.gif)

|

Research Report GRTE-N-1

The Elk of Grand Teton and Southern Yellowstone National Parks |

|

ELK MANAGEMENT

Regulations

Grand Teton is the only national park where its enabling legislation allows a native wild animal to be killed by state-licensed hunters deputized as rangers. This is provided for under Public Law 787 of the 81st Congress. The provision applies only to elk and to portions of lands added to the original Grand Teton National Park in 1950. The pertinent section of Public Law 787 which relates to the elk is as follows:

"Sec. 6 (a) The Wyoming Game and Fish Commission and the National Park Service shall devise, from technical information and other pertinent data assembled or produced by necessary field studies or investigations conducted jointly by the technical and administrative personnel of the agencies involved, and recommend to the Secretary of the Interior and the Governor of Wyoming for their joint approval, a program to insure the permanent conservation of the elk within the Grand Teton National Park established by this Act. Such program shall include the controlled reduction of elk in such park, by hunters licensed by the State of Wyoming and deputized as rangers by the Secretary of the Interior, when it is found necessary for the purpose of proper management and protection of the elk."

The use of licensed hunters as deputy rangers appears to circumvent an International Treaty for "Nature Protection and Wildlife Preservation in the Western Hemisphere" between the United States of America and 17 other countries (National Park Service, 1968). These contracting governments agreed to "prohibit hunting, killing, and capturing of the fauna and destruction or collection of representatives of the flora in national parks except by or under the direction or control of the park authorities, or for duly authorized scientific investigations.

A permit is required to kill an elk within Grand Teton National Park. The number of permits to be issued each year is determined jointly from studies by Park Service and Wyoming biologists. Permits are requested through the Wyoming Fish and Game Commission's office which furnishes the Secretary of the Interior with a list of licensed hunters. Permits are issued to hunters authorized as deputy rangers at a check station within Grand Teton Park.

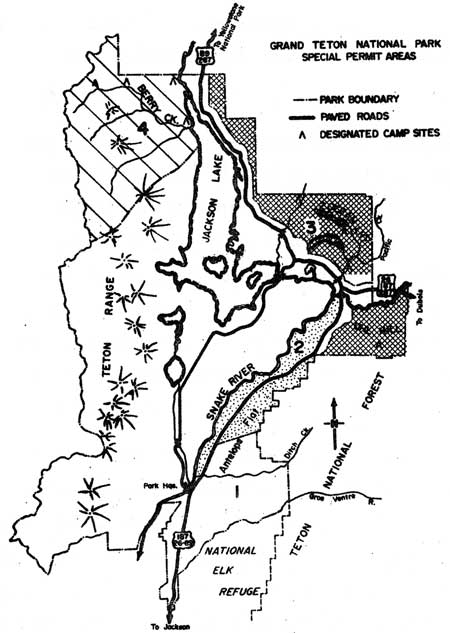

Park hunt units during 1966 are shown on Figure 14. Unit 4 was a roadless mountain area. Roads provided easy access to and through the other three hunt units. Unit 3 was largely foothill terrain with coniferous forests and interspersed parklands. Units 1 and 2 were established as hunt units in 1963. Unit 2 included the eastern side of the forested Snake River bottom, the adjoining open sagebrush-covered benches and during 1965 and 1966, the northern half of Antelope Flat, as shown. Unit 1 included the partially forested Blacktail Butte, as well as extensive sagebrush areas, hayfields, and pasture lands on the southern half of Antelope Flat during 1965 and 1966 seasons. In 1963 and 1964, it also included the northern portion of Antelope Flat.

|

| Fig. 14. Map of park hunt units. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Permits were valid for entire hunting seasons before 1963. In 1963, 1,000 A permits were valid for an October 1 through November 15 period; 1,000 B permits for an October 15 through November 15 period. In 1964, 500 A, 1,000 B, and 1,500 C permits became valid on October 1, 15, and November 1, respectively. The season closed on November 30. In 1965, 1,000 A and 2,000 B permits became valid on October 9 and 30, respectively, and the season ran to December 15. In 1966, 1,000 A and 1,500 B permits became valid on October 15 and November 5. This season closed November 30.

