It all started in the Park Archives and Records Center at the Golden Gate National Recreation Area with a collection called “FOP: Presidio Judge Advocate’s Office Papers Collection, GOGA 39174.”The first story is this undated manuscript written by Presidio Army Museum Curator J. Phillip Langellier.

Time Capsules by J. Phillip LangellierHow often have you heard the old cliché, “If only that building could talk, what stories would it tell!” Here on the Presidio, a post with nearly two-hundred years of history, our buildings are talking. That’s right, every time reconstruction is done on Post, workers seem to find the walls telling their tales.

For instance, last Thursday a remodeling crew at the Post Judge Advocate’s offices went about their work. In the process, a carpenter lost his hammer. CW2 William L. Butts decided the tool couldn’t have just disappeared, so he began searching in the wall spaces near the workman’s area. Sure Enough, he came up with the hammer, and an unexpected surprise: Some old papers. His curiosity aroused, Butts made a methodical search of all the nooks and crannies where such material might hide.

Hours later, covered with decades of dirt, Butts emerged with numerous old bottles, tin cans, a World War I G.I. shaving kit, assorted insignia, socks, and a 1923 court-martial transcript for a private in the old 30th Infantry (“San Francisco’s Own”). Unfortunately, the unlucky soldier’s fate (he was caught sleeping on guard duty) is not yet known since the actual sentence is missing.

The walls also had writing on them indicating the location of storage bins for ham, sausage and other foodstuffs dating back to the days when this building served as a commissary’s storehouse for the nearby Post Stockage. Evidently, it also a convenient area for a soldier to slip away for a smoke or quick “pick-me-up.” Old cigarette packages, including Lucky Strike Greens, Coke Bottle, pints of “Ten High,” and in desperation, a few ounces of vanilla extract are evidence of this practice. Several cans of oysters are other clues to the past since soldiers at one time ascribed many powers to the denizens of the deep. This included the ability to sooth a raging hangover, or the mystical qualities now associated with vitamin “E.”

Major William Eckhardt, Staff Judge Advocate, thought these items might be of interest to the Museum. His phone call came as no surprise, however, since the museum itself has found its own share of artifacts secreted away in its attic. These included parts of uniforms dating back as early as the Civil War, hundreds of letters, many items associated with medical uses (the museum was the Old Station Hospital opened in 1857), and of course the usual supply of bottles, including a nice Olympia Beer container from the pre 1906 Earthquake days when Oly still had a bottling plant here.

Major Eckhardt’s quick thinking is what counted. While most of the items found have little monetary value, they are interesting links to the past which should be preserved. Any time someone cleans out an old attic or does construction work they may find themselves a sort of archaeologist. Hopefully, everyone will cooperate with the museum so that the items might be properly identified, preserved, and ultimately displayed for everyone enjoyment. In this respect, the wonderful time capsules will continue to provide an unusual link to the Presidio’s colorful past.

This article seems written for an audience who understood the Presidio army base, knew the location of the Judge Advocates office and was familiar with military practices and terminology. I wondered if it was published anywhere, but never found anything. It discusses office reconstruction and old buildings “talking,” including the museum structure in which Langellier was curator. He hints at the ability of these places to act each as impromptu archives, envisioning wall crevices as time capsules just waiting to be uncovered by an accidental historian.

The second story is an incomplete, 50-page transcript from a courts-martial hearing held at the Presidio of San Francisco in 1923. Although Langellier mentioned a lack of an ending, I hoped by reading it I would find some answers. On trial was 30th Infantry Private, Clarence A. McEachern, who was accused of sleeping while on sentry duty at the post guardhouse by Second Lieutenant Irvin Alexander during his rounds. Testimony contained in the surviving pages comes from Private Verry S. Hopper of the 8th U.S. Cavalry, and Second Lieutenant Robert E. Blair, First Lieutenant Thomas D. Conway, Corporal Otto Martin, and Captain Peter F. Salgado of the 30th U.S. Infantry. No locations, just more questions.

We have been given two points in time that create a view of the military legal system and like any good history they require us to ponder their greater implications. A possible first question could be, where was the Judge Advocates Office in the Presidio when Langellier wrote his article? Is it in the same place as it was in 1923? The second being where was the guardhouse that McEachern fell asleep and why was that offense serious? Finally, was a court-martial required?

