.gif)

MENU

Chapter 1

Early Resorts

Chapter 2

Railroad Resorts

Chapter 3

Religious Resorts

Chapter 4

The Boardwalk

Chapter 5

Roads and Roadside Attractions

Chapter 6

Resort Development in the Twentieth Century

Appendix A

Existing Documentation

|

RESORTS & RECREATION

An Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Heritage Trail Route |

|

CHAPTER II:

Railroad Resorts (continued)

Barnegat Bay

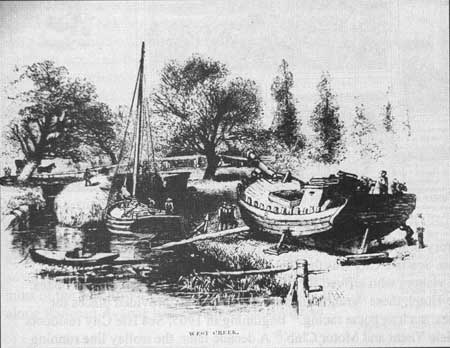

While nineteenth- and early twentieth-century guidebooks speak of most shore resorts as individual cities, the mainland towns from Toms River to Tuckerton are often subsumed under the title "Barnegat Bay resorts." Traffic between New York and Long Branch generated Monmouth County railroad lines, but the shipbuilding and charcoal industries at Toms River and Tuckerton were responsible for Ocean County rail development. The bay towns of Forked River, Waretown, and Barnegat were established communities relying on the products of forest and sea long before the railroad brought resort trade; sportsmen traveling to Tucker's Inn and other area hotels discovered small settlements, not freshly surveyed lots awaiting trainloads of prospective buyers. A year before Kobbe wrote about the Barnegat Bay resorts, a correspondent for Harper's New Monthly Magazine visited West Creek (Fig. 28) and noted that "the traveller who finds it in his time-tables is quite sure not to make the mistake of supposing that it is much of a town, or a mushroom outcome of a real estate speculation." [27] The Harper's reporter bypassed the "inducements" of Long Branch to continue down the coast "in search of the picturesque" aboard the New Jersey Southern Railroad. After transferring to the Tuckerton Railroad (Fig. 29) at Whitings, the reporter and his artist friend traveled to the little village of West Creek between Manahawkin and Tuckerton. A town of fishermen, farmers, and boat-builders who took on other tasks, such as harvesting salt hay and ice when the season permitted, West Creek exemplified the varied economic base characteristic of most Barnegat Bay communities. [28] The railroad provided new markets for oysters, clams, and other products formerly transported over poor roads in wagons. Though bay towns profited from a tourist trade as a result of improved access, locals were more interested in shipping opportunities.

|

| Figure 28. West Creek. Harper's Monthly. 1878. |

|

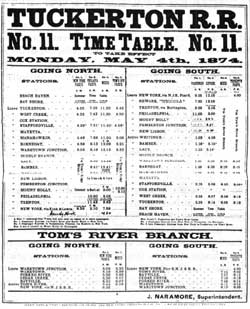

| Figure 29. Tuckerton Railroad Schedule. 1874. |

After discussing the bay's geographical features and the "pirates of Barnegat," Gustav Kobbe reaches the conclusion that "Barnegat Bay is all sport." [29] His account of the rivalry between Forked River, Barnegat, and Waretown for the title of best fishing and gunning grounds describes a different kind of seasonal resort traffic. Fishermen who visited the area throughout the summer marveled over the large numbers of weakfish, sheepshead, and kingfish, while the gunners arriving in the winter and spring expected a plentiful supply of teal, broad-bills, blacks, red-heads, and other birds. The quail, rabbit, raccoon, and fox frequenting the woods were also fair game. Waretown earns Kobbe's highest rating as a fishing ground because of a convenient point of land extending from the salt marsh to the shore within easy access of the railroad station. "Nevertheless, among sportsmen Forked River is considered the fishing headquarters for Barnegat Bay, and Barnegat the headquarters for gunning." According to Kobbe, this preference for Forked River was based on the town hotel, the Lafayette House, run by Sheriff Parker. Not only did the Lafayette offer a plentiful supply of food at early hours, but also quick, efficient stage transportation directly from boat to hotel. Barnegat's favorable situation was based purely on geographical location, its proximity to the chief "shooting points" of Lovelady and Sandy Islands. Low cost was the final incentive in Kobbe's promotion of the area. His list of prices for rental boats, bait, and gunning privileges indicates a well-organized sporting "industry" along the bay in 1889. [30]

Although the Tuckerton Railroad, like the Camden and Amboy, was organized by merchants eager to transport local goods inland, it also promoted resort development. Completed in 1871, the line extended from the Pennsylvania connection at Whitings to Tuckerton, passing through Bamber, Barnegat, Manahawkin, West Creek, and Parkertown. [31] Writing shortly after the Tuckerton Railroad began laying tracks along the shore, Woolman assured his readers that "doubtless the time is not far off when the entire New Jersey shore, from Sandy Hook to Tuckerton, a distance of about 90 miles, will be thickly studded with hotels and cottages, thus affording delightful and healthful resorts to a vast multitude, who in summer abandon the stifling air of our cities and inland towns for the pure atmosphere of the seashore." [32] Within a matter of decades, his prediction would become reality.

