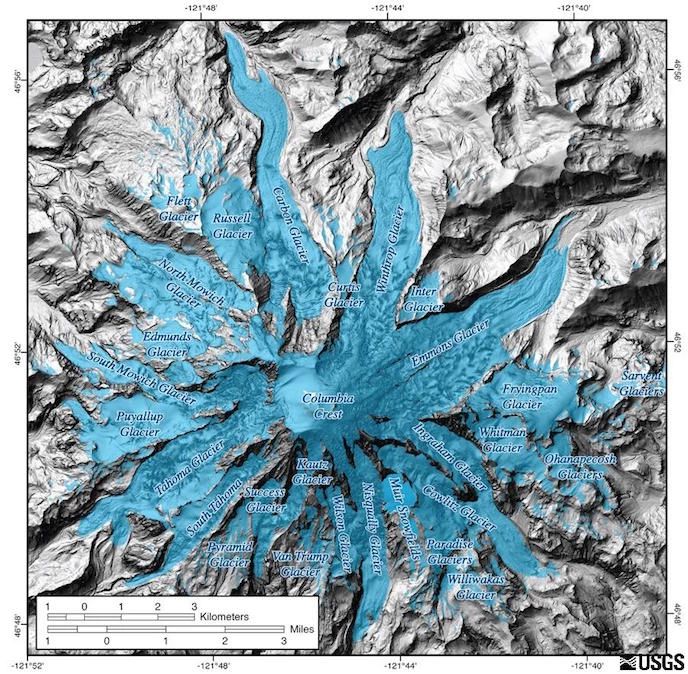

USGS/Tom Sisson Image. Mount Rainier has 28 named glaciers, plus numerous unnamed snowfields. Learn more about the major glaciers below (in clockwise order around the mountain, starting with Carbon Glacier in the north):

NPS/Loren Lane Photo Carbon GlacierCarbon Glacier has the lowest terminus of any glacier in the contiguous United States. By area, it is the third largest glacier on Mount Rainier. Furthermore, it has the largest volume of any glacier on the mountain, a product of its unusual thickness. While most glaciers on the mountain have advanced and then retreated a mile or more, Carbon Glacier exposed only a half mile of deglaciated terrain between 1760 and 1966. This behavior and its thickness are the result of two factors: first, the glacier is well shaded because it is located on the north side of the mountain and surrounded by steep valley walls. Second, the lower end of the glacier is well insulated by rock covering. Both factors reduce melt rates. During one episode in the last major ice age, Carbon Glacier probably flowed into the Puget Sound and merged with the Puget lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Viewing Carbon Glacier: You can see the glacier from several vantage points along the Carbon River trail. From the park entrance at Carbon River, hike or bike along the Carbon River Road (closed to vehicles) to Ipsut Creek Campground. From the campground, walk approximately 3.5 miles (5.5 km) to see the glacier terminus. Continue up the trail an additional 3 miles (5 km) to Moraine Park for an impressive view of the upper glacier.

NPS Photo Winthrop GlacierWinthrop glacier is located on the northeast side of the mountain, just west of Burrough's Mountain. It is the second largest glacier on the mountain, extending from the summit to the 4,700 foot (1,400 m) level of the West Fork of the White River. Its terminus is obscured by a thick coating of rock. Further up the glacier are a series of ice domes formed by ice breaking over bedrock, creating numerous crevasses. During the Evans Creek glaciation of the Pleistocene epoch (22-15 thousand years ago), Winthrop Glacier extended 14 miles (22 km) north of the summit, where it merged with several small glaciers from tributary valleys north of the mountain. By the late 1800s, the glacier had retreated nearly 3.7 miles (6 km) to its current position. Viewing Winthrop Glacier: You can see Winthrop Glacier from the Sunrise area of the park. From Sunrise, you can hike to the glacier along the Wonderland Trail.

NPS Photo Emmons GlacierEmmons Glacier has the largest area of any glacier in the contiguous United States, although the Carbon Glacier has a greater volume of ice. The glacier descends from the summit into the White River Valley. Much of its lower surface is covered with rock debris that originated from a December 1963 rock fall off Little Tahoma peak on the glacier's south flank. The floor of the White River Valley is covered with rocky debris, indicating that the Emmons Glacier during the Pleistocene epoch was nearly 40 miles (60 km) long. Moraines in the valley indicate that the glacier was nearly 1,000 feet (300 m) thick near the White River Campground. Viewing Emmons Glacier: From the Sunrise Visitor Center, follow the 0.2 mile (0.3 km) trail to Emmons Vista to view the glacier. From White River, follow the trail leaving the campground approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) to the Emmons Moraine Trail junction. The trial leads along the edge of the moraine and has excellent views of the terminus of the glacier.