All holders of valid permits could hunt in units 3 and 4. Numbers of hunters in units 1 and 2 were controlled by issuing 50 special permits for each unit by weekly periods or within weekly periods. Special permits were issued to regular permit holders on a first-come, first-served basis, or by a drawing if applicants exceeded available permits. Areas 1/4 mile on either side of main highways and 1/2 mile from buildings were closed to hunting.

Purpose of Management

Public Law 787 specifically restricts the hunting of elk within Grand Teton to ". . . . when it is found necessary for the purpose of proper management and protection of the elk." This "hunting when necessary" restriction was variously interpreted. Reviews of early records and the results from 1962 and 1963 field studies resulted in management problems being defined as follows:

A large herd of elk which summered in Grand Teton Park was migrating to the refuge in October and using forage which should have been reserved for winter periods.

Late migrating herd segments from southern Yellowstone Park, which traveled through roadless wilderness areas before they crossed Grand Teton, had become too large to manage without assistance from park hunts.

Herd segments that migrated through roaded areas east of Grand Teton or summered on the more accessible national forest lands between the two parks had been reduced to levels where they no longer represented the major portion of the elk herd.

This definition of problems led to cooperative management programs which had the long-term objectives of restoring historical elk distributions and migration patterns and reducing the need to hunt elk within Grand Teton Park. Yearly programs after 1963 attempted to (1) restrict early migrations of Grand Teton elk, (2) progressively reduce later migrating Yellowstone herd segments to levels where they could eventually be managed by hunting outside Grand Teton, and (3) allow compensating increases in the herd segments that migrated east of Grand Teton or summered on national forest lands between the two parks.

Hunt Statistics

Yearly and Total Elk Kills by Units

Table 22 shows legal kills of elk in park units open to hunting between 1951 and 1966. Hunts did not occur on park lands in 1959 and 1960. Only units 3 and 4 were open to hunting up to 1962. Yearly kills averaged 189 (27 to 325) animals. The additional use of units 1 and 2 between 1963 and 1966 contributed to increasing the average kill to 670 (612 to 753) animals. Proportion calculations that related known park kills to checked park and other area kills at a State checking station showed park kills ranged from 48 to 73 percent of total kills from the refuge herd during this period. These figures undoubtedly represent increases over previous years.

Yearly kills in unit 4, which was a 49,000 acre roadless mountain area, were comparatively insignificant from a herd management viewpoint. The lower kills in units 1 and 2 in 1966 resulted from an early closing of these areas after a desired kill was obtained from the Grand Teton summer herd. This early closure encouraged hunting in unit 3 where increased kills were obtained from southern Yellowstone Park elk.

| Kill by hunt units |

Percent of refuge herd kill |

Total kills | |||||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Unknown | |||

| 1951-62 (avg.) | 152 | 182 | ---- | ---- | 3 | 189 Avg. | ---- |

| 1963 | 23 | 192 | 164 | 246 | 0 | 625 | 48 |

| 1964 | 17 | 170 | 163 | 398 | 5 | 753 | 61 |

| 1965 | 9 | 208 | 155 | 319 | 0 | 691 | 73 |

| 1966 | 5 | 434 | 70 | 103 | 0 | 612 | 64 |

| Totals | 85 | 2,837 | 552 | 1,066 | 8 | 4,548 | |

1 Park closed to hunting in 1959 and 1960.

2 Season only open in 1952 and 1962 and a 2-year average.

Permit Use, Season Dates and Hunting Success

Applications for Grand Teton elk permits were taken as received until set numbers were reached. Averages from 1961 through 1966 show about 10 percent of the permits were obtained by local residents from within the Jackson Hole area. Other Wyoming residents obtained 80 percent of the permits and nonresidents, 10 percent.

Table 23 lists the dates, numbers of permits authorized and used and hunter success rates for park seasons since 1951. This information shows season starting dates have varied from September 10 to October 20; closing dates, from October 31 to December 15. As will be shown later, the coinciding presence of migrating elk and hunters, rather than season dates themselves, determined total elk kills and hunting success.

