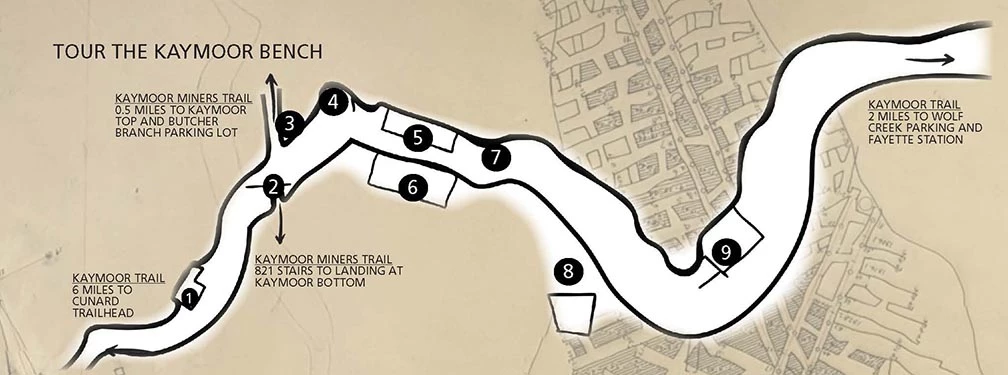

Welcome to the historic coal mining town of Kaymoor. If you are starting from the Kaymoor Top parking lot continue down the Kaymoor Miners Trail for about 0.5 miles to the junction with the Kaymoor Trail. This is a steep hike with about 500 feet of elevation loss. Begin the tour once you reach the small staircase to connect onto the Kaymoor Trail. If you are beginning from the Wolf Creek Parking Lot along Fayette Station you will see the fan house first. The powder house will be first if you begin at the Cunard end of the Kaymoor Trail. This walking tour focuses on the buildings and structures on the bench level of the old Kaymoor mine, this area contained the coal seam, mine entrances, and most of the coal mining operation of Kaymoor. The town of Kaymoor began as a captive mining community for the Low Moor Iron Company of Lowmoor Virginia. Captive in this sense refers to the company owning all aspects of the town from the mining operation to the employee housing, to the company store where employees purchased groceries and other goods. The first 50 homes were built here in 1901 and more homes were constructed in waves over the next two decades. The latest batch of homes built at Kaymoor Top were in a section called “New Town” and some of these homes are still visible along Gatewood Road. The town was separated into three distinct levels. Kaymoor Top (at the top of the gorge) provided housing and a company store for miners and their families. The bench level is the location of the coal seam and the mining operation. Kaymoor Bottom (at the bottom of the gorge) provided more housing, company store, the schools, churches, and the processing plant to sort and load coal onto incoming train cars. Lowmoor turned any coal not used to create power for the town or to heat homes into coke. Coke is a byproduct of coal that is used to produce steel. The Lowmoor Iron Company sold the property of Kaymoor to the Berwind-White Corporation, a large coal company operating as New River and Pocahontas Consolidated Coal Company in 1925. Coal from this mine no longer fueled the 1200 degree smoking coke ovens, it was loaded onto trains and sent to homes and businesses across the country. The mine at Kaymoor continued to produce coal until the coal seams were exhausted in 1965. Once you reach the flat bench area you will be standing in a place that would have been a buzz of activity 100 years ago. Multiple narrow gauge rail tracks crisscrossed this flat area to move the 100s of men and equipment used to extract the sparkling black sedimentary rock that powered everything from homes to battleships. This area helps tell the story of the coal miners and their families who lived and worked here to power the industrialization of the United Staes. Each stop on the tour will correspond to a building along the Kaymoor Trail. Images of each building are included to help orient yourself. Kaymoor is a federally protected historic site and it is important for visitors to do their part in preserving these fragile structures. Walking, climbing, sitting, or standing on historic structures damages them and it is important to practice Leave No Trace principles at historic sites. Do not metal detect, dig, or remove artifacts from this site. Please report any acts of vandalism or theft to a park ranger or local authorities.