NPS Photo Cowlitz and Ingraham GlaciersCowlitz and Ingraham are two glaciers that share a common terminus. Separated by a rocky ridge named Cathedral rock, the two glaciers merge at the 6,700 foot (2,200 meter) elevation to create a single stream of ice that flows down into the Middle Fork Cowlitz River valley. Below the ridge, a ribbon of rocky debris called a medial moraine produces a dark streak in the middle of the glacier. Further down the glacier are a series of concentric debris-covered ridges called ogives. More than 35,000 years ago, the ancestral Cowlitz Glacier merged with several other glaciers to become a single stream of ice that flowed nearly 62 miles (100 km) from the mountain's summit. By the end of the Little Ice Age, a little over a 100 years ago, the glacier had retreated to within 5.9 miles (9.5 km) of the summit. By 1994, the longest segment of the glacier was less than 4.4 miles (7 km) long. Viewing Cowlitz and Ingraham Glaciers: These glaciers can be viewed from the top of Panorama Point or from along the Skyline Trail in the Paradise Area. Alternatively, a pullout at Backbone Ridge along Stevens Canyon Road provides views of the south-facing slopes of Mount Rainier, with the Cowlitz, Ingraham, and Paradise Glaciers visible.

NPS, Anne Spillane Photo Paradise-Stevens GlacierNearly a century ago, one of the main attractions in the park was the Paradise-Stevens Glacier area. At that time, Paradise-Stevens Glacier was riddled with ice caves and crevasses and was within easy walking distance of major roads. An 1896 map of the glacier places its terminus within 0.6 mile (1 km) of Sluiskin Falls. However, by the 1970s the glacier area had decreased to less than 50% of its 1896 area and separated into two small segments of stagnant ice (glacier ice no longer in motion). The rapid melting of the ice left behind a large area strewn with boulders and rubble carried by the glacier and its meltwater streams, providing visitors with an uncommon opportunity to observe the rock features at the bed of a glacier. Viewing Paradise-Stevens Glacier: From Paradise, take the Skyline Trail to enjoy views of the Paradise-Stevens Glacier.

NPS Photo Nisqually GlacierNisqually Glacier is perhaps the most visited and best surveyed glacier on Mount Rainier. Due to easy access and its prominent location near Paradise, the glacier has been studied since the mid-1850s. In 1857, Lt. August Kautz crossed Nisqually Glacier during an attempt to climb the summit. In 1884, Allen Mason photographed the glacier for the first time, laying the foundation for a photographic record of the Nisqually Glacier that spans over a century. During the 1930s, Tacoma City Light Department and the U.S. Geologic Survey (USGS) began a series of measurements of glacial surface elevation to determine the impact of the Nisqually Glacier's retreat on water supplies for hydroelectric power production. USGS and park scientists continue to regularly survey the glacier today. The product of this research is a record of Nisqually Glacier change spanning nearly 150 years. During this time the glacier has retreated and advanced several times, though the general trend has been retreat. In 1857, Kautz wrote in his journal that the terminus reached a narrow rock channel located underneath the present Glacier bridge on the road to Paradise. By the time Mason began photographing the glacier, the terminus had retreated up the valley 0.2 miles (0.3 km). Photographs taken early in the 1900s show national park visitors posing near the bridge with the glacier clearly visible over their shoulders. By the 1950s, such photographs were not possible since the glacier had retreated nearly 1.2 miles (2 km) up past a curve in the valley and was lost from view to anyone on the road. An advance in the glacier a few years later made it once again visible from the bridge for a short time. However, by the 1970s the glacier had resumed its retreat and again disappeared from view. Since that time the glacier has gone through a series of minor advances and retreats. Viewing Nisqually Glacier: The best views of the glacier are from the Nisqually Vista Trail in Paradise, which starts from the lower parking lot.

NPS Photo Kautz GlacierKautz Glacier is located immediately west of Nisqually Glacier on the mountain's southwestern flank. Beginning at nearly 13,100 feet (4,000 m), the glacier extends less than 2.5 miles (4 km). Although the Kautz Glacier is one of the smallest on the mountain, it is a significant player in the recent geologic history of the park. Twice during the last century the Kautz Glacier was the cause of major debris flows. In October 1947, water abruptly drained from underneath the glacier, ripping away a section of glacier over 1 mile (1.2 km) in length and gouging a 320 feet (100 m) deep canyon into the valley once occupied by the ice. Downstream the water mixed with rock, trees, and other debris to form a fast moving slurry that flowed across the park road almost 6.2 miles (10 km) away. In August 2001, water bursting from Kautz glacier produced a debris flow that flowed over a ridge and into Van Trump Creek. Viewing Kautz Glacier: The best views of Kautz Glacier can be found at Mildred Point. To reach the point, take the Comet Falls trail, which starts from the small parking lot along the Nisqually-Paradise Road just west of Christine Falls. Follow the trail past Comet Falls to reach the junction with the trail to Mildred Point.