A 1920 brochure of the Central Committee of the Barnegat Bay Boards of Trade focused on the area around Toms River. The advertisement promoted the strategic location of the town, exactly between New York and Philadelphia and at the crossing of the Pennsylvania and Jersey Central railroads, and its convenient bay access. The following description is typical of the promotional literature published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, particularly by railroad companies with stations in established resorts:

Toms River has a tang of its own—no other place is quite like it; no other village can take its place; and to those who have once tasted the joys of Toms River and Barnegat Bay, the attractions of the ordinary summer resort are insipid and flat. One season at Toms River remodels a man's ideas of sport and recreation, and two seasons makes Toms River a habit that lasts as long as life itself. [33]

The brochure also lists the healthful benefits of vacations in Island Heights, Seaside Heights, and Seaside Park. Particularly apparent is the emphasis placed on the select group of visitors allowed to enjoy the area. Distinguishing the bay-area towns from those populated by "excursionists," the brochure responds to the growth and corresponding "democratization" of other Jersey resorts such as Long Branch and Atlantic City. Such direct comments on the social composition of the area may have reflected the recent development along the south side of Toms River, primarily the work of speculators from New York and Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania and Long Branch Railroad, which began service to the area in 1881, made the land more appealing to investors, and two years later, Island Heights was popular enough to require a branch line.

North Shore

The Long Branch and Sea-Shore Railroad began building down the coast in 1863, reaching Long Branch two years later on tracks "so close to the ocean beach in some places that the surf blends with the rattle of the cars and the shriek of the locomotive whistle; and at times in high tides, the waves have washed over the track." [34] A little over a decade later, trains were running from Long Branch to Sea Girt and Manasquan in Monmouth County. Meanwhile, the New Jersey and Long Branch Railroad worked its way southward. In 1882, tracks ran from Sandy Hook to Bay Head, where connections were made with the Philadelphia and Camden line of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Traffic along the rails was intense because the New Jersey Southern and Pennsylvania ran on Long Branch and New York tracks. Comparing transportation by mail stage ten years earlier to modern rail travel, an Asbury Park journalist reported that "today fifty-five trains arrive at our station in each twenty-four hours, and all are well loaded." [35] By 1896, reporters announced that "one day last week 776 coaches were used on the New York and Long Branch railroad in transporting people to the seashore. It took twenty-one cars just to carry the baggage away." [36]

|

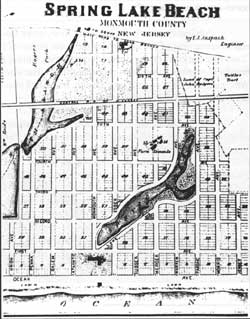

| Figure 30. Spring Lake Beach Plan. Historical & Biographical Atlas. 1878. |

During the 1870s-80s, the arrival of the railroad opened southern Monmouth County to more extensive resort growth. Spring Lake represents the type of land speculation that preceded the railroad. Spring Lake (Fig. 30) was originally four distinct shore communities: Brighton and North Brighton, Villa Park, Spring Lake Beach (named for the fresh-water pond its streets enclosed), and Como, at the north end of the tract. Each settlement grew from one or two large farms into a village centered around a hotel and a railroad station. Undeveloped under a string of owners from the 1760s, the land was subdivided, sold off, and built up during a relatively short time in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The farmland, dunes, and forests adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean between Lake Como on the north, and Wreck Pond to the south, became an urban grid pattern of streets. In 1872, William Reid and John Rodgers, owners of a prominent stagecoach business, foresaw that their enterprise would be rendered obsolete by the coming railroad and converted their farm near Wreck Pond into Rodger's Villa Park and Reid's Villa Park, which were later combined into a single Villa Park. [37]

