Photo by Jane Carlson/NPS

Overview

The parks of the Gulf Coast Network are ecologically diverse, isolated, and imbedded in a landscape known for its short geological history and rapid rate of change. The region straddles both temperate and subtropical climatic zones and includes islands, shorelines, floodplains, and rolling hills. Because many different zones converge in this region, its parks often have high biodiversity in plants, birds, reptiles and amphibians. Yet the integrity of park ecosystems and natural resources are potentially threatened by several landscape-level forces. For example, network parks are generally small and unconnected to other habitat patches within altered landscapes experiencing rapid human development. Additionally, the region experiences frequent extreme storm events that have widespread effects on both environments and biota. These factors pose a strong collective challenge to park resource managers and the Gulf Coast Network monitoring program. The network is also challenged to document and monitor the diverse plants, animals and processes that make up each park ecosystem, with many of these entities being relatively unstudied.

Photo by Whitney Granger/NPS

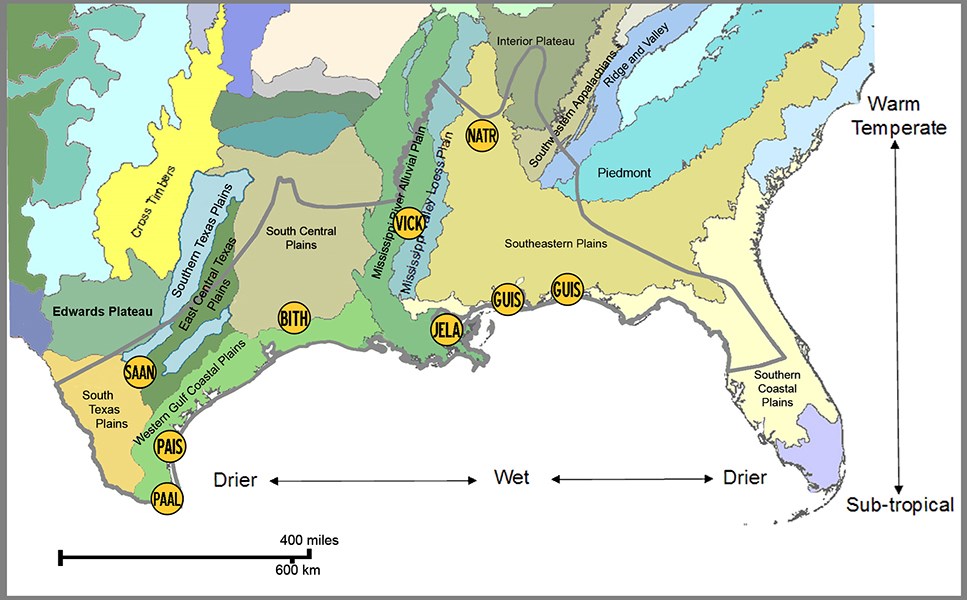

Geology and Ecoregions

The generally flat Gulf Coast landscape formed as a result of changes in sea level during the past 125 million years. Rising and falling sea levels, along with sediment-carrying water flowing in rivers, repeatedly eroded and built up land. The resulting combination of alluvial plains, shorelines, and the most extensive wetlands in the United States host a diversity of ecosystems. The eight network parks are distributed across six ecoregions of the south-central and southeastern United States:

-

East Central Texas Plains: San Antonio Missions National Historical Park (SAAN)

-

Western Gulf Coastal Plains: Palo Alto Battlefield National Historical Park (PAAL), Padre Island National Seashore (PAIS), and Big Thicket National Preserve (BITH)

-

Mississippi Alluvial Plain: Vicksburg National Military Park (VICK) and Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve (JELA)

-

Mississippi River Loess Plain: Vicksburg National Military Park and Natchez Trace Parkway (NATR)

-

Southern Coastal Plain: Gulf Islands National Seashore (GUIS)

-

Southeastern Plain to Interior Plateau: Natchez Trace Parkway (NATR).

Follow this link to access each park's geologic inventory report, where you can learn more about the region's unique geodiversity.

Despite the region’s limited elevational change, biological diversity is high, with striking habitat turnover both within and among individual park units. Many parks contain regions of upland, lowland and coastal physical landscapes and exist at or near the climatic convergence point between the temperate and subtropical zones. This unique location makes the Gulf Coast region and its parks a center of biodiversity of great national value and interest.