NPS Photo South Tahoma and Tahoma GlaciersSouth Tahoma and Tahoma Glaciers are separate glaciers that were connected in the recent historical past. Presently, South Tahoma Glacier flows from a cirque into the Tahoma Creek Valley. Near its terminus the glacier becomes a stagnating mass of ice covered by rock that is nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding moraine. Tahoma Glacier flows from the summit as a single stream of ice before splitting into two lobes that empty into Tahoma Creek and Puyallup River valleys. Between 25,000 and 15,000 years ago the Tahoma and South Tahoma Glaciers were connected, forming a tributary to the ancient Nisqually Glacier. The two smaller glaciers were again connected during the Little Ice Age about 100 years ago and remained so until nearly the middle of the 1900s. Like other glaciers on Mount Rainier, South Tahoma produces periodic and sudden catastrophic floods. In August 1967, water stored within the glacier burst from the glacier surface at the 7,000 feet (2,133 m) level. This sudden flood severed the lower glacier into two halves and then mixed with rocks, mud, and trees, forming a debris flow that destroyed the former Tahoma Creek Campground. Since 1967, at least two dozen glacial outburst floods have undercut ice-laden moraine and formed debris flows that rushed down the Tahoma Creek valley, destroying trails, roads, and the former Tahoma Creek Picnic Area. Viewing South Tahoma and Tahoma Glaciers: One of the best areas for viewing Tahoma Glacier is from the crest of Emerald Ridge along the Wonderland Trail. South Tahoma is best viewed from Indian Henry's Hunting Ground.

NPS Photo Puyallup GlacierPuyallup Glacier begins high on the mountain in Sunset Amphitheater, a large open basis immediately below the summit. Currently the glacier ends in a hanging valley at the head of the North Puyallup River valley. During seasons of above normal snow accumulation in the Amphitheater, a large ice bulge forms and begins moving down the glacier. When it does so, the terminus advances to the edge of the hanging valley. One such wave in 1960 produced numerous crevasses in the upper part of the glacier. By 1962, the ice in the upper glacier was smooth again while the terminus had advanced, covering rocks that had previously been exposed. Fifteen thousand years ago, Puyallup Glacier was joined to South and North Mowich Glaciers forming a single ice mass. The farthest advance of the Puyallup Glacier in recent history occurred around 1840, when it flowed well over the edge of the hanging valley. Viewing Puyallup Glacier: One of the most impressive views of the terminus of Puyallup Glacier is from Klapatche Park. Hike/bike Westside Road (road closed to vehicles at Dry Creek) to the St. Andrews Trailhead. Hike the trail 2.5 miles (4 km) to reach Klapatche Park.

NPS Photo North Mowich GlacierNorth Mowich Glacier lies at the headwater of the North Mowich River, a major tributary of the Puyallup River. The main mass of ice begins at the 10,000 foot (3,050 meter) level and flows down into the North Mowich River Valley. Additional ice joins the main glacier from the south, avalanching down from the Jeannette Heights area. Surveys in 1994 found that the glacier had retreated well over a kilometer up valley compared to its 1898 location reported by geologist I.C. Russell. Viewing North Mowich Glacier: Located on the northwest slopes of Mount Rainier, the North Mowich Glacier is one of the most visible glaciers from the Seattle-Tacoma area. From Mowich Lake, take the trail connecting to the Wonderland Trail and hike to Spray Park for excellent views of the glacier.

NPS Photo Summit Crater GlacierThough most ice in the summit region flows to large glaciers below, some is confined to the crater at the mountain's summit. The crater, produced by recent volcanic eruptions, is a depression into which snow falls and is converted to ice. Since the crater tilts to the east, some ice and meltwater does flow into the Cowlitz-Ingraham watershed. However, much of the ice loss is caused by high ground temperatures that melt the ice, producing a maze of steam-riddled snow caverns. Climbers have often taken refuge from storms by descending into the caves from entrances along the crater rim. Geologist Eugene Kiver and Martin Mumma mapped over a mile (1.2 km) of passageways and found a network of tunnels at slopes of 30 to 40 degrees. Geologist Paul Kennard used radar to determine the thickness of Summit Crater Glacier and found it to be about 200 feet (60 m) thick. Additional References: Driedger, Carolyn. "A Visitors Guide to the Mt. Rainier Glacier". Longmire: Pacific Northwest National Parks and Forests Association, 1986. Print.

Glacier Features

Learn about the unique features and formations created by glaciers and glacial forces.

Aggradation

Aggradation, the process of rivers filling with rocky debris, can play a big role in flooding and other river behavior.

Carbon River

Explore the history and geology of the Carbon Glacier, and how it changes the landscape of the Carbon River area. |

Last updated: March 20, 2025