.gif)

MENU

Chapter 1

Introduction

Chapter 2

Urban Development

Chapter 3

Maritime Activity

Chapter 4

Agriculture

Chapter 5

Industry

Chapter 6

Transportation

Chapter 7

Education

Chapter 8

Religion

Chapter 9

Social/Cultural

Chapter 10

Recommendations

Appendix 1

Patterned Brick Houses

Appendix 2

Stack Houses

Appendix 3

Existing Documentation

|

SOUTHERN NEW JERSEY and the DELAWARE BAY

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route |

|

CHAPTER 6:

TRANSPORTATION (continued)

Modern Highways

Despite the accessibility of trolley and rail transportation, roads were increasingly utilized by travelers, farmers, and laborers. In the late 1870s, the New Jersey Board of Agriculture was prompted to complain about the road systems, whose overseers inadequately maintained them; its constituency, the farmers, were most annoyed as it was their tax dollars intended for the upkeep. In 1891 the Legislature abolished the use of overseers, and road maintenance hence became the responsibility of a township committee that issued bonds to finance road construction. [43] The same year, another law passed providing state aid for the construction of permanent, improved roads, and by 1894, fifty miles of stone roads had already been laid in New Jersey and the first Department of Public Roads was established; six years later, the position of State Supervisor of Roads was created. [44] Furthermore, with the establishment of a prison in Leesburg in 1913, and one existing in Trenton since the nineteenth century, the state easily employed convicts to maintain the roads, as well as quarry materials for building purposes (Fig. 93). [45]

|

| Figure 93. Working on the roadbed in Millville, Main Street/Route 49 at Fifth Street. Wettstein, 1915. |

Today, four state highways make traveling through South Jersey a simpler task. These include Route 49, which runs east/west, and Routes 47, 9, and the Garden State Parkway, which all run north/south. With the exception of the Garden State Parkway, which was constructed in 1953, the other highways follow very close to the original roads cut through South Jersey. Route 9 is considered the oldest road to parallel the Atlantic Coast from Cape May to New York, while Route 47 was one of the first roads that led from Camden to Cape May. The Route 49 corridor from Salem to Jericho appears to have been part of the original King's Highway that was set up in the eighteenth century. Moreover, the portion of this highway that leads from Bridgeton to Millville is part of the original road laid out in the 1800s.

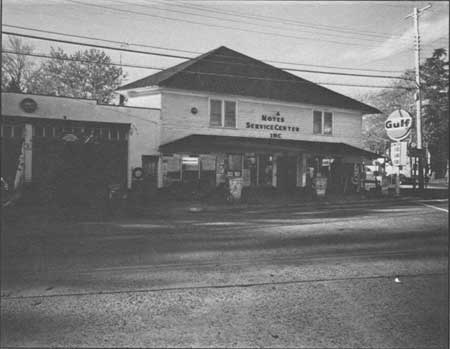

In the early twentieth century, roadside architecture diversified to include a range of automobile-related services: tourist cabins, diners, roadside fruit/vegetable stands, and most important, filling stations. The stations in South Jersey are found mostly along major thoroughfares such as Routes 47 and 49. One of the earliest types is the curbside filling station of the 1920s, where pumps were located "along streets in front of grocery, hardware and other stores which, carrying household petroleum products, had expanded into gasoline sales." [46] Along Route 49 in Shiloh two such filling stations are extant. One is Richardson's General Store, at the intersection of East Avenue; the second is Noyes Service Center at the corner of Route 696 (Fig. 94).

|

| Figure 94. Noyes [Gulf] Service Station (ca. 1940). This typical rural station is shared with a general store and other roadside businesses; the storefront, gas pumps and service bay are modern. |

The later house and house-with-bay station types of the 1920-30s are represented by sites along Route 49 near Dennisville, and on Main Street in Port Norris. The house/office, topped with a gable or hip roof and set behind the pumps, was designed to blend with the local neighborhood. A smaller but more formal example is found in a building relocated to Mauricetown, which the owner believes was a Sunoco station. This small, frame, house type features fifteen-light windows flanking a central door; the roof features molded blue "shingles" and a central eyebrow profile. Today it is used as the Pump House Antiques shop.

An oblong box most accurately describes the service stations built during the Depression, when oil companies used a flat roof and incorporated the service bay into an enlarged office to reduce construction costs. A growing line of automotive supplies occupied the windows to attract customers. This type of station was built as late as the 1960s with some alterations, such as using gable roofs to give the building a quainter colonial look. Many of these station types survive in Salem, Bridgeton, and Millville. [47] Over the years, many early filling/service stations have been preserved by their adaptation to new uses, such as stores or dwellings, while others are empty and derelict.

In tandem with the advent of filling stations are facilities for food and shelter: diners and tourist cabins. The Salem Oak Diner (ca. 1940s, Fig. 95), at East Broadway, is a classic rectangular steel diner, inside featuring counter and booths where patrons enjoyed hearty, convenient and inexpensive food. The few historic lodgings that exist are not surprisingly located at the southerly end of Route 47 as it approaches Cape May. Adjacent to the road, these clusters of small cabins with a central office provided inexpensive lodgings for travelers who were not dependent on public or mass transportation. One or two examples of these early twentieth-century properties remain in place today, though they have been moved, considerably altered, and appear run down.

|

| Figure 95. Salem Oak Diner (ca. 1940s). This classic glass and steel roadside eatery features an especially noteworthy neon oak leaf in its signage. |

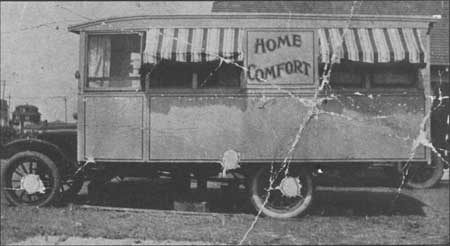

For the traveler who sought the maximum flexibility in automobiling, early recreational vehicles such as this mobile home dubbed "Home Comfort" made excursions to shore resorts such as Sea Isle City as expensive as the gasoline needed to get there (Fig. 96).

|

| Figure 96. Motor homes such as this, owned by Wally Hiles of Millville, were an alternative to motels at many Atlantic resorts. Wettstein, early 20th century. |

Air

The twentieth-century transportation breakthrough of air travel is evidenced on a small but significant scale in South Jersey. In 1940-41, the U.S. Army built the Millville Army Airfield as a defense facility where pilots of P-47 thunderbolts trained; the base is closed, but the representatives of the resident Millville Army Airfield Museum consider it the first designated defense airport. The site (Fig. 97) included standardized barracks, offices, mess hall, movie theater, fire station, and aircraft facilities. Some modern industrial buildings share the old airfield today, as part of the city's industrial park is there.

|

| Figure 97. Millville Army Airfield, built 1941-42. As seen today, the complex of narrow, one-story concrete-block barracks are plain; hangars of corrugated metal are still used. Wettstein, 1990. |

|

| Figure 98. The mosquito was the logo of the World War II airbase as a banded fighter plane. |

The base operated until the end of the war, when the barracks were converted into apartments for veterans and their families. Eventually these structures were let to non-veterans, and after that used as offices. In 1946, after the City of Millville inherited what became a small, regional airport, Francis Hine and Josiah Thompson set up the Airwork Corporation in several of the extant buildings. The business, which dealt with overhauling airplane engines as well as the sale of parts, spurred the arrival of a handful of other small firms that continue to sustain the airfield. [48] The former base is celebrated today by the museum, which has appropriated the base's tongue-in-cheek symbol, the virulent mosquito (Fig. 98).

Notes >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 14 2005 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj2/chap6b.htm

![]()

Top

Top