Back to top of page

Photo by NPS/GULN

Climate

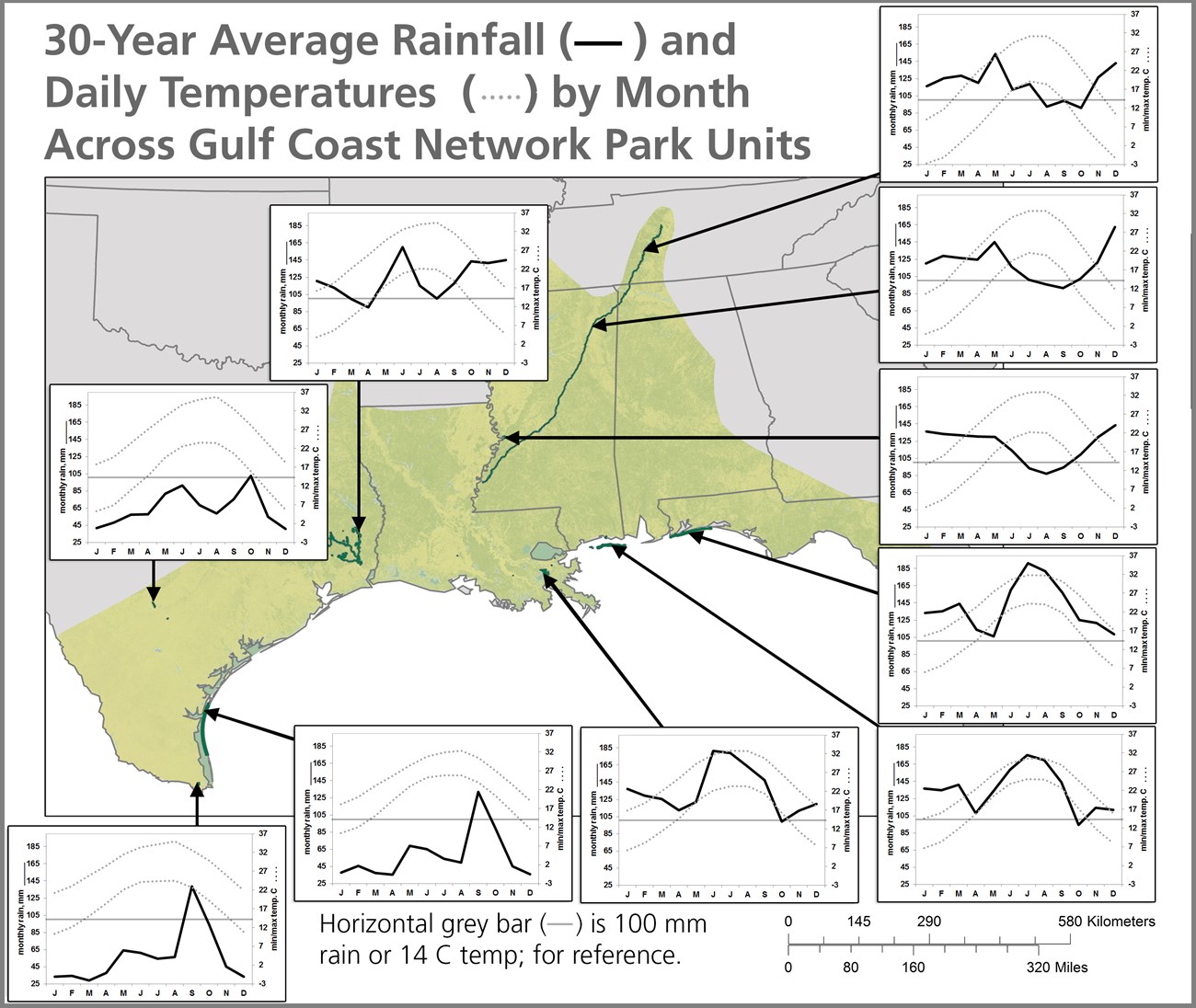

The Gulf Coast climate results from the interplay of global factors, including the El Niño/Southern Oscillation, and regional factors—specifically, its latitude and the influence of nearby oceans. El Niño years are typically characterized by lower temperatures in winter and spring and increased winter rainfall in the Gulf Coast. Fall and winter seasons are typically warmer in La Niña years, especially in Louisiana, followed by little change in spring and higher temperatures in summer. La Niña events are also associated with regional drought conditions, such as those that occurred in the central and western Gulf Coast from 1998 to 2000. Further, El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) has a strong influence on the number of Gulf Coast hurricanes. During La Niña events, the average number of hurricanes coming ashore is typically higher than during El Niño or non-ENSO years.

