|

Even before the mythology of the cowboy in the American "wild west" became popularized, Hawaiian cowboys (paniolo) were wrangling longhorn cattle on Hawaiʻi Island.

Introduction of Mammals to HawaiʻiAncient Hawaiʻi had no large land mammals. In fact, the only mammals endemic to Hawaiʻi were two species of bats (one extinct, the other is ʻōpeʻapeʻa— the Hawaiian hoary bat) and the ʻīlio-holo-i-ka-uaua (monk seal). When the Polynesian voyagers arrived, they brought an entire culture with them on their outrigger canoes including animals (chickens, pigs, dogs and, inadvertently, rats) and “canoe plants,” plants that were either food (taro, sweet potato) or otherwise useful (tī, kukui). Then came Western sailing ships and the introduction of more new plants and animals. In 1778 Captain James Cook brought both goats and pigs with him to Hawaiʻi to use as food and gifts.The Arrival of CattleCattle first arrived in the islands in 1793 when Captain James Vancouver presented King Kamehameha l with six cows and a bull. In order to encourage the herd’s growth, Kamehameha placed a kapu, a prohibition, on them so that they could not be hunted or killed. And grow they did, not merely flourishing but becoming a nuisance and even dangerous.. They rampaged through villages, literally eating the people out of house and home – they actually ate the thatch off the roofs of their houses, destroyed their crops, and sometimes hurt or even killed them.Ranching in HawaiʻiAround 1812, Kamehameha permitted the capture of wild cattle. Hawaiian ranching originally involved driving wild cattle into pits dug in the forest floor. Once tamed (somewhat) by hunger and thirst, they were hauled up a steep ramp, tied by their horns to the horns of a domesticated, older steer which was tractable and could be led to a fenced-in area.Slowly the beef industry began to grow under the reign of Kamehameha's son Liholiho (Kamehameha II). Liholiho's brother, Kauikeaouli (Kamehameha III), hearing about Mexican cowboys called vaqueros, invited a number of them to Hawaiʻi to teach his people how to work cattle. They taught the Hawaiians how to rope, slaughter, breed cattle, cure hides, about fences, grass, and paddocks. They also taught them how to work with the horses that had first arrived in the islands in 1803 when an American merchant ship brought four of them from California as gifts for Kamehameha I. Hawaiians quickly took to riding and roping, became skilled with the vaqueros’ tools and techniques, and then created a distinct and unique Hawaiian cowboy culture. They crafted their own style of saddles and gear and created their own style of music - songs accompanied by guitar and/or ʻukulele, stringed instruments whose portability was (and is) well-suited to cowboy life. They developed a singular Hawaiian style of open-tuning for the guitar called kihoʻalu, slack-key. These Hawaiian cowboys were called paniolo, a Hawaiianized version of the word español.

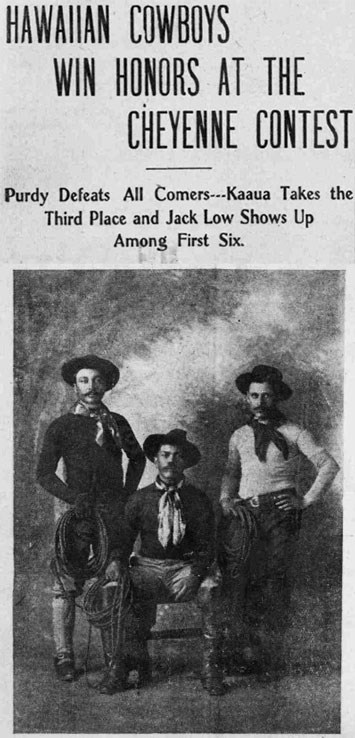

Famous PanioloIn 1908, three Hawaiians arrived in Cheyenne, Wyoming to compete in the biggest rodeo in the world, Frontier Days. Unlike the prototypical cowboys in the American west, Ikua Purdy and his cousins, Archie Kaʻauʻa and Jack Low, werenʻt white and they wore pāpale (hats) adorned with lei (garland). Their ʻohana, their families, had been riding and roping decades before the popularization of the American cowboy.What happened next overturned much of what people in the United States thought they knew about Hawaiʻi. In the World Championship finals, Ikua Purdy won the steer-roping contest in 56 seconds. Archie Kaʻauʻa came in second and Jack Low, despite suffering an asthma attack during the competition, placed sixth. Hawaii's paniolo had defeated the best American cowboys and had put Hawaiian paniolo on the world stage. Upon their return to Hawaiʻi, they were greeted as heroes with cheering crowds, parades, feasts, speeches, even poetry and hula composed in their honor. Their performance in Cheyenne came at an important moment in the history of a nation that was mourning its stolen sovereignty. As the Hawaiian Star newspaper put it: “[N]ow they have seen a man from the Parker Ranch beat all their champions, they will realize that the Hawaiian Islands are something more than a hula platform in the middle of the Pacific.”

Kahuku RanchThe Kahuku Ranch was a remote outpost and raising cattle there was a challenging business. About seventy five percent of the land was bare lava unsuitable for cattle. Other difficulties included clearing forested areas and planting pastures with imported grasses, and the not-uncommon volcanic eruptions and lava flows. Several large eruptions have occurred in Kahuku since the ranch was founded, notably 1868, 1887, and 1907. More impediments included a lack of surface water so that catchment and water transport systems had to be created and the fact that when the cattle were ready to be sold, markets were far away. Before refrigeration, cattle were shipped live and transferred from Kahuku to the Honolulu stockyards for sale.The sight of a paniolo riding their horses through the surf, swimming the cattle out to the longboats and tying the cattle by their heads to the sides of the boats to bring to steamers was a sight to behold. The paniolo then, in a truly death-defying feat, entered the water, fastened a strap under the cow’s belly by which it was hoisted onto the steamer. The cacaphony of cows bellowing, horses whinnying and paniolo shouting was unforgettable to anyone who witnessed it! Yet despite all the difficulties (and through 12 owners of varying competencies) the Kahuku Ranch kept going with talented paniolo for about 150 years, until it became a unit of Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park in 2003. Many people in Kaʻū trace their ancestry to the paniolo who worked in the area.

|

Last updated: June 24, 2024