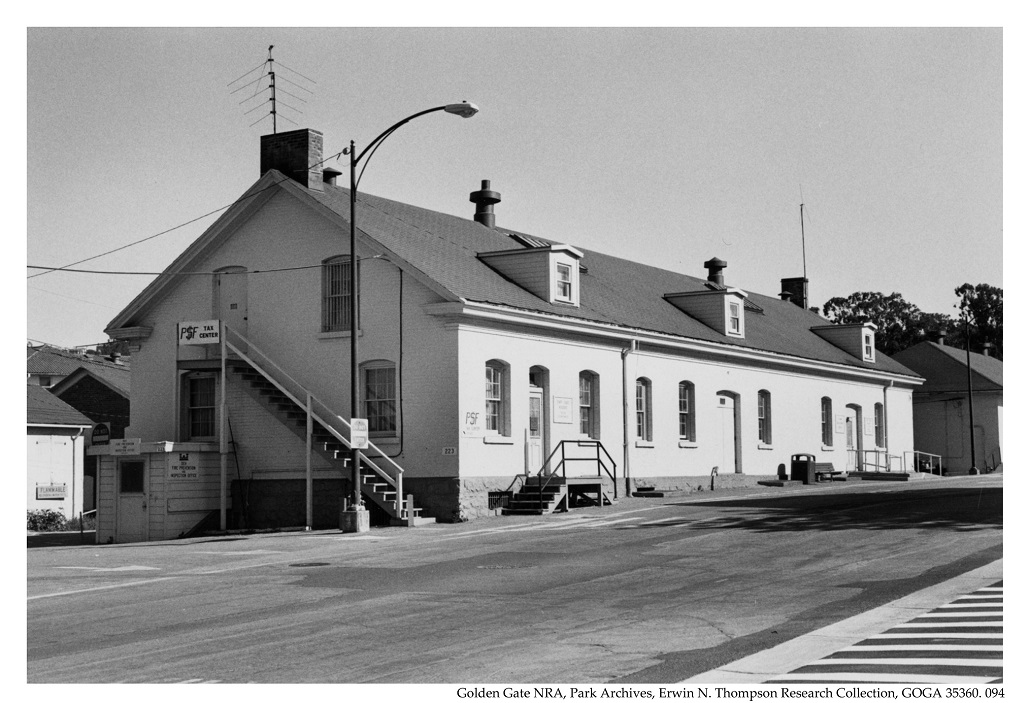

The first mystery of the Judge Advocate General’s location was a simple query in the GGNRA’s Army Text database for that name. The search revealed some folders in the Army Project Records Collection (GOGA 37252) which placed the office at 223 Halleck Street, closely situated to the museum. But as can be expected with archives this wasn’t a straightforward discovery.

The Army Projects Collection is massive, approximately 367 linear feet of material. With concern to Building 223 though, it contained a few files of as-builts and change orders from the 1980s detailing modifications required to make areas legally acceptable for private conversations with clients. There’s enough detail for us to infer that the work being described could be the same remodeling discussed in Langellier’s article and matches when he worked there as curator. However, the search led to more questions. If the “1923 Courts Martial” was found in the wall, does it mean the building has always been the Judge Advocates office? If so, how, and when was the structure used as place to “slip away to,” as described by the “Time Capsules” article? Perhaps soldiers were defiant in plain sight, or the building had convenient corners? Finally, why wasn’t there a room for private conversations prior to the 1980’s? Convinced, at least, this was the building mentioned by Langellier, but flush with other questions, I moved on to the second story with its questions- the trial.

The court transcript requires us to understand, in some small capacity, military court’s martial proceedings. Remember “the final sentence is missing” and subsequent searches for this case in hopes the ending had been digitized proved fruitless, the outcome remains “not yet known.” Being left with no new information, one can only wonder about conditions on the Presidio in 1923 that led to the extreme action taken. There was no war, danger, or known enemy, so why the heightened security and a court martial trial under the Articles of War? How did this paperwork end up in the wall? Was the document misplaced accidentally or on purpose? What became of the accused sleeping soldier? One thing’s for sure, if you ever wanted to read an argument about when a person should hear the jingling of hanging keys, or properly distinguish the sounds of different boot sole material, this is the court martial for you!

Both Langellier’s article and the 1923 court martial raise questions about military legal proceedings and the relationship with Presidio Building 223. They explore the army's interactions with history and how a soldier could create and save historic gems. The stories mysteries highlight the quest for knowledge that defines an archive, showing that, despite finding some information, satisfying conclusions are not always reached. Finally, the two documents exemplify how found stories can combine with existing records, potentially leading to new avenues of understanding (and frustration) … because these stories have no end.