In 1873 Joseph Tuttle and William Reid subdivided the Walling Farm and established building lots for the future resort of Brighton. The development of the adjacent Spring Lake Beach area in 1874 followed the founding of the "Villa Parks" and Brighton. Philadelphia fisherman and clergyman Dr. Alfonso A. Willits found the area particularly to his liking and decided to purchase the farmland, developing it into a resort property for wealthy Philadelphians. With the backing of the railroad and members of the Sea Girt Land Association, Willits formed the Spring Lake Beach Improvement Company. Philadelphia engineer Frederick Anspach designed a town plan around the Monmouth House Hotel. [38] The elegant building was "233' long, four stories high, with 270 bedrooms, a dining room seating 1,000 guests, and two large parlors overlooking the ocean." [39] It offered modern amenities such as steam-powered elevators and "electric calls" in every room. [40] Guests visiting the hotel when it opened in 1876 were equipped with boats for restful cruises on the lake and shuttled to and from the railroad station in horse-drawn omnibuses. [41]

Publications, such as Camden's New Jersey Coast Pilot, "a journal devoted to the development and advancement of the interests of the coast region of the state," were a forum for promotion by the "land associations" or development companies. Spring Lake entrepreneurs financed the construction of houses to manage as vacation properties. W.C. Hamilton built the five Victorian cottages pictured in Woolman and Rose's Atlas on romantic tree-filled sites. They mirrored the taste of the times, if not the sandy reality of the beachfront. [42]

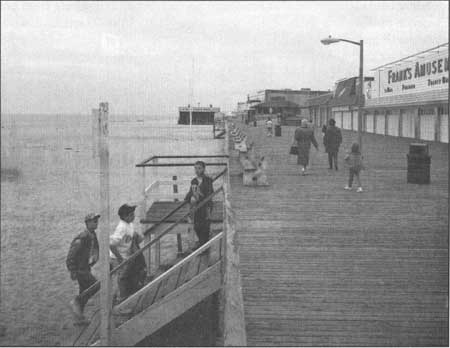

By the 1880s, the railroad entrepreneurs reached Barnegat Peninsula, building railways running much of its length, and linking it to the mainland at Point Pleasant to the north and from Seaside Park via trestle eastward to Coates Point at the mouth of Toms River. Anticipating the construction of Central Railroad tracks across the river, businessmen built the Ocean House along the single road to Point Pleasant Beach. The future city's strategic railroad location at the junction of the major New York and Philadelphia lines made it the ideal location for resort development. Speculators began eyeing the area as early as the 1850s, with at least one unsuccessful attempt to subdivide the undeveloped beach lands into one-acre lots. [43] By 1866, the Oceanfront Land Company bought a bankrupt farm along the Manasquan River. John Arnold, a local sea captain, developed another tract of land named "Arnold City" in three hundred lots measuring 50' x 100'; he included the Atlantic View Cemetery for "the benefit" of his buyers. [44] Three years before the railroad arrived in 1881, Trenton investors organized the Point Pleasant Land Company, planned Point Pleasant City and built the Resort House Hotel. [45] The company laid out streets "in a grid-like Philadelphia plan for easy sales," [46] with lots on both sides of the railroad tracks, reaching all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. By 1890, Edwin Salter could report that "eighteen or twenty years ago Point Pleasant was an unimproved, undeveloped tract. [It] is now seen in fine cottages, schools, churches, stores, hotels and boardinghouses standing on well laid-out streets and avenues, where formerly rabbits and reptiles were want to burrow." [47] An estimated 4,000 to 5,000 summer visitors entertained themselves with promenades along the boardwalk (Fig. 31) and across an iron bridge "lighted with electricity." Point Pleasant's range of accommodations, from hotel rooms at the Resort House to summer cottages for rent each season, rapidly made it one of the most popular summer resorts on the Jersey coast for New Yorkers and Philadelphians. The trolley line between Point Pleasant and Bay Head was completed in 1894, an early sign that the two communities would merge into a continuous settlement. [48]

|

| Figure 31. Boardwalk, Point Pleasant Beach, HABS No. NJ-1012-2. |

Captain Arnold illustrated his faith in the railroad by founding the village of Mantoloking. Bay Head, just south of the point, also became an attractive resort possibility during the 1880s. Though the Central Railroad hesitated to push forward, possibly because of the problems its New York and Long Branch line suffered along the narrow Sea Bright Peninsula, it was encouraged to proceed by the establishment of a Pennsylvania Railroad line. In 1880, a group of visionary Philadelphians convinced of the resort's financial potential, supported the railroad company's line from Pemberton to the shore. [49] Roads were built, with bridges to the mainland, and in the twentieth century, new hamlets filled every inch of land among the towns and even crept out onto Barnegat Bay islands that barely rise above the water line. In the process of this rapid development, much of the natural landscape that initially inspired settlement has disappeared.