Before 1963, an average of 50 percent of the authorized 1,200 to 2,000 yearly permits was used. About 25 percent of the persons using their permits killed an elk. Since 1963, an average of 60 percent of the 2,000 to 3,000 yearly permits was used. Hunting success averaged about 51 percent for 1963 and 1964 and about 37 percent for 1965 and 1966. The lower success after 1964 appeared to result mainly from previously unhunted (since 1951) Grand Teton elk curtailing their early migrations or altering their fall distributions to stay within closed areas west of the Snake River. Some groups of particularly vulnerable resident elk that summered along the east side of the Snake River in what became unit 2 may also have been reduced by the 1963 and 1964 seasons.

| Year | Season dates | Permits authorized |

Permits utilized |

No. elk killed |

Percent hunter success |

Percent kill/total permits | |

| No. | Pct. | ||||||

| 1951 | Sept. 10-Oct. 31 | 1,200 | 510 | 42 | 184 | 36 | 15 |

| 1952 | Sept. 10-Nov. 16 | 1,200 | 455 | 38 | 27 | 6 | 2 |

| 1953 | Sept. 10-Nov. 5 | 1,200 | 568 | 47 | 112 | 20 | 9 |

| 1954 | Sept, 10-Dec. 12 | 1,200 | 600 | 50 | 104 | 17 | 8 |

| 1955 | Oct. 20-Nov. 20 | 1,200 | 624 | 52 | 310 | 50 | 26 |

| 1957 | Oct. 20-Dec. 10 | 1,200 | 748 | 62 | 160 | 21 | 13 |

| 1958 | Oct. 20-Nov. 30 | 1,200 | 583 | 48 | 110 | 19 | 9 |

| 1951 | Oct. 15-Nov. 30 | 2,000 | 1,002 | 50 | 278 | 28 | 14 |

| 1962 | Oct. 1-Dec. 2 | 2,000 | 1,170 | 58 | 280 | 24 | 14 |

| 1963 | Oct. 1-Nov. 15 | 2,000 | 1,194 | 60 | 625 | 52 | 31 |

| 1964 | Oct. 1-Nov. 30 | 3,000 | 1,506 | 50 | 753 | 50 | 25 |

| 1965 | Oct. 9-Dec. 15 | 3,000 | 1,943 | 65 | 691 | 36 | 23 |

| 1966 | Oct. 15-Nov. 30 | 2,500 | 1,615 | 65 | 612 | 38 | 24 |

| Totals | 24,100 | 13,294 | 55 | 4,570 | 34 | 19 | |

About 72 percent of the 1,000 A and 47 percent of the 1,000 B permits were used by authorized park hunters in 1963. In 1964, about 72, 62, and, 44 percent of the 500 A, 1,000 B and 1,500 C permits were used. In 1965, about 69 percent of 1,000 A and 62 percent of 2,000 B permits were used. About 72 percent of 1,000 A and 60 percent of 1,500 B permits were used in 1966. This split permit system was used along with information sheets on elk migration habits to encourage hunters to hunt when elk were present. The A permits which allowed hunting over the entire season were most desired and used by hunters. The B permits, which became valid about 15 to 20 days after a season started, were fairly successful as a management tool after 1963. The C permits used in 1964 appeared to represent a management refinement that could not be used with a limited supply of hunters. These permits were not even fully applied for, despite the use of news and radio media.

Questionnaires were mailed in 1962, 1963, and 1964 to determine the reasons why park permits were not used. Replies for 1962 and 1963 were almost identical. Averages showed about 9 percent killed an elk elsewhere before their permit became valid; 21 percent killed an elk elsewhere after their permit became valid; 32 percent hunted elsewhere; 38 percent did not hunt at all. Replies for 1964, when C permits were used, showed 30 percent killed elk elsewhere before their permit became valid; 8 percent killed elk elsewhere after their permit became valid; 27 percent hunted elsewhere 35 percent did not hunt. The reasons that park permits were not used could be summarized as: approximately two-thirds of these permit holders hunted elsewhere and one-third did not hunt at all. Restorations of elk herds throughout Wyoming have given resident hunters many alternative places to hunt much closer to the State's population centers.

Composition of Kill

Complete or almost complete yearly samples showed averages of 45 percent females, 17 percent calves, 11 percent yearling males, and 27 percent adult males were taken during park hunts from 1955 through 1966. An average of 75 males was killed for each 100 females before 1963; 104 males per 100 females since.

