![]()

Battling for Manassas: The Fifty-Year

Preservation Struggle at Manassas National Battlefield Park

MENU

Appendix V (omitted from on-line edition)

| Manassas

Chapter 10 |

Stonewalling the Mall

Save the Battlefield Coalition

The sense of deception local residents felt deepened as they realized the county would not interfere with the proposed development. Many mall opponents, led by Annie Snyder, swept into action. Snyder had been a fairly quiet participant in the local community for a few years because of health concerns. She had attended the numerous public hearings for the William Center development, but she stayed essentially behind the scenes helping the NWPWCA. The 29 January mall announcement drew her out of semi-retirement and into the forefront of the opposition against the mall. In swift order, Snyder assembled mall opponents at a 5 February public rally held at the Manassas National Battlefield Park. A standing-room-only crowd heard from NPS Chief Historian Edwin C. Bearss, former park historian John Hennessy, members of local organizations opposing the mall, and the former local supervisor who had cast the only vote against the 1986 Hazel/Peterson rezoning. The rally helped establish a sense of unified opposition against what Snyder considered the "raw deal" the county had accepted. [12]

On the heels of this successful rally, Snyder assembled a powerful coalition of preservationists and began making a national issue out of the Manassas mall proposal. She drew on techniques she had learned from Francis Wilshin and had honed in her previous battles. To gain public support, she and her fellow members of the Save the Battlefield Committee, the group that she and Gil LeKander had organized to fight the 1969 national cemetery proposal, put together packets of information about the mall and the battlefield park and sent them to newspapers, concerned citizens, and interested organizations nationwide. She responded to calls from the press and saw her statements published in local papers and such national papers as the Washington Post. Snyder enlisted the help of the Civil War Round Tables and encouraged individual members to write their congressional representatives. She gathered together volunteers who opposed the mall and put them to work stuffing envelopes and circulating petitions. From the petitions, she gained a larger pool of volunteers, who stuffed more envelopes, wrote letters, and held fund raisers. One resident, David Arrington, donated stationery from his print shop. The header, "Rally Behind the Virginians!" accompanied by a silhouette view of the Stonewall Jackson statue symbolized the unified support that Snyder amassed. Soon national organizations and influential individuals began to take notice. [13]

A week after the 5 February rally, Snyder sat at her dining room table with what became the founding members of a national coalition to fight the mall. To take into account this broad base of support, Snyder's Save the Battlefield Committee changed its name to the Save the Battlefield Coalition (SBC). Among those who attended these initial meetings was Tersh Boasberg, a well-respected preservation lawyer and Civil War aficionado. Boasberg laid out the broad outlines of how the group could successfully stall and eventually halt construction of the mall. Soon after the meeting, he obtained the pro bono services of Shea & Gardner, a highly regarded Washington law firm and took legal action against the mall. The most successful tactic for temporarily halting construction involved using the Clean Water Act's requirement to obtain permits before disturbing wetlands. The Save the Battlefield Coalition contended that at least fifty wetlands existed on the William Center tract. Boasberg also established legal contacts with the Department of the Interior, the Environmental Protection Agency, and other federal agencies, forcing them to respond to the coalition's concerns. [14]

Fig. 13. Annie Snyder got her gun figuratively when she took on Til Hazel and his proposal to build a shopping mall next to Manassas National Battlefield Park. (Photo by James A. Purcell. © 1984, The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission) |

While Boasberg initiated legal proceedings, Bruce Craig brought into the fold the first national organization. Craig, who became an ardent supporter of Snyder's work after attending the 5 February rally, went back to the National Parks and Conservation Association (NPCA), where he worked as a cultural resources program coordinator, and convinced its president to make the NPCA the first national organization to oppose publicly the William Center project. Craig then convinced Ian Spatz from the National Trust for Historic Preservation to consider taking on the Manassas mall issue. From these discussions, the National Heritage Coalition formed in mid-May. Sponsored by the NPCA and the National Trust, this organization became an umbrella for Civil War, conservation, historic preservation, military, and other preservation-minded groups. The National Heritage Coalition pooled resources and helped make the Manassas mall a national issue. In the process, the coalition brought preservationists together in a way that had never been achieved in the past. [15]

More people quickly enlisted in the Save the Battlefield Coalition. Jody Powell, former press secretary for President Jimmy Carter and head of a Washington public relations firm, had read the Washington Post's coverage of the mall and had told himself "this sounds outrageous." A phone call from Boasberg, whom Powell had met several months earlier, turned Powell's thoughts into action. Powell brought to the coalition his contacts with the media as well as the expertise to generate interest in the mall. Stories about the plight of the Manassas battlefield park soon rolled off the presses and onto the radio and television airwaves. [16]

