.gif)

MENU

Methods and Extent of Present Research

![]() Results

Results

|

Fauna of the National Parks — No. 7

The Wolves of Isle Royale |

|

RESULTS—THE TIMBER WOLF AND ITS ECOLOGY

Movements

"The desire to travel appears to be an inherent trait in wolves" (Stenlund, 1955:30). This statement Seems to apply well to wolves on Isle Royale, for they often travel long distances, bypassing areas with high moose concentrations, and sometimes doubling back on their own tracks before making a kill. Kelsall (1957) analyzed 71 wolf observations involving 2,552 minutes, and found that 34 percent of the wolves' time was spent in traveling. Although no such figure was sought during the present study, indications are that Isle Royale wolves probably spend a comparable amount of time traveling.

Much travel seems to be necessary to the island's wolves for locating susceptible prey. Once they consume a carcass, any moose they detect is subject to attack, but before encountering a vulnerable animal, the wolves may travel 60 miles or more (table 8). Burkholder (1959) in Alaska found that distances between kills made by the pack he studied varied from 6 to more than 45 miles, and averaged 24.

TABLE 8.—DISTANCES (MILES) TRAVELED BY LARGE PACK BETWEEN KILLS

| Year | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Number of observations |

| 1959 | 0 | 60 | 30 | 9 |

| 1960 | 10 | 67 | 27 | 11 |

| 1961 | 6 | 44 | 19 | 5 |

| 3 years | O | 67 | 26.5 | 25 |

It is well established that wolves travel where going is easiest. In winter they follow frozen rivers, lakes, and streams; open ridges; and hard-packed drifts. Isle Royale wolves use such features also, but they follow the shoreline most extensively. There the snow is wind-packed, and the footing is good. Travel habits similar to those of the island's wolves were noted by de Vos (1950:174) in wolves on nearby Sibley Peninsula, Ontario:

. . . in late winter and early spring wolves travel extensively on the ice along the shores of lakes. They may either follow the shoreline into bays or cross those in a straight line. Often they run from land point to land point or from one small island to another in the bays around the peninsula.

He concluded that travel routes are determined by topography, distribution of prey, and seasonal changes. Stenlund (1955) stressed the importance of topography, and this factor seems most significant on Isle Royale also.

Isle Royale wolves usually travel single file in winter, especially during overland forays. This appears to be a common habit of wolves, for it has been reported often. Not only is this mode of travel more efficient, but the packed trails that result become convenient overland travelways for the future. Regular use of such a runway keeps it easy to travel despite a heavy accumulation of snow.

Although the wolves commonly use the same trails whenever they pass through an area, they do not have a predictable travel routine. This agrees with work by de Vos (1950) and Stenlund (1955). The island wolves usually do not even follow a circuitous route, although circuits of runways do exist. Most authors agree that wolves follow their circuits in both directions. The Isle Royale animals are no exception, for they often double back on their own tracks.

Established wolf trails are used year after year on Isle Royale, just as they are in other wolf ranges. Many of the trails reported by Cole (1957) were still used during the present study, but less-used side trails varied from year to year. Side trails seem to originate as routes used by wolves in pursuit of moose. Once established, they may be used several times in winter. However, we observed a few occasions when wolves struck out overland without resorting to old trails. Stenlund (1955) also found this in Minnesota. In British Columbia, Stanwell-Fletcher (1942) tracked a pair of wolves which plowed chest-deep for 22 miles in 6 feet of fluffy snow, without lying down to rest.

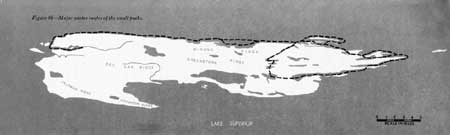

We were notable to follow either the pack of two or the pack of three for more than part of a day, so extensive information on their movements was not obtained. The north shore from Washington Harbor to McCargo Cove probably was the route used most, but a trail was sometimes found from McCargo Cove to Blake's Point and around into Rock Harbor and Moskey Basin. An alternate route from McCargo Cove to Moskey Basin followed the chain of lakes from Chickenbone Lake to Lake Richie. The Minong Ridge from McCargo Cove to Todd Harbor was used often, and the Greenstone Ridge Trail, packed by moose tracks, some times was followed (figure 39).

In summer, wolf tracks and scats have been found frequently on all Park Service trails within the winter range of these packs, so I assume that these trails constitute major summer routes (figure 3). The Minong Ridge and the extensive system of moose trails also are used in summer.

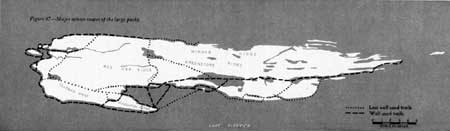

The most-used winter route of the large pack followed the south shore from Washington Harbor to Halloran Lake and Siskiwit Bay, or to Houghton Point, then across Siskiwit Bay (or around its periphery), and along the shore to Malone Bay. From there one route cut across to Siskiwit Lake, Intermediate Lake, Lake Richie, and Rock Harbor; another followed the shore to Chippewa Harbor and then crossed to Rock Harbor (figure 47).

Figure 46—Major winter routes of the small packs.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Figure 47—Major winter routes of the large packs.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Figure 48—Two members of the large pack.

Figure 49—Ten of the large pack file through deep snow.

Figure 50—One member of the large pack runs when author steps out

of nearby shack.

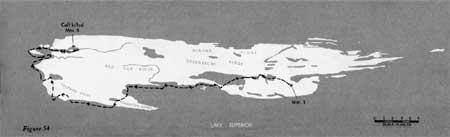

During 31 days, from February 4 to March 7, 1960, when the entire route of the 16 wolves was known, the animals traveled approximately 277 miles, or 9 miles per day (figures 51—55). However, during 22 of those days the wolves fed on kills, and no extensive movement occurred. Thus, in 9 days of actual traveling, the animals averaged 31 miles per day. During the entire study, the longest distance known to have been traveled in 24 hours was approximately 45 miles. In Alaska, Burkholder (1959) followed a pack that traveled a maximum of 45 miles in a day and averaged 15 miles per day for 15 days' travel, presumably including feeding periods. In Minnesota a pack moved 35 miles overnight (Stenlund, 1955).

Figures 51—55—Routes of large pack

February 4 through March 7, 1960.

(click on images for an enlargement in a new window)

The wolves usually travel at a trot, about 5 miles per hour. They rest every few miles, especially on the day after leaving a kill. Generally they leave soon after dawn and begin in summer the large pack continues to use many of its winter routes.

Most lone wolves were seen along routes used frequently by the packs. but, of course, some of these animals may have been strays from the packs. Banfield (1951) also found single wolves following routes used by packs.

Continued >>>

Top

Top

Last Modified: Thurs, Jul 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/fauna7/fauna5d.htm

![]()