Yearly samples of 568 to 721 elk were aged between 1963 and 1966. Averages of 32, 64, and 4 percent of the male elk older than calves were yearlings, 2-to-7-year-olds, and 8-year-and-older animals, respectively. Comparable figures for females were 15, 66, and 19 percent. The data show hunter selection contributed to the male segment of the population having a younger age structure than the female. About 6 percent of the male elk older than yearlings were 8 years-and-older, as compared to 22 percent of the females. Percentages of 8-year-and-older elk in samples also suggested that sustained high hunting kills after 1963 reduced the proportion of older animals in the elk herd. Eight-year-and-older male elk comprised about 7, 2, 3, and 2 percent of the kill of males older than calves from 1964 through 1967. Comparable figures for female elk 8-years-and-older were 24, 22, 19, and 13 percent over the same series of years.

Evaluation of Management Program

Hunt System

The system of adjusting season dates to coincide with elk migrations, allocating general permits for two or three hunt periods and special permits by weeks for two additional hunt units since 1963 has, in comparison with 1962 (and previous years), greatly increased the efficiency of park elk management programs.

An average of 4 elk per day were killed during the October 1 - December 2 season in 1962; 14 per day during the October 1 - November 15 split A and B permit season in 1963; 12 per day during the October 1 - November 30 split, A, B, and C permit season in 1964; 10 per day during the October 9 - December 15 A and B permit season in 1965; 13 per day during the October 15 - November 30 split permit season in 1966.

Over 75 percent of 280 elk killed during the 2,000 permit 1962 season were taken during October. Large numbers of elk migrated through park hunt units during November, but insufficient numbers of hunters were present to secure significant kills. From 1963 through 1966, split permit periods, later season starting dates and manipulations of hunter numbers in two special hunt units resulted in November kills increasing from 50 to 75 percent of total kills. Total kills ranged from 612 to 753 animals and, in combination with kills outside the park, gave removals that maintained approximately stable herd numbers over the period.

Efficiency of Hunt Units

An average of 13.5 elk (5 to 23) per year was killed in unit 4 over the 4 years between 1963 and 1966 (Table 24). Comparatively few permit holders (20 to 50) appeared to have the desire or equipment to hunt elk in this 49,000-acre roadless wilderness area. The average success rate of 40 percent (25 to 57) was only slightly above that for units 2 and 3 and below unit 1. About 40 percent of the 54 persons killing elk over the 4 years were general public hunters who owned their own pack and saddle horses, about 25 percent were clients of commercial outfitters, and 35 percent were State employees, or guests of employees, who were involved in law enforcement activities within and outside the park. These records, plus results from field studies which showed hunting was not effective in causing movements into adjoining hunt areas (Cole, 1967), indicated that the contribution of unit 4 to the overall management program was small.

| Unit | Elk Kills |

|||||||||||||||

| 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | Numbers of hunters |

Percent Success | |||||||||||

| No. | Pct. | No. | Pct. | No. | Pct. | No. | Pct. | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | |

| 1 | 246 | 39 | 398 | 53 | 319 | 46 | 103 | 17 | 350 | 550 | 630 | 150 | 70 | 72 | 51 | 69 |

| 2 | 164 | 26 | 163 | 22 | 155 | 23 | 70 | 11 | 350 | 550 | 553 | 150 | 47 | 30 | 28 | 47 |

| 3 | 192 | 31 | 170 | 23 | 208 | 30 | 434 | 71 | 444 | 376 | 731 | 1295 | 43 | 45 | 28 | 33 |

| 4 | 23 | 4 | 17 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 50 | 30 | 29 | 20 | 46 | 57 | 31 | 25 |

| Totals | 625 | 7481 | 691 | 612 | 1194 | 1506 | 1943 | 1615 | 52 | 50 | 36 | 38 | ||||

1 Area unknown for 5 kills.

An average of 251 elk (170 to 434) per year was killed in unit 3 over the 1963 to 1966 period. Highest kills were made in 1965 and 1966 when units 1 and 2 were closed during mid-season to direct hunting pressure onto large numbers of migratory elk within the unit. Numbers of hunters ranged from 376 to 1,295, with lowest use during years when the greatest numbers of permits were available in units 1 and 2. The average success rate was 37 percent (28 to 45). This hunt unit obtained kills from the relatively large late migrating segment from southern Yellowstone Park. Plowing snow from roads permitted late season hunting in this unit and adjoining areas outside the park.