1. Powder HouseThis building would have been a storage site for the black powder used to blast coal off the face (walls) in the mine. This is highly explosive, and this stone building would have been away from most other buildings to prevent damage in the event of an explosion. Powder houses were often built of stone even when other mine buildings were made of wood. These buildings needed to be water proof and the heavy iron door would contain the explosion. Mining powder was a combination of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate, also known as saltpeter. Many companies, like DuPont, manufactured several different forms of powder with multiple grain sizes. Smaller grain sizes were used to blast hard rock, and larger grain sizes were better suited for softer rocks like coal. The coarser grains allowed the coal to break from the face in larger chunks (Twitty 2009: 3). Large grains produced a slower explosion because they offered less overall surface area. To denote grain sizes, powder manufacturers used a scale with FFFFFF as the finest, F as medium-small, C as medium-large, and CCC as the most coarse. According to an 1899 King’s Powder Co. ad, sizes FFF, FF, and F were commonly used for coal mining. According to a 1922 DuPont explosives catalogue, “Magazines for blasting powder or sporting powders should be fire-proof and weather-proof. Tests have indicated that ventilation is not necessary in such magazines and that its elimination is a benefit in preventing sweating of the metal kegs.. (La Motte 1922:19). Large scale mine explosions across the country influenced the United States Geological Survey to test what types of explosives would be acceptable for gassy coal mines. Testing began in 1908 and resulted in a list of permissible explosives. Dynamite created an explosion far too large for an enclosed coal mine with soft coal. Instead, an explosive called Monobel was frequently used. Blasting caps contain a powerful explosive that will detonate the rest of a powder charge. They are placed on the end of a safety fuse, and contain a powerful enough explosive to cause powder to explode. Most blasting powders will not blow up even if they are close to an open flame, they will just burn. They need a strong blast of energy to actually explode. Because of this, blasting caps were never stored close to the powder house. Blasting caps are small cylindrical copper tubes used to detonate explosive charges. Blasting caps contain a powerful explosive that detonates the rest of the powder charge. They are placed at the end of a safety fuse and contain a powerful enough explosive to cause the powder to explode. Most blasting powders will not explode even if they are close to an open flame; they will simply burn. They need an intense blast of energy to actually explode. As a result, blasting caps were never stored near the powder house. A form of blasting caps is still used today.

2. Safety Board and SignThe Safety Board and metal sign was installed under the direction of James Ralph Taylor, the Safety Director from the late 40s until about 1954 (Burgess 1983). The metal beam arching across the hiking trail was a constant reminder of company policy for anyone riding on the haulage. Passengers would have exited the car in the wider area of the path to the left of the sign.

The safety board visible by the mine portal was another reminder of company safety policy. Lost Time Accidents for the mining, electrical, and housing departments were displayed separately.

3. HaulageThe haulage transported people and materials from each of the three levels of Kaymoor. The incline was 2200 feet long and extended from Kaymoor Top to Kaymoor bottom. The Hoist House was a large brick building at the top that housed all of the hoist equipment (Burgess 1983). The haulage building had a large wheel and rope to control the system. The rope would unwind and lower the cars and was replaced about once a month. The cars held about 18 people (Dempsey 105). Only one car was connected into this system, and it would make a trip every hour. Bosses or other important positions would have a special button to call the car outside of the hourly trip. About 18 people could ride the haulage at one time. The haulage system to get up and down the hill from top and bottom ran about every hour for non miner residents. During the week the miners would be hauled up and down, and regular people could not ride the haulage during that time. During the week there was a trip at 10:00 ,2:00, and 6:00 for private citizens, called the passenger trip. The other hours of the day were for miners. The stairs you see today follow the original route of the haulage from this bench level into Kaymoor bottom. The stairs you see as you stand under the safety sign were built in 1995. This staircase may be new, but Kaymoor also had a staircase while people lived here. A typical hoistman’s shift was from 6am to 4pm. The Haulage house was relatively close to the housing at Kaymoor Top, so the men would not have to walk very far for their shift. If they forgot their lunch their wives or children could easily bring it to them (Pashion 1985).

The original stairs enabled residents to access the hillside without waiting for the haulage. Some people refused to take the haulage, so they would always use the stairs. The original stairs took a different route than the boardwalk does today. The original stairs would have passed under the haulage tracks and reached the bench level, approximately where the safety sign and mine portal are located to the right. These original stairs were mostly concrete, but there would have been landings and some wooden sections. Claude Elmer built the wooden section of the original stairs. He started as a housing department manager and carpenter. He eventually changed positions and became the outside foreman (OH 279). Portions of the original staircase were concrete. The stairs you see today follow the original route of the haulage from this bench level into Kaymoor bottom.

4. Mine PortalThis gated entrance to the mine would once have allowed men and mine cars to enter and exit the Kaymoor mine. This type of mine, which allowed you to walk in, was called a drift mine. The area you are currently standing in was called the bench, and is the area where the coal seams would have been along the side of the mountain. Most mines had more than one portal, along with more minor “punch outs” for air flow. Small tracks would have allowed mine cars full of coal to exit the mine, and “man trips” to take workers deeper into the mine. A “man trip” or underground personnel carrier, is a form of mine car that transports miners to their working area inside of the mine. These are specialized types of vehicle today, but were typically empty coal cars in the past. The main entrance was similar to a main street in a city, allowing most traffic to enter and exit. Some mines had an entrance for cars to exit the mine and go to the headhouse. Empty cars would then be taken back into the mine through another entrance. Kaymoor would have had four primary entrance portals into the mine. This one you are standing in front of would have been the primary entrance for the locomotive motor cars that pulled mining cars into and out of the mine.

5. LamphouseThe lamp house would store miners’ check tallies and head lamps. Miners would report to the lamphouse at the beginning of every shift to pick up these lamps and return the headlamps at the end of the shift. The headlamps were critical parts of the miners' gear, and the lamps would be ready for someone on the next shift. After the onset of electricity, these lamp houses would have charged the head lamps.