Data are 30-year normals (1981-2010) from http://www.prism.oregonstate.edu/normals/

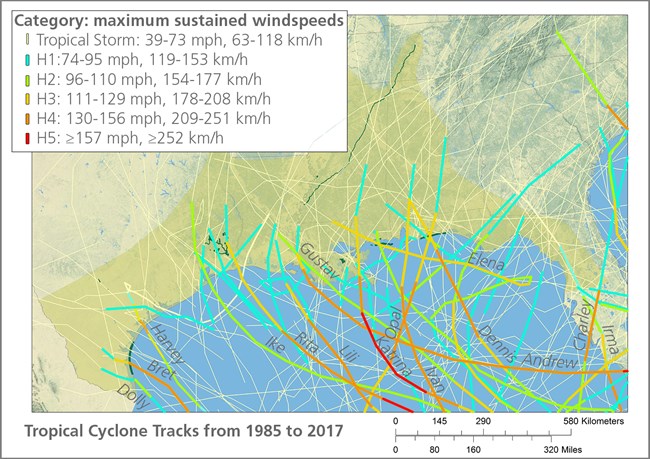

Data are from: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/ibtracs

The Gulf Coast climate is uncharacteristically hot and humid for its latitude, which typically hosts warm, arid, and semi-arid climates. The proximity to major waterbodies influences the region’s climate and its high frequency of hurricanes. Winters are generally mild due to the Gulf's moderating effects. Occasionally, however, these mild winters are punctuated by cold air masses reaching far south from the northern Pacific or the Arctic, bringing low temperatures and freezing conditions. Summers in the region tend to be hot and humid. The adjacent waters of the Gulf and the Atlantic are also major sources of atmospheric moisture, resulting in greater rainfall than is typical for its latitude. Rainfall is brought to the region by a variety of processes, including storm fronts and thunderstorms in the winter and spring, and tropical storms and hurricanes in the summer or early fall. Hurricanes and tropical storms exert major influences on biota, geomorphology, and environmental conditions along the northern Gulf. The shapes of coastlines and islands are changed by these events, which then can alter plant diversity and distribution. Although the effects of these storms are usually thought of as coastal phenomena, the disturbances they cause extend far inland as the systems track to the north. This can be seen in the regional map of tropical cyclone tracks from 1985-2017 above.

Ecosystems

The eight parks in the Gulf Coast Network represent and host important examples of a broad range of ecosystems. Functionally, these ecosystems can be partitioned into three major groupings:1. Uplands

2. Freshwater wetlands and freshwater aquatic ecosystems, and

3. Coastal and near-shore-marine ecosystems.

Within these groups, there are finer divisions based on the dominant vegetation structure, as described below.

Photo by Jane Carlson/NPS

Uplands

Upland ecosystems can be forested to varying degrees, and in the Gulf Coast region, they may not be particularly high above sea level. A defining feature is that soils do not flood or flood only very infrequently. In Gulf Coast Network parks, naturally-vegetated upland habitats typically grow trees in moister climates, but they may be dominated by shrubs or grasses in the region’s drier reaches. The four major classes of upland habitats are forested uplands; woodlands and savannah (25-60% canopy closure); shrublands and grasslands.

Forested Uplands

Upland forests in the Gulf Coast Region range from lower-diversity pine forests to higher diversity mixed hardwood forests. These forests may be on a relatively flat, well-drained soils, as for dry flatwoods, or on slopes, hilltops or rolling hills. Big Thicket National Preserve has large tracts of upland forests with overstories largely dominated by oak species, pine species or a mix including other hardwood species. Elevation in this habitat is important determinant of forest community type. The Natchez Trace Parkway also has large forested units, notably Rocky Springs, Jeff Busby, Colbert Ferry, and Meriwether Lewis. Many tree species co-occur in these forests, including broad-leaved deciduous species (e.g., cherrybark oak, water oak, white oak, southern red oak, willow oak, black oak, post oak, sweetgum, pecan) broadleaved evergreen species (southern magnolia) and pines (loblolly, shortleaf).The loessal bluffs of Vicksburg National Military Park make for an extremely distinctive and highly erosional landscape. The steep slopes in this park grow a mix of hardwood species.