Unit 3 appears essential to the management program until the late migrating Yellowstone elk can be controlled by hunting outside park boundaries. This could be accomplished by strategically locating public parking and camping facilities between Grand Teton and the south boundaries of the Teton Wilderness Area, by developing foot and horse trails that bisect elk migration routes, and plowing main access roads as needed.

An average of 138 elk (70 to 164) per year was killed in unit 2. Hunting success for the 150 to 550 hunters using the unit averaged 38 percent (28 to 47). Before 1965, hunters were less interested in this special unit which had only the main highway as its east boundary and dead end access roads leading to river bottom forests along the east side of the Snake River. Adding the north half of Antelope Flat (from unit 1) on the east side of the main valley highway to unit 2 reduced differences in applications for permits and hunting success between the two special units.

An average of 267 elk (103 to 398) per year was killed in unit 1. Hunting success in this extensively roaded unit averaged 65 percent (51 to 72). Numbers of hunters ranged from 150 to 630. The attraction of unit 1, and unit 2 after 1965, appeared to be the opportunity to drive an extensive main and secondary road system, see large groups of migrating elk, and kill an animal in close proximity to a road. Both special units were crossed by Grand Teton elk and eventually by the greater portion of the animals that also migrated through unit 3.

Units 1 and 2, in combination with similar permit hunts on the refuge, have been successfully used to curtail early migrations and reserve winter forage on the refuge; control the size of the Grand Teton summer herd; and during 1963 and 1964, assist in securing greater kills from late migrating elk. With the exception of the portion of unit 2 west of the main through highway, these two special hunt units appear essential to future programs. They should continue to be rigidly controlled by the limited special permit system and only used when desired elk kills cannot be obtained from other units or off park lands.

The use of units 1 and 2 to control the size of Grand Teton's summer herd could be reduced to the extent that additional elk kills were obtained from refuge hunts. The usual combined refuge and special park unit kill quota for this herd was about 400 elk. Only 20 permits were issued for weekly hunting periods on the refuge during 1963 and 1964; 40 permits, during 1965 and 1966. An average of about 90 elk (48 to 133) was killed annually within the 22,700-acre area. This compares with a 405 average for the two adjoining 19,000 and 12,500-acre special hunt units within Grand Teton Park.

Refuge and adjoining Forest Service lands comprised over 37,000 acres. The greater isolation of these lands from main roads and their interspersed tree cover and rough terrain make them a more esthetically suitable elk hunting area than the two special park units which were mainly open sagebrush flats. The use of refuge and adjoining Forest Service lands as hunt units to discourage large groups of early migrating elk from using the southern portions of the winter range 3 to 6 weeks before other herd segments arrive appears essential to future management programs. Separations into north and south hunt units would be desirable. Earlier closing of a north hunt unit (usually the first to second week of November) would allow undisturbed elk to use abundant food sources on their historical wintering areas within Grand Teton and the northern half of the refuge. This would reserve bottomland food sources along Flat Creek for December and later winter foraging. Such patterns of use were reported to occur with early elk herds (Preble, 1911).

Illegal Kills

Known illegal kills of elk and other wildlife in Grand Teton areas open to hunting over a 10-year 1957-66 period totaled 64 elk, 24 moose, 1 mule deer, and 1 antelope (Antilocapra americana). Totals of 118 elk, 5 moose, 3 mule deer, and 2 coyotes (Canis latrans) were known to be killed in park areas closed to hunting during the same period.

Arrest records show not all illegal kills were made by holders of Grand Teton elk permits, but comparisons between years indicated total illegal kills increased in open hunting areas as numbers of permit holders increased. Total illegal kills in closed areas tended to decrease after 1963. This was probably due to intensified law enforcement and previously closed areas, where illegal kills had been high, being opened to hunting.