Bay Head, at the head of Barnegat Bay, was founded by a triumvirate of Princeton bankers. "The big three rode into town on a summer day in 1877," finding dunes, tall grasses, a pond, the bay, bushes, meadows, marshes, and "the smell of the sea." [50] Edward Howe, William Harris, and David Mount apparently saw opportunity, too, for they bought 45 acres from Capt. Elijah Chadwick and founded the Bay Head Land Company in 1879. [51] The Bellevue Hotel, the first of five big hotels, accommodated visitors by 1881, when the New York and Long Branch Railroad was extended to Bay Head from Manasquan on the north. The Pennsylvania also opened its line from Seaside Park, which connected via trestle to the mainland. Before the new bridge, all supplies had arrived by boat. Almost immediately after the crossing was completed, wood-shingled summer homes were erected along the beach and private estates appeared on the shore of Barnegat Bay. [52]

Bay Head managed to attract the genteel clientele desired (Princeton University faculty and founding bankers) with lots sold under deeds prohibiting everything from beer to slaughterhouses. [53] Evidence of this exclusivity is still visible today, both in street names remembering Princeton professors [54] and rows of well-preserved houses. "Houses at Deal and Elberon or Margate may be bigger and brighter and more costly," says one Jersey Shore chronicler, "but the Bay Head-Mantoloking homes, set comfortably in reasonably well-preserved dunes, are like the etchings of seaside 'cottages' in Harper's Magazine. There is unshowey evidence of wealth, of conservativism—the expensive 'natural' look, the 'Ivy League' look, so to speak." [55]

A contrasting but perhaps fictitious side of Bay Head was recorded in the novel 1919, part of John Dos Passos' trilogy USA. Richard Ellsworth Savage, one of the book's multitude of shallow characters, comes of age working in a local hotel. Savage discovers Christianity at St. Mary-by-the-Sea Church, meanwhile getting involved with the church minister's wife, whom he sees every Sunday night when the minister goes off to preach in Elberon. [56] Dos Passos himself, who apparently visited in 1918, recorded a sunnier outlook in his diary: "Could anything be stranger than the contrast between Bay Head—the little square houses in rows (Fig. 32), the drugstores, the boardwalks, the gawky angular smiling existence of an American summer resort—and my life for the last year. Hurrah for contrast." [57] In Bay Head several stores and an Applegate's Garage opened to serve the locals, but no substantial business district developed, and residents were forced to bring staples from Point Pleasant. The city was connected to Bay Head by a streetcar that ran in the summer between 1903 and 1919. [58]

|

| Figure 32. Elmer Cottage, Bay Head HABS No. NJ-1099-1. |

Mantoloking, adjoining Bay Head to the south, is the name of uncertain Indian origin given to a ritzy seaside summer cottage community planned by New York real estate promoters. Frederick W. Downer began assembling land in 1875, for what was to become a resort based, not on lodging, but ownership. [59] John Arnold organized the Sea-Shore Land and Improvement Company in 1878 and began selling lots for the future city. To attract wealthy buyers, he imported topsoil and offered, on this parched, windswept sliver of land, the possibility of luxurious lawns. [60] Rather than locate a public boardwalk or a street directly at the ocean, as in more populist beach communities like Ocean Grove, the choicest lots were fronted to give privileged buyers the beach and view all to themselves. The large number of shingled mansions still standing, such as 1237 Ocean Avenue, perhaps testify to the success of this formula; some people built cottages complete with carriagehouses, as at 1233 Bay Avenue. [61]

The history of Lavallette parallels that of Mantoloking and Bay Head farther north, having been opened by a land "improvement" company in the 1880s and prospering with the coming of the railroad. It also benefitted from a growth of leisure time in America among the classes to whom it catered—doctors, lawyers, and successful businessmen who, by the 1880s, could afford to buy or build summer homes (Fig. 33) and take time off from work to spend at them. [62] One local builder was Capt. McCormick. [63] Peter Bloom advertised himself as "pioneer carpenter and builder" in 1937. [64] Fire and demolition have destroyed many early buildings, and the automobile has brought a blighted, worn appearance to the city's main street, Grand Central Avenue. "There is little if any discernible concern for preservation in the town," according to the report on Lavallette in the historic sites study of Ocean County. [65] Despite this laissez-faire attitude toward history, much of old Lavallette remains; of particular interest are the Lavallette Hotel on Grand Central Avenue and the Lavallette Theater to the south, whose stucco alterations suggest an effort to streamline and modernize. [66]