Photo by Jane Carlson/NPS

Woodlands and Savannahs

Woodlands and savannahs are defined as having sparse tree canopies (25-60% closure) and typically a species-rich herbaceous layer. Pine savannahs, most notably of longleaf pine, were once fairly common in the Gulf Coast region, although their geographic extent is now considerably reduced. Upland examples are called flatwoods, and their soils tend to be well-drained, sandy loams or silt loams that are often acidic and nutrient poor. In wetter sites, these habitats are called pine savannah wetlands, wet flatwoods or wet savannahs, and they can feature impressive stands of pitcher plant flowers in the spring. Some pine savannah wetlands have an impermeable hardpan layer not far beneath the surface that keeps the water table high during the rainy season but prevents moisture from rising through it during the dry season. This fluctuation between saturated and dry soils may play a key role, in combination with fire, in preventing the encroachment of trees and shrubs into the savannahs. Examples of these beautiful habitats are in Big Thicket NP and Gulf Islands National Seashore.

At San Antonio Missions NHP, there are small sections of woodlands dominated by huisache (Vachellia farnesiana) or mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) with occasional thornscrub elements, such as granejo (Celtis pallida) and pricklypear (Opuntia englemannii). Like some of the park's forested sections, these areas developed from old-field habitat and may represent a transitional stage.

Shrublands

Jane Carlson/NPS

Photo by Jane Carlson/NPS

Upland ecosystems that are dominated by shrubs are called shrublands, scrublands or simply scrub. In these habitats, shrubs form a thick to sparse layer no taller than 5 meters (16.4 feet [ft]) in height, and there are few to no overstory trees. At Palo Alto National Historical Park, there is Tamaulipan thornscrub on the park's lomas, which are higher elevation ridges left by historic river meanders. The thornscrub habitat consists of a rich assemblage of extremely thorny shrubs interspersed with prickly pear cactus and tree yuccas. These areas are particularly important habitat for the park’s resident population of Texas tortoises. The Rancho de las Cabras section of San Antonio Missions NHP also has similar thornscrub habitat with diverse species including Texas persimmon (Diospyros texana), lotebush (Ziziphus obtusifolia), brasil (Condalia hookerii), blackbrush (Vachellia rigidula) and Texas kidneywood (Eysenhardtia texana).

Upland shrubland habitats can also be seen at Gulf Islands NS, either as drought-tolerant, dwarf shrublands on relict dunes or thick oak scrub on more inland sections. The dwarf shrubands feature several salt tolerant shrubs or stunted trees, such as sand live oak (Quercus geminata), yaupon (Ilex vomitoria), sand heath (Ceratiola ericoides), false rosemary (Conradina canescens) and saw palmetto (Serenoa repens). The plant communities of the oak scrub, in contrast, can include a few taller trees such as sand pine (Pinus clausa) with a dense shrubby layer of several oak species (sand live oak, myrtle oak [Quercus myrtifolia], and Champan oak [Quercus champanii]), saw palmetto, sand heath, false rosemary, and cat-briar (Smilax spp.), among others. This habitat may also include open patches of sand colonized by ground lichens (Cladonia spp.).

Photo by C. Adams

Grasslands

Several Gulf Coast Network parks have unique dry grassland habitats. The Natchez Trace Parkway has small patches of blackland prairie at and around its Chickasaw Village site. Padre Island National Seashore is dominated by grasslands, with high abundance of Seacoast bluestem (Schizachyrium littorale) and gulfdune paspalum (Paspalum monostachyum). The sacahuiste grassland (Spartina spartinae) at Palo Alto NHP is very low elevation and on saline soil, but floods only occasionally. San Antonio Missions NHP has several park sections where native grasslands are being actively restored. This and other native grassland habitats in the region are seriously threatened by displacement from a variety of non-native grasses and encroachment from shrubs.