Conflicts

The illegal kill record for Grand Teton is probably no worse than outside areas where public hunting occurs. It does, however, show that hunting for elk contributed to other park wildlife being killed and violations of closed areas. The illegal kills of elk and other wildlife in closed areas represented the most serious conflict with the primary purpose of Grand Teton National Park which was, in part, to provide visitors with the opportunity to see and photograph native wildlife. Disturbances from illegal hunting or killing of animals commonly caused large groups of elk to leave areas where they were providing outstanding viewing and photography opportunities for park visitors. Roadside moose in areas both open and closed to hunting were either mistakenly shot for elk or for other unexplainable reasons. Actions taken to reduce illegal kills involved distributing informational literature to hunters, conspicuously posting open and closed hunting areas, increasing ranger patrols, and requiring that guns transported through the park be unloaded, cased or broken down.

Comments and letters showed some fall visitors to the park found hunters carrying guns, animals being shot, or other hunting activities on the eastern and northern portions of Grand Teton objectionable. Attempts to reduce this conflict involved prohibiting hunting 1/4 mile on either side of main highways, restricting hunter camps to specified areas apart from visitor campgrounds, using hunt units 1 and 2 (where hunting activities were most visible) only when necessary, and progressively changing the starting dates for park hunts from October 1 in 1964 to October 21 by 1967.

Overall Results

The cooperative management program between Wyoming and the National Park Service has involved coordinating field studies and law enforcement activities, exchanging study information and preparing joint reports, making combined recommendations as called for under Public Law 787, and, after 1963, cooperatively monitoring the overall program designed to restore historical elk distributions and migrations.

The monitoring system used known total park kills and kills checked at a State hunter checking station to calculate the numbers of elk killed in seven different Forest Service areas. These, in combination with park kill figures and migration records, were used to measure in-season progress toward achieving set kill quotas and calculate removals from different migratory segments.

The management objective of discouraging early migrating Grand Teton elk from utilizing winter food on the refuge during October was largely achieved after 1964 (Table 25). An approximate 45,000 elk days of foraging by 2,500 animals from October 14 through 31 in 1962 declined to 200 to 300 elk arriving, but immediately leaving, by 1966 and 1967. The objective of reducing late migrating Yellowstone groups (major portion of north migratory segment) was probably also achieved by the increased November and proportionately higher hunting removals after 1963. This, and compensating increases in herd segments summering on and migrating over lands outside park boundaries, may be shown by the track count differences since 1963 (Table 25).

| Year | Maximum October counts on refuge |

Percent removal north migratory segment |

Percent of total tracks crossing | |

| Grand Teton | Outside | |||

| 1959 | 1,550 | ( Probable ( average ( over period ( 13% or less1 |

---- | ---- |

| 1960 | 2,500 | 58 | 42 | |

| 1961 | 3,500 | ---- | ---- | |

| 1962 | 2,500 | 62 | 38 | |

| 1963 | 728 | 23 | 80 | 20 |

| 1964 | 1,000 | 19 | 75 | 25 |

| 1965 | 375 | 26 | 67 | 33 |

| 1966 | 300 | 17 | 66 | 34 |

| 1967 | 200 | 17 | 43 | 57 |

1 Based upon 1964 calculations, season closing dates and 1959 and 1960 male only seasons (Cole, 1965).

The 1967 track count differences reported by Houston and Yorgason (1968) appeared to result from some migrating groups taking more direct routes to wintering areas instead of converging on Grand Teton Park. This could represent some initial change from behavior adjustments to hunting disturbances, but it may have also resulted from removals of older female elk that perpetuated migration "habits" which previously had high survival value. Some complementary assistance may have also resulted from deferring either-sex seasons, in more accessible hunting areas with low numbers of elk, until the end of the main breeding season (September 21 to October 10). The bugling of adult males associated with harem groups facilitated locating elk groups that would otherwise be difficult to find.

The cooperative program is considered to illustrate that two agencies, with somewhat different responsibilities in public service and philosophies toward land use and wildlife, can effectively work together. A full restoration of elk distributions and migrations to approximate those before 1950 may take at least a decade. A reduction of Grand Teton's role to standby status, with limited hunts when state programs need assistance, may be possible within a few years. Hunting systems on lands outside the park will need to be carefully regulated to retain historical elk distributions and migrations.

Last Modified: Tues, Jan 20 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/fauna8/fauna6.htm

![]()

Top

Top