Thomas Saladyga Old-growth forests are forests that escaped the large-scale industrial clearing that most of the modern landscape in Appalachia has historically experienced. These forests presently act as a window to glimpse back in time and see what most forests across the Eastern United States would have originally looked like. Natural processes have been the main driver shaping old-growth forests and they often differ significantly in composition and function compared to younger forests. Large, old, charismatic trees and multi-layered canopies are defining features. Decomposing woody debris covers old-growth forest floors. Scientists use old-growth forests as baselines to help manage modern forests. On the Burnwood trail, visitors can see an old-growth forest dating back to the 17th century. Directions to Burnwood TrailFrom Canyon Rim Visitor Center: Take a left out of the parking lot and return to US-19. Carefully cross US-19 into the Burnwood area. Continue up the hill into the Day Use area. The trailhead sign is just before the picnic pavilion. Parking is available in the gravel lot in front of the trailer.

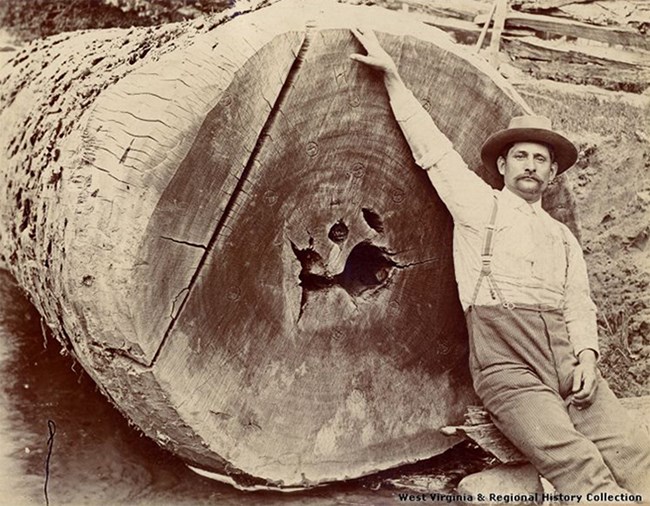

West Virginia & Regional History Collection Stop 1 - Logging History of AppalachiaDirections: From the Burnwood Introduction Wayside, hike roughly .03 miles, or about 70 yards. Coordinates: 38.07632, -81.07547 Large trees over 100 feet tall and hundreds of years old were once common across the Appalachian landscape. Throughout the late 19th to early 20th century, a large-scale commercial logging boom swept across the forests of Appalachia. New advancements in sawmill technology and rapid development of urban areas across the country created a higher demand for lumber, resulting in millions of acres of forests being clearcut within a few decades. It is estimated that less than 1% of the original forests remain throughout the eastern United States and West Virginia, usually in small patches of a few dozen acres or less.

Thomas Saladyga Stop 2 - Defining Old-GrowthDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.01 miles, about 20 yards. Coordinates: 38.07647, -81.07530 What determines if a forest is old-growth? A defining attribute is that an old-growth forest hasn’t experienced any major human disturbance throughout its history. This rule can be hard to adhere to since Native Americans actively managed forestlands across the entirety of North America, and it would be difficult to say no existing forest hasn’t had some human intervention at some point in time. Native Americans frequently used fire to promote wild game habitat and cleared land to build larger settlements along fertile bottomlands. A timeline cutoff frequently used is that a deciduous forest in Appalachia can be considered old-growth if it existed prior to the widespread industrial or agricultural land clearing of the 19th century. The industrial land use era had a large impact across the landscape and the effects can still be seen today throughout the forests that grew back. Forests that predate the industrial era may have had some level of human intervention historically, but enough time has passed so that the disturbance can no longer be observed. In these forests, natural processes have been the major force shaping their development instead of past human impacts.

Aerial footage captured in Google Earth Stop 3 - Forest SuccessionDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.06 miles, about 100 yards. Coordinates: 38.07737, -81.07519 The forest to your right is in stark contrast with the forest along the rest of this trail. This young forest was an old field probably used for livestock, hay, or a yard. Aerial imagery from Google Earth reveals that the National Park Service stopped mowing the field in the mid-2000s and young tulip poplar trees have quickly infilled. Tulip poplars are not tolerant of shade and are quick to establish in open areas with high sunlight, growing vigorously so that other species don’t overtop them. This young forest is an example of a secondary, early successional forest that is in the beginning stages of development. Succession is the process by which vegetation communities change in species composition and structure through time as the ecosystem matures. This forest is considered even-aged, where all of the trees began growing at the same time after mowing stopped. Old-growth forests are late-successional and uneven-aged, where trees naturally grow to their upper age limits and numerous canopy layers and ages of trees can be found. The uneven-age of older forests is evidence that the trees didn’t all begin growing at the same time after a large human disturbance cleared the entire area. Instead, numerous smaller events such as infrequent windstorms knock down a small percentage of trees, creating gaps in the canopy that allow for new growth to establish in pockets throughout the forest once sunlight reaches the ground.

NPS / Chance Raso Stop 4 - Decoding the Old-GrowthDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.04 miles, about 70 yards. Coordinates: 38.07724, -81.07576 You are now in the heart of the old-growth forest. How do we know that the Burnwood forest is old-growth? The presence of numerous species of large trees made park rangers at New River Gorge National Park & Preserve believe that the forest could be considered old-growth. During the fall of 2022, the National Park Service partnered with Dr. Tom Saladyga, Professor of Geography at Concord University in Athens, West Virginia. Dr. Saladyga is a dendrochronologist, or a scientist who specializes in using annual growth rings to accurately date trees and study changes in the environment, such as past fire, climate, storms, and human activities.Dr. Saladyga led eight of his students for a class project to classify Burnwood as an old-growth forest. The work led to a research report published by the National Park Service titled, Documenting Remnant Old Growth at New River Gorge National Park & Preserve: A Pre-Industrial Legacy Forest at the Burnwood Area. The study confirmed that the forest should be considered old-growth. Fourteen of the fifty trees that were sampled were at least 250 years old, with five individuals dating to the 1670s. This research revealed that the forest escaped the industrial logging period of the early 20th century, has experienced minimal human disturbance, and existed prior to European settlement of the New River Gorge.