The left side of the lamp house would have been used as the superintendent's office. The superintendent would oversee all mine operations and ensure that everything happened efficiently and safely. Insurance maps of Kaymoor from 1930 show this entire building was being used as an office at that time and was no longer being used as a lamp house.

6. Car Repair ShopThis concrete platform is the foundation of the repair shop that serviced and maintained electric motors used to pull coal cars out of the mine. It also eventually serviced all the electric equipment used in and around the mine. This structure, like many built in the gorge would have cantilevered over the side of the mountain. This platform is easier to see in the fall or winter. In summer it is often obscured by dense foliage..

7. Mine PortalThis gated entrance to the mine would once have allowed men and mine cars to enter and exit the Kaymoor mine. The main entrance was similar to a main street in a city, allowing most traffic to enter and exit. Some mines had an entrance for cars to exit the mine and go to the headhouse. Empty cars would then be taken back into the mine through another entrance. Kaymoor would have had four primary entrance portals into the mine. This one you are standing in front of would have been the primary entrance for the locomotive motor cars that pulled mining cars into and out of the mine. This was the main entrance for miners starting their shift; either day, evening, or “hoot owl.” Miners would have entered here to wait for an electric motor with empty cars to transport them into the mine and their work area. Several portals existed to move coal cars into and out of the mine.

8. HeadhouseThe headhouse of a mine was one of the most important buildings. Loaded coal cars would come out of the mine and come to the headhouse to be dumped. A dock boss would inspect the cars for slate (shale) or other types of rock almost immediately after it left the mine. If there were too many non-coal inclusions, the miner who claimed the car would lose out on that car’s pay. The car would then enter the headhouse, and the weighboss or checkweighman would remove the tag from the car, weigh it, and credit the miner with the weight. The car would then be dumped into a chute that fed into a conveyor. The conveyor would push coal into the main storage bin where it would be held temporarily before being sent to the tipple at the Kaymoor Bottom. The 1,000 foot journey to the tipple happened in a monitor car. The Monitor car system at Kaymoor would propel one full car down the side of the mountain and pull an empty car back to the headhouse. This gravity fed system worked to propel the 8 ton cars by a wire cable attached to a drum at the headhouse. This system could send 30 cars per hour up and down the mountain. Kaymoor’s headhouse was constructed of wood. The conveyor system to transport coal down the mountain was also made of wood until the 1920s. It was then replaced with a haulage system that used gravity to propel two coal cars up and down the mountain. These cars were attached to a chain that was wound around the steel drum at the headhouse. The car full of coal would go down the mountain and pull the empty car from the tipple up to the headhouse.

9. Fan HouseLarge fans were used to create airflow in a mine. This building was built in 1919 during the time of the Lowmoor Iron Company. Earlier versions of this fan house were made of wood, and both burned down. Initially, air was pushed into the mine by a 20-foot-diameter Crawford McCrimmon Fan. This model was replaced in 1908 with a 16-foot-diameter fan. The fan was replaced again in 1910, this time with an eight-foot-diameter Sirocco Fan built by the American Blower Company in Detroit. This Sirocco Fan would have been used when this structure was built and would have remained in use until 1922 (Haer 1986). The arched brick doorway and windows of this building are easily visible along the trail. Portions of the round concrete fan housing are visible if you walk south toward the end of the building and look towards the door.

Fan House Further Down the Trail Towards Fayette StationThis structure was constructed by the New River and Pocahontas Coal Company in 1929 to replace the earlier fan house built in 1919. Portions of the wall are still visible. The three concrete pillars would have held the large fan that supplied air to the interior of the mine. The fan would have been placed in front of the portal to promote air circulation into the mine. The concrete pad would have been for an electric substation. Airflow was crucial for the safety of miners, and companies would conduct regular checks of the air quality inside. This is the first building you will see if you are coming from Wolf Creek on Fayette Station Road.

From Fayette Station Parking LotIf you are beginning the tour from the Wolf Creek parking area along Fayette Station Road, you will be walking along an old service road this mine used to access the bench level. This road was originally built by Lacy Garten, owner of a timber operation. The New River and Pocahontas Consolidated Coal Company finished this road. One of the first things you will notice will be the waterfall along the walking trail. Wolf Creek Falls is the cascade in the creek below the walking bridge. The mossy waterfall along the trail does not have an official name. This water is actually coming out of the Kaymoor 2 mine. The mines at Kaymoor 2 and Minden were connected underground in 1942 to divert this water. According to an employee of the company, “engineers conceived the idea of cutting the two [mines of Minden and Kaymoor] together and use Kaymoor as a drainage way.” This water drains out of a drain way into Wolf Creek below. The Kaymoor Story Continued:Kaymoor Main PageCoal Mining Methods at Kaymoor Coke Production at Kaymoor Living in Kaymoor After the Coal Town References |

Last updated: September 12, 2025