Back to top of page

Photo by GULN/NPS

Photo by C. Adams

Wetlands, Forested and Unforested

The Gulf Coast includes vast landscapes dominated by wetlands, most notably the densely forested lower Mississippi floodplain and its terminus, the deltaic plain. When a wetland has abundant trees, it is called a swamp (subjected to prolonged flooding) or a bottomland/floodplain forest (occasional flooding). At a smaller scale, a wetland may be dominated by shrubs, making it a scrub-shrub swamp. The third major type of freshwater wetland in the Gulf Coast Region is the marsh, which is characterized by a dense herbaceous layer and the general absence of trees. All Gulf Coast Network parks have some freshwater wetland habitats, with a few being particularly wetland-rich.

Photo by Jane Carlson/NPS

Photo by GULN/NPS

Freshwater Aquatic Ecosystems

All Gulf Coast Network parks have some fresh waterbodies, ranging from ponds, small streams, deep rivers and muddy bayous. Big Thicket NP was designed around the Neches river and its tributaries, and as such, these ecosystems are central to the park experience. Similarly, the river and its acequia system at San Antonio Missions NHP are defining for the park layout and also provide important aquatic habitat. Jean Lafitte NHP&P has many bayous and canals, including Bayou des Famillies in the Big Woods Unit. These waterbodies are essential to the life of each park and to the culture of the Gulf Coast region, where high value is placed on boating, paddling and where permitted, hunting and fishing. While providing key wildlife habitat, fresh waterbodies also create great opportunities for viewing diverse wading birds, raptors, alligators, turtles, fish, beavers and otters.

Back to top of page

Photo by C. Adams

Coastal and Near-Shore-Marine Ecosystems

Jane Carlson/NPS

Jane Carlson/NPS

The Gulf Coast region is frequently hit by hurricanes, and both its barrier islands and coastal mainlands are at risk of significant land loss. During storm surges after hurricanes, water can travel inland for miles. Both the high winds during the storm and the flooding with potentially salty water afterwards can affect vegetation dynamics throughout many of the network parks.

Barrier Islands, Beaches and Dunes

Most, but not all, of the beaches and dunes in Gulf Coast Network parks are found on its barrier islands. Gulf Islands NS has several barrier islands in its Mississippi section, including Horn, Petit Bois and Ship Islands. In the Florida section, there is Perdido Key and Santa Rosa Island. In a cross section from gulfward to inland, barrier islands begin with primary and secondary dunes, which are habitat for sea oats (Uniola paniculata), bitter panic grass (Panicum amarum), and Gulf Bluestem (Schizachyrium maritimum), with protected inland portions colonized by gulf croton (Croton punctatus), seabeach evening-primrose (Oenothera humifusa) and dixie sandmat (Chamaesyce bombensis), among others. Behind the dunes there may be pine trees and scrublands, with occasional mid-island freshwater wetlands. Finally, there is narrow beach, tidal marsh or tidal flats facing inland. Most island portions of Gulf Islands NS follow this profile. The Naval Live Oaks area is on mainland Florida, and it also has narrow beaches on its border with Pensacola Bay to the north and Santa Rosa Sound to the south. Davis Bayou in Mississippi is the only unit of Gulf Islands NS that lacks beaches and dunes; instead, its shoreline is dominated by salt marsh, which is akin to most of the coastline of neighboring Louisiana.

Jane Carlson/NPS

Padre Island NS is the largest undeveloped barrier island in the world at 70 miles (113 kilometers [km]) in length, and between it and the mainland is the hypersaline Laguna Madre. On both eastern and western sides of the island are expanses of sand, although the vegetated primary and secondary dunes are only on the gulfward side. On the interior border facing the Laguna Madre, there are algal flats and mudflats.

The beaches and dunes of both national seashores provide essential habitat for many organisms. On the beaches and associated habitats of both parks sea turtles lay eggs, shorebirds nest, and migratory birds rest enroute to their breeding or wintering grounds.

Tidal Marshes and Flats

Long stretches of coastline in Mississippi, Louisiana and Texas have marshes that are influenced by saltwater to varying degrees. These coastal wetlands are called salt marshes in the vegetated areas furthest from shore, where water salinity averages around 16 parts per thousand (ppt). Moving towards land, the marsh becomes brackish, with average salinity values of 8 ppt. These tidally-influenced areas may be adjacent to relatively barren mudflats with salt-tolerant succulents such as sea purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum), turtleweed (Batis maritima) and glassworts (Salicornia spp.).