Thomas Saladyga Stop 5 - Characteristics of Old TreesDirections: Take a left at the intersection to do the loop trail in a clockwise direction. Continue the trail for 0.09 miles, or 150 yards Coordinates: 38.07670, -81.07717 This large chestnut oak is over 160 years old and provides an example of some of the unique physical characteristics trees develop in older age. By looking around the entire trunk, you will notice some parts of the tree’s bark are thick-plated and blocky while some areas of bark are flat. Many older trees will have a mix of balding and protruding bark patterns up and down the entire trunk. Bark on old trees can also be strikingly different in appearance compared to younger trees of the same species. Old trees also have very little stem taper, with minimal change in diameter from the base of the tree to the top near the crown.

Thomas Saladyga Stop 6 - How Tree Age is DeterminedDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.03 miles, about 50 yards Coordinates: 38.07675, -81.07778 The large tree just off the trail to the left with thick-plated, irregular shaped, blocky bark resembling alligator hide is a blackgum. Blackgum is a long-lived, slow growing tree that is highly tolerant of shade, being able to wait in the understory for centuries before a neighboring tree falls and allows for direct sunlight to reach the forest floor. This blackgum is the oldest tree along the trail and has an inner-ring date of 1674, being at least 350 years old.

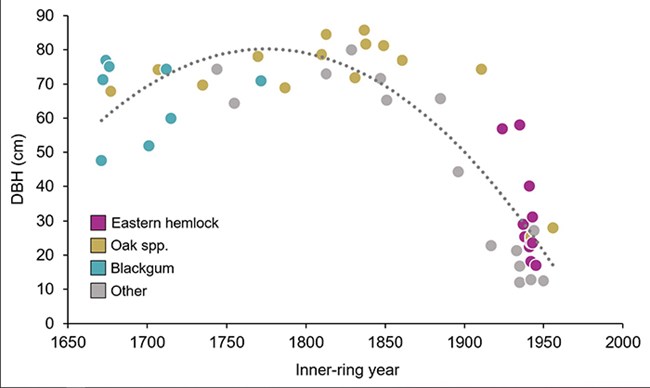

Thomas Saladyga Stop 7 - A Forest GiantDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.07 miles, about 115 yards. Coordinates: 38.07751, -81.07830 This American beech is the largest tree by diameter and volume along the trail. Unfortunately this tree couldn’t be dated due to being hollow, but despite its size it may not be as old as it appears. Some large trees are young, and some small trees are old. While larger trees are usually older, this relationship between size and age will not be as consistent with the oldest of trees. The graph from the study conducted by Concord University researchers shows that the relationship between tree size and age starts to fade once a tree reaches about 200 years old. Oftentimes, the oldest trees are rather small and unsuspecting; the oldest tree in this forest is a blackgum off-trail that dated to 1671 but was less than 19 inches in diameter. Trees like this example have usually been growing under closed forest canopies for long periods of time, waiting for an opportunity to capture sunlight. The large, spreading branches on this American beech indicates that it has been growing in more open conditions free of neighboring trees competing for sunlight, allowing for decades of rapid growth. Two American beech trees smaller than this individual were sampled in this forest, each with inner ring year dates of 1829 and 1755 respectively, and the age of this large tree is probably within that range.

Ricardo Chinea-Pegler Stop 8 – DecompositionDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.14 miles, about 245 yards. Coordinates: 38.07841, -81.07714 There are many different components other than just big, old trees that make up an old-growth forest. Large fallen trees on the forest floor, also called coarse woody debris, are a key feature researchers use to determine if a forest truly is old-growth. When a large tree falls it can take decades if not over a century for the wood to fully decompose. Finding this decomposing debris highlights that humans haven’t altered the forest by taking fallen wood for use. This rotting wood does not go to waste. The decomposition of wood recycles nutrients and carbon back into the forest soils, which act as long-term carbon sinks for greenhouse gases.

Thomas Saladyga Stop 9 - Old-Growth ComplexityDirections: Continue on the trail for 0.12 miles, about 210 yards. Coordinates: 38.07735, -81.07581 This large oak tree fell and took out a few other trees with it during a snowstorm in January 2024. Infrequent disturbance events like storms and low-intensity wildfires that knock over and kill a small percentage of trees within the forest are an important ecosystem process. These fallen trees are not necessarily a bad thing, disturbances like this are part of the processes that add complexity to an old-growth forest.

Mark Strella & Kayla Green Stop 10 - Old-Growth Forest NetworkDirections: Continue on the trail, finishing the loop for 0.05 miles, about 85 yards. After finishing the loop, return up the trail back towards the parking lot the way you came. After the final stop, it is about 0.3 miles hike to the parking lot. Coordinates: 38.07728, -81.07540 On August 4th, 2023, a ceremony was held with over 50 people in attendance to induct the Burnwood Trail into the Old-Growth Forest Network, a national non-profit organization with the goal of dedicating at least one protected old-growth forest open to the public in each county in the United States that can sustain a native forest.

|

Last updated: September 19, 2025