.gif)

MENU

Chapter 1

Early Resorts

Chapter 2

Railroad Resorts

Chapter 3

Religious Resorts

Chapter 4

The Boardwalk

Chapter 5

Roads and Roadside Attractions

Chapter 6

Resort Development in the Twentieth Century

Appendix A

Existing Documentation

|

RESORTS & RECREATION

An Historic Theme Study of the New Jersey Heritage Trail Route |

|

CHAPTER II:

Railroad Resorts (continued)

Long Beach Island

Woolman did not foresee the potential of settlement along a second piece of "shore" in the middle of the Bay—Long Beach Island. In the early 1880s, residents of Long Beach Island prepared for one of the most dramatic structures to support the shore railroad. The new timber trestle bridge from Manahawkin Meadow to Barnegat City was ready for use in July 1886. Along with the inevitable tourists, the railroad brought loads of gravel for filling in the marshy parts of the island. A spur of the main track ran into nearby Cedar Run, where gravel pits were located in the vicinity of Route 9 and Green Street. The gravel and other supplies passed through the main part of Manahawkin on their way to the island. [81] Ironically, the seeds and grasses from the gravel polluted the island's much touted "pollen-free" environment. [82] Although the Tuckerton Railroad managed the island strip, the Pennsylvania Railroad owned the line that stopped at Barnegat City Junction before heading to Barnegat City (now Barnegat Light) or south toward Beach Haven. The railroad operated until 1935, when dwindling ridership resulting from the new automobile causeway made the necessary bridge repairs too expensive.

By the time the Tuckerton Railroad arrived from Manahawkin in 1886, Beach Haven Yacht Club, Holy Innocents Episcopal Church (Fig. 36), and several new hotels were waiting. According to the New Jersey Courier, the railroad would end the "risk of life upon the ice in mid winter in order to go and come to this old isle of the sea." [83] Up until then, travel to the island had been unpredictable and often dangerous. The security of rail transportation brought continued growth at an even faster pace. In the 1880s and 1890s, more homes were built in the residential area between Bay and Atlantic avenues; many of these Victorian cottages are still standing (Fig. 37). Residents and visitors could play tennis at the yacht club, enter boat races, and participate in events sponsored by the Corinthian Gun Club. Long Beach City (present-day Surf City) grew from out of "the Great Swamp" in 1873, and the extreme north end of the island became Barnegat City in 1881.

|

| Figure 36. Holy Innocents Episcopal Church, Beach Haven, Long Beach Island. HABS No. NJ-1102-1. |

|

| Figure 37. Pharo House, Beach Haven, Long Beach Island. HABS No. NJ-1103-1. |

Convenient, inexpensive rail transportation also bolstered the island's maritime industries, increasing profits from point fisheries at Ship Bottom, and salt-hay and seaweed harvesting. [84] In the 1920s, the Barnegat docks were the site of the first cooperative fishery in America. By 1936, commercial fishing centered around five fisheries—Barnegat City Fishery, Surf City Fishery, Ship Bottom Pound Fisheries, Crest Fishery, and Beach Haven Fish Company. Using boats made on the island, the fishermen pulled in between 6 and 10 million pounds of fish every year. [85] Today, evidence of these early fisheries exists only in the form of docks and sheds at Barnegat Light and Beach Haven. Fishermen share the area with local artists who have converted some of the buildings into Viking Village (Fig. 38), a group of shops and studios. [86]

|

| Figure 38. Viking Village, Barnegat Light, Holden. |

The Trolly

Once tourists arrived at the shore, a different kind of rail provided local transportation. The first electric street railway, constructed in 1887, began at the Asbury Park railroad station and over the next decade traveled north to Deal Lake and south to Avon-by-the-Sea. [87] Residents of Avon welcomed the trolley with a "Railway Greeting" composed for the occasion. "Loud the song of jubilee/Together let us sing/For the march of progress/Like a bird upon the wing/Onward comes the rail car/Electricity is king/Hip, hip hurrah for the railway!" [88] Despite early wiring problems, the Sea Shore Electric Railroad managed to improve its system and set the example for future street-car companies. In 1895, the Sea Shore bought the West End and Long Branch Street Railroad horse-car line and renamed it the Atlantic Coast Electric Railroad. The double-tracked electric line was extended to the Shrewsbury River, where passengers could catch steamboats for New York. [89] A 1908 "Souvenir Book" promoting Monmouth County guaranteed that "the shore can be reached by trolley from any part of the state, Trenton, Newark, Jersey City, and New York City." The brochure assures passengers of "convenient" and "pleasant trolley trips" to all the popular coastal destinations from inland Jersey and New York. [90]

|

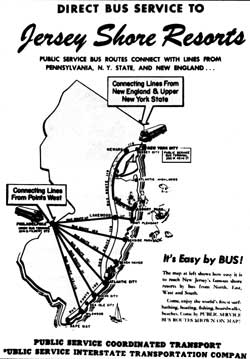

| Figure 39. Shore Resort Bus Service. Sun Fun in New Jersey, ca. 1927. Cape May County Historical & Genealogical Society. |

Though the Central Railroad promised otherwise, in 1910, the railroad was neither free from "objectionables" nor the driving force behind suburban development. The company must have anticipated competition with the automobile, already motoring down roads parallel to the tracks. In the 1920s, the Jersey Central's Jersey City-Atlantic City line offered its response to the threat of vehicular transportation. Suffering from low patronage, the railroad remodeled two engines, painted thirteen cars blue and cream, reupholstered the coach furniture in blue mohair, and provided special meals and other services. Beginning February 21, 1929, the Blue Comet blazed a trail between Jersey City and Atlantic City twice a day. "The 136-mile route ran by way of Elizabethport, Red Bank, Lakehurst, Winslow Junction, and then on to the high-speed Reading Company's Atlantic City Railroad for the final lap to the shore." [91] In 1933, the train's West Jersey rails were incorporated into the recently consolidated Reading and Pennsylvania Railroad. The Comet's luxury travel accommodations were popular in the early 1930s, but by 1939 the company could no longer compete with the growing popularity of automobile travel. The Comet became a shooting star in 1941 when train buffs boarded its cars for a final commemorative trip from Atlantic City.

The 1964-65 Almanac emphasized the "bridge character" of New Jersey railroads by noting that "only 9 percent of the trackage companies serving New Jersey lies within the state, while over 90 percent lies in other states between the Atlantic Seaboard and the Midwest." [92] In the 1960s, the Pennsylvania—the nation's most extensive rail system—offered lines to Sea Girt and Seaside Park, along with its more popular New York and Philadelphia connections. [93] Today, New Jersey Transit provides the only shore rail service, a single line from Jersey City to Bayhead. New Jersey Transit supplements its railroad with bus lines from selected shore stations (Fig. 39) and a variety of special-destination buses from New York, such as the bus to Great Adventure Amusement Park in Ocean County, the Monmouth Park Pony Express from Penn Station to Monmouth Park, and the Victorian Express to Cape May. Advertising itself as an alternative to "the aggravation of driving," New Jersey Transit Authority's "fast, cool and comfortable alternative" continues the long tradition of public transportation to Jersey resorts. [94]

Last Modified: Mon, Jan 10 2005 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/nj1/chap2b.htm

![]()

Top

Top