongside the great Harriet Tubman. Would any of his comrades have believed him? Turner’s story is a reminder that the most remarkable of people can turn up in the most unlikely of places.