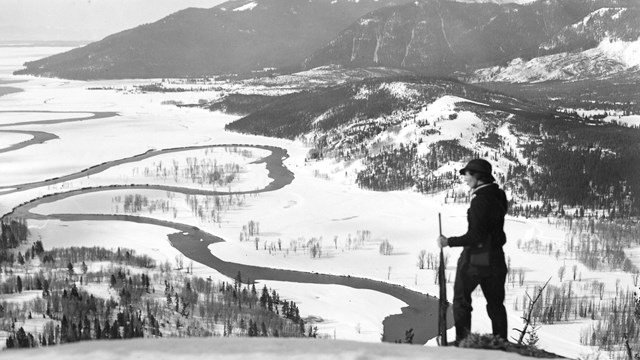

NPS Photo / CJ Adams Warmer temperatures and lower levels of precipitation both contribute to drying out vegetation (which fire managers call fuels). The drier the fuels, the more readily a fire will burn and spread. Fires spread most rapidly on days with warm temperatures, strong winds, and very low humidity levels—often called red flag days. With overall warmer temperatures and drier fuels, we will see more cases of extreme fire behavior. Climate change will also affect how forests regenerate after they burn. For example, some trees, like aspen, can quickly re-sprout from their roots after the rest of the plant burns in a fire. Ceanothus seeds actually wait in the soil for up to 150 years for a fire to “scarify”, or open, their seeds. Both of these plants have a strong advantage in regeneration after a fire. However, it may be more difficult for plants and trees that must germinate from seed after a fire, such as lodgepole pines. Many of these species are adapted to a relatively cool and wet climate, which this region has had for the past several thousand years. But as temperatures warm, some areas, like hot, south-facing slopes, may just be too hot for these conifer seedlings. Instead, those places would see more shrubby plants and wildflowers.

NPS Photo Learn more about how scientists are expecting climate change to affect fires and forests in Grand Teton in the Fire History Audio Tour.

Fire History

Explore the history of past fires in Grand Teton.

Fire Ecology

Find out more about fire's role in Greater Yellowstone.

Repeat Photos

Explore historic photos and recent retakes, which show how fire's effects on the landscape. |

Last updated: October 23, 2019