|

| Figure 33. Wood-shingled Houses, Lavellete. Photo by Alfred Holden. |

Between 1875 and 1880, the railroad began bringing visitors to the shore communities south of Ocean Grove and Bradley Beach. Speculators anticipating opportunities for land development "followed the tracks" down the shore to Ocean Beach, now known as Belmar. [67] The founders, originally from Ocean Grove, predicted that people would want to move up to larger, more luxurious homes on the Jersey Shore. [68] For $100,172.50 they bought what amounted to a 372-acre peninsula of land bounded by a mile of Atlantic Ocean on the east, and a mile-and-a-half of the lake and inlet formed by the Shark River on the north and west. [69] Operating first as the Pleasant Beach Association and later as the Ocean Beach Association, the founders employed the typical superlatives to entice prospective buyers. "This tract is considered the finest location on the Atlantic Coast, for a summer resort one of the most beautiful landscapes imaginable." [70] In 1875, the 2-year-old Ocean Beach Association advertised half-price lots for hotel builders. The following year, a stage line was established between Ocean Grove and Ocean Beach and a promotional auction was held during one of Ocean Grove's camp meetings to sell lots in the new community. Potential investors traveled on excursion tickets from cities along the Pennsylvania line, which added extra cars for travel to the auction from Philadelphia. The successful scheme resulted in the sale of 135 lots and a record number of passengers aboard the Pennsylvania Railroad, [71] By 1878, Ocean Beach entertained the patrons of five hotels: Riverview House, Colorado House, Neptune House (Fig. 34), Fifth Avenue House, and Columbia House. [72] Twelve 80'-wide avenues were laid out perpendicular to the shore, each block being divided into 50' x 150' lots. Depending on location, these were sold for $300 to $1,500 with deeds requiring buyers to build cottages. [73]

|

| Figure 34. Neptune House, Ocean Beach. Historical and Biographical Atlas, 1878. |

In 1908, another land auction was held for undeveloped property between Belmar and Spring Lake, the future site of South Belmar. [74] The Ocean Grove Park Association occupied offices in Steinbach's Department store in Asbury Park while holding drawings for pianos, tea sets, opera glasses, diamonds, watches, silverware, and ice cream makers to draw crowds before each day's auction that August. The Atlantic Coast Electric Railroad ran streetcars from Asbury Park every five minutes, and prophetically, automobiles brought people over from the railroad station. [75] For a time, the new development was called Ocean Grove Park, perhaps strategically; however, one account claims that the name was adopted because "the property borders on the ocean and because the western end of the tract is covered with a fine grove of Jersey Pine trees." [76] Streets were laid out on an angle from Belmar's grid.

|

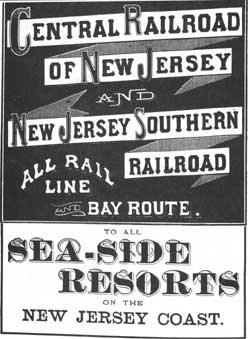

| Figure 35. Label from the Central Railroad of New Jersey. Hagley Museum & Library. |

Kobbe's guidebook explains the shore railroads' complicated history of name changes, mergers and spurs while providing commentary on the scenic view from a train-car window. The Central Railroad of New Jersey (Fig. 35) is preferred over the Pennsylvania line because, "from the start it follows the shore, so that its passengers enjoy many beautiful water views between Jersey City and Perth Amboy." [77] The Central Railroad's Sandy Hook route is an "exhilarating recreation" in itself. As improvements were made in train cars and lines began to compete for the growing number of shore visitors, rail travel became the first stage of a resort vacation, rather than merely the means of transportation.

The Central Railroad's own "Travelers and Tourists Guide to the Seashore, Lakes, and Mountains" promoted extensive shore service and a "comfortable ride on a soft-cushioned seat." [78] The introduction to the Central Railroad guide commented on a new kind of literature developing from early reference directories—the company's annual promotional book. Considered a literary "work of art," the guide described the railroad's effort to attract a particular clientele. The company was particularly proud of its much-lauded Sandy Hook route extending from Atlantic Highlands to Point Pleasant. "This Water and-Rail route is the most delightful way of reaching the seashore, and is generously patronized during the summer months by businessmen and others who sojourn on the coast. It is a favorite with many who appreciate a beautiful sail that is absolutely free from the patronage of objectionable people." [79] A second Central Railroad book, Along the Shore and in the Foothills of 1910, appealed to the successful businessman who might prefer a suburban environment to the noise and hassle of urban life. The railroad hoped that its praise of the family values cultivated in suburbia would increase commuter traffic as well as tourist patronage. [80]

Continued >>>

Last Modified: Mon, Jan 10 2005 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/chap2b.htm

![]()

Top

Top