NPS photo Everglades National Park was the first national park dedicated for its biologic diversity as opposed to its scenic vistas. Therefore, it is no surprise that when one thinks of scenic vistas in national parks, Everglades does not exactly spring to mind. Instead, spectacular visions of the painted deserts, sandstone canyons, mesas, and plateaus of the national parks in the southwestern United States may come to mind, such as the Grand Canyon. Easterners may think of the many strategically located scenic vistas in Shenandoah along Skyline Drive, which was specifically constructed so that motorists could enjoy the views as they toured the park. Some might imagine the granite monoliths and towering waterfalls of Yosemite, the glaciated mountains of Glacier National Park, or Denali's Mount McKinley, which is the tallest mountain peak in all of North America, rising to a summit elevation of 20,237 feet (6,168 meters) above sea level.

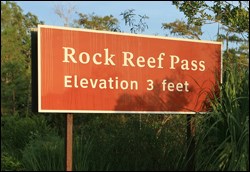

NPS photo Don't let that fool you! Although measured in inches instead of feet, an elevation change of even just a few inches in the Everglades leads to entirely different habitats, plant and animal communities – and landscapes. The astonishing and somewhat deceptive flatness of south Florida allows for immense landscapes that are easily viewed with only a slight boost in elevation. There is no need to exhaust yourself climbing mountains, or to drive on harrowing steep and narrow roadways, to enjoy the scenic vistas that the Everglades offer so generously to all. Shark Valley Observation Tower

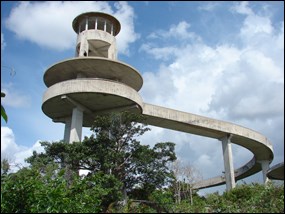

NPS photo Providing panoramic 360-degree views of the River of Grass, the Shark Valley Observation Tower is accessed from the midpoint of the 15-mile (24 km) Tram Road. This flat, paved road is used for tram rides, bicycling, and walking. Wildlife is commonly seen along the road. Below the Observation Tower is a short trail through a tropical hardwood hammock. Shark Valley is located in the northern part of the park and is accessed from the south side of the Tamiami Trail.

NPS photo The Shark Valley Observation Tower is a classic example of Mission 66 architecture, which is sometimes called "modern parkitecture" and features large slabs of concrete, swirling ramps, flat roofs, and terraces supported by thin columns. Implemented in 1956, Mission 66 was a 10-year program intended to dramatically improve and expand visitor services in national parks by 1966, in time for the 50th anniversary of the establishment of the National Park Service. Pa-Hay-Okee Overlook

NPS photo The short (0.16 miles or 260 meters, round trip) Pa-Hay-Okee Overlook boardwalk trail leads to sweeping vistas of the River of Grass. The parking area for this trail is located 13 miles (21 km) from the main park entrance/ Ernest Coe Visitor Center. The echolocation calls of a Seminole bat were recorded by a bat detector near Pa-Hay-Okee and can be heard by clicking on the audio file below. Visit the main bat webpage for an explanation of echolocation. The requested video is no longer available.

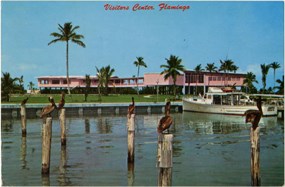

Flamingo

NPS photo by Tim Taylor Located at the end of the main park road about 38 miles south of the main park entrance, Flamingo amenities include a visitor center, campground, marina store, and public boat ramp. The seasonal Buttonwood Café operates from January to May. Other than the campground, lodging is not available at Flamingo because of damage sustained by Hurricanes Katrina and Wilma in 2005.

NPS photo by Tim Taylor In addition to spectacular views of Florida Bay, the covered breezeway on the second level of the Flamingo Visitor Center offers benches, protection from sun and rain, and even viewfinders. The breezeway is an comfortable place to relax and enjoy birding on the distant mudflats of Florida Bay, viewing sunrise and sunset, watching boats out on the bay, or even just daydreaming as you watch the clouds drift by. Assorted Flamingo trails for hiking, biking, and paddling are available in the area for visitors who would like to immerse themselves within the surrounding scenery.

Photo courtesy University of Florida Like the Shark Valley Observation Tower discussed above, the facilities at Flamingo are classic examples of Mission 66 "parkitecture." The buildings and structures collectively referred to as Flamingo Marina were designed by Cecil John Doty (1907-1990), one of the most prolific designers in National Park Service history. In addition to the visitor center, the Flamingo design included a lodge, restaurant, gas station, and an elaborate dock into Florida Bay with facilities for cruise boats.

Photo by Jack E. Boucher The modern Mission 66 building style featured concrete block, flat roofs, swirling concrete ramps, and terraces supported by thin columns. Louvered windows and perforated concrete screens provided ornamentation. Visitor centers constructed under the Mission 66 program were intended to be viewing platforms from which the park could be seen, while the buildings themselves were as transparent as possible.

NPS photo by Rodney Cammauf To achieve this goal, the original design features of the Flamingo Visitor Center include the upper-level breezeway that provides idyllic views of Florida Bay, a recessed ground floor that historically was used for – and hid – administrative offices, a ramped entrance and horizontal windows that emphasized the building's long and low lines, and the elevation of the information area and restaurant on the second floor. Currently, the seasonal Buttonwood Café is located on the ground floor where the administrative offices historically were located. Plans to rebuild the hurricane-destroyed Flamingo Lodge have been shelved because of budget constraints. Dark Night Skies

NPS photo by Tim Taylor Many visitors come to parks as some of the few remaining places to experience a dark night sky. Natural darkness is critical for nighttime scenery, such as viewing a starry sky, but also for maintaining nocturnal habitat.

Photo courtesy of Kristen Hart, USGS Many wildlife species rely on natural patterns of light and dark for navigation, to cue behaviors, or hide from predators. While lightscapes can be integral to the historical context of a place, human-caused light may be considered obtrusive for various reasons. Light that is undesirable in a natural or cultural landscape is often called light pollution. Light pollution can disrupt entire ecosystems, particularly for light-sensitive species such as sea turtles.

Image courtesy of NASA Poor air quality in combination with light pollution can lead to reduced ability to see starry skies. Air pollution can dim the stars and other celestial objects slightly, but more significantly, poor air quality scatters artificial light to a greater degree than clean air. This results in parks near cities and other significant light sources having greater sky glow than would be perceived in the absence of air pollution. Keeping Scenic Vistas Scenic

NPS Photo Many visitors come to national parks, including Everglades National Park, to enjoy the spectacular vistas. The ability to see landscape features, color, and detail in distant views is affected by air quality, as well as by development on public and private lands outside park boundaries. Poor visibility resulting from air pollution detracts greatly from visitor enjoyment of scenic vistas. As Class I Air Quality Areas, national parks such as Everglades are afforded the highest level of air-quality protection under the Clean Air Act. The National Park Service was created by the Organic Act in 1916 to conserve the resources and values of parks, including scenery, unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations. Under the Organic Act and the Clean Air Act, the National Park Service has a responsibility, and is required by law, to protect air quality and resources affected by air pollution.

NPS photo Understanding where air pollution comes from, what it is made of, and how it affects parks and park resources is essential for protecting national parks for future generations. The National Park Service Air Resources Division works in partnership with parks and other stakeholders to protect air quality and scenic views in parks. The division engages in outreach and communication as well as regulatory, planning, and other policy arenas to influence decisions and protect park resources. The Air Resources Division also conducts and facilitates scientific research, improving understanding about how air pollution impacts parks. |

Last updated: March 6, 2025