The dominant plant species of most salt marshes is smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora), whereas brackish marshes contain a broader range of grasses, sedges, rushes and forbs. Example species including marshay cordgrass (Spartina patens), needlegrass rush (Juncus roemerianus), saltgrass (Distichlis spicata), perennial saltmarsh aster (Symphotrichum tenuifolium) and bushy seaside tansy (Borrichia frutescens). Salt and brackish marshes throughout the Gulf Coast play a key role in coastline stabiliziation, and they provide habitat for many birds and aquatic marine organisms, including juvenile fish that are important commerically.

Within the Gulf Coast Network, salt or brackish marshes are most abundant in the Davis Bayou Unit of Gulf Islands NS and portions Jean Lafitte NHP&P. At Padre Island NS, there are some salt marsh elements, although monodominant stands of Spartina alterniflora are absent. Instead, the most saline environments on the island are algal flats (sand encrusted with the algae Lyngbya confervoides) or sparsly vegetated mudflats, followed by brackish marsh plant communities.

Back to top of page

Photo by Chris Adams

Seagrass Meadows

In the near-shore-marine portions of Gulf Islands NS and Padre Island NS, there are large seagrass meadows. These meadows are in relatively shallow water with high light and nutrients. Seagrasses include several species of flowering plants that carpet the seabed, serving as food and nursery habitat for many marine organisms including commercially important fish species. Seagrasses also stabilize sediment and exhibit high primary productivity, acting as carbon sinks. Seagrass species of Gulf Coast Network parks include shoalgrass (Halodule wrightii), manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), star grass (Halophia engelmanii), turtlegrass (Thalassia testudinum), and widgeon grass (Ruppia maritima).

Photo by Joe Meiman/NPS

Anthropogenic Change in Gulf Coast Ecosystems

Photo by GULN/NPS

The Gulf Coast region continues to be affected by development, which exerts ever-increasing pressures, causing significant changes to regional and park ecosystems. Development includes population growth and associated land-use changes; engineering interference with natural water flows and coastal processes; habitat fragmentation; and water and air pollution. The population of the five Gulf Coast states increased greatly over the past several decades, with the most significant population increases occurring in Florida and Texas. Population growth in coastal areas of the nation has been more rapid than elsewhere, with more than half the U.S. population now living within 80 miles of coastal land. Population growth significantly affects the distribution of surface and ground water, both of which are critical for Gulf Coast ecosystems.

Major physical features of the Gulf Coast have been engineered over the past century to meet demands imposed by the ever-growing population. Alterations to water flows through dams and impoundments, channelization, dredge and spoil operations, and diking all affect the quantity and quality of discharge as well as the sediment input into coastal waters. This affects ecological functions such as estuarine productivity that depend on freshwater discharge from rivers, wetlands in the alluvial basins, and sand supplies from barrier islands. Irrigation for agriculture is becoming increasingly important throughout the Gulf Coast to buffer effects of extreme droughts. Four of the five states in this region are ranked among the nation's top 20 states in terms of irrigated land. Other significant draws on fresh water include thermoelectric power production, industrial uses, and household uses. Removing fresh water for human uses from river and coastal habitats typically results in degradation of these aquatic ecosystems.

Human economic, land, and resource development activities in the region have also greatly reduced or fragmented natural habitats. For example, increased coastline development has reduced wetland habitat. In the upland areas, agriculture and timber plantations have replaced natural prairies and forests.

Humans are also both directly and indirectly responsible for the movement and establishment of non-native invasive species that further degrade natural habitats and threaten native plants and animal species. Increasing human population, per-capita consumption, trade in the region, and human mobility have resulted in unprecedented levels of introduced, non-native species. When these introduced species become common, permanent residents, they can produce severe, often irreversible impacts on agriculture, recreation, and natural resources and threaten biodiversity, habitat quality, and ecosystem functioning.

In summary, while alterations of the landscape have enabled the human population of the Gulf region to grow and thrive, they have also caused widespread degradation of natural habitats, species invasions and displacement, and functional and structural shifts in ecosystems. Cumulatively, these human pressures on Gulf Coast water resources, ecosystems, biodiversity, and habitats are the most important drivers of ecosystem change in the region today.

Back to top of page

Last updated: February 12, 2025