When the Manassas mall story went national, it centered on Annie Snyder and her Save the Battlefield Coalition. Snyder's "absolute forthrightness and ability to carry a message" made her a logical focus for the campaign. Her command of theater, including an uncanny ability to cry in public at just the right moment, inspired millions of Americans to consider the emotional side of the issue. For Snyder, the battlefield park was hallowed ground, where soldiers, many of whom were barely teenagers, lost their lives. She wanted to preserve the battlefield as a national park for all time, so that present and future generations could visit it and learn from it. Having the William Center mall so close to the parklands appeared as a real threat to the park's integrity. [17]

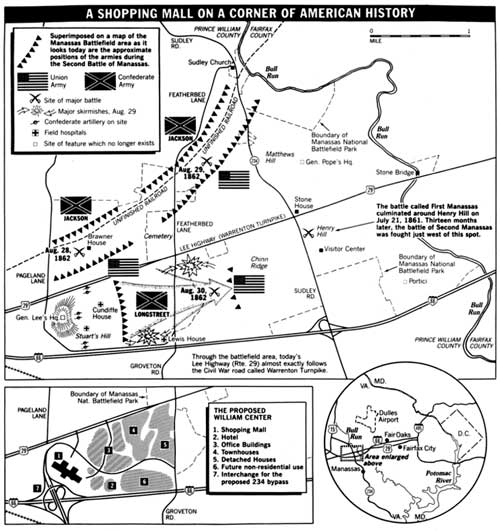

Map. 1. Approximate positions of Union and Confederate forces during the Second Battle of Manassas are superimposed on a map of the existing battlefield park and adjacent land earmarked for the William Center development, graphically illustrating the land's historical significance. (Map by Dave Cook, © 1988, The Washington Post. Reprinted with permission) (click for a larger image) |

Snyder, as well as many prominent historians, had long believed that Stuart's Hill, site of the proposed mall, had enough historic significance to warrant inclusion in the battlefield park. Stuart's Hill had been Robert E. Lee's August 1862 headquarters, where he masterminded one of his most successful battles in the Civil War. Further research indicated that some minor skirmishing occurred on the eastern side of the William Center tract and that unmarked graves may have surrounded a field hospital used during the battle. This information added extra urgency to Snyder's opposition to the mall. Hazel/Peterson Companies hired a Civil War historian, Dr. James A. Schaefer, to conduct a historical investigation of the tract. Schaefer reported in August 1987 that no significant military actions occurred at the site, paving the way for the developer to proceed with construction. In 1988, however, Schaefer reassessed his conclusion and joined the preservationists, saying that it was ludicrous to consider Stuart's Hill as just another one of Lee's headquarters. Schaefer's reversal was prompted by the "keen sense of betrayal" he felt over the mall announcement, which had caught preservationists and the Park Service off guard. These historical opinions strengthened the conviction of Snyder and others that Stuart's Hill and the rest of the tract was hallowed ground and should have National Park Service protection. [18]

Snyder's commitment to preservation of the Manassas battlefields and Stuart's Hill was joined by her wish to save the semirural area where she had lived for forty years. Her farm sat within a few hundred yards of the William Center development, close enough to hear the bulldozers and see the steady construction work. This churning of the earth, particularly around Stuart's Hill, disturbed Snyder greatly. She saw land as a resource, not a commodity. Open space, in her opinion, gave urban populations a place to recreate and commune with nature. Undeveloped land provided ecological benefits to the surrounding communities. She wanted to preserve some of these advantages before unchecked development overwhelmed all of northern Virginia. [19]

Unlike many of her neighbors, Snyder did not believe

that progress in and of itself was beneficial for Prince William County.

She weighed the economic value of a particular development against the

natural resource benefits of preserving the land. In the case of the

campuslike office park Hazel/Peterson had proposed in 1986, Snyder had

resisted pulling out her public relations artillery to fight the project.

She did not welcome Hazel/Peterson with open arms, but she did work

with the NWPWCA to obtain proffers and make the William Center as compatible

as possible with the surrounding landscape. But for Snyder, all agreements

were voided when Hazel/Peterson announced the addition of the regional

shopping mall. The mall represented the kind of unchecked damaging growth

that she had long opposed. For the sake of the battlefield park and

for the sake of the rural countryside embracing the park, she resolved

to fight. [20]

|

History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |