NPS / Jonathan Malriat The prairie dog is one of the most visible and appreciated animals seen at Devils Tower National Monument. It is also one of the most controversial. Whether you love them or loathe them, they are a critical member of the prairie ecosystem and an important resident at the national monument. The history, habits, and current status of prairie dogs is a fascinating case study in ecology, which includes how humans view and interact with our landscapes. The prairie dogs at Devils Tower represent how people manage a natural resource that has no direct benefit for human society. Description and HabitatThere are five different species of prairie dogs, all native to North America. Devils Tower is home to the most common, the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus). The prairie dog is a rodent of the squirrel family. They are tan or light brown in color, average 16 inches (40 cm) long, and weigh 1.5-3 pounds (average 1 kg). They have a 3-4 inch tail which is tipped in black (hence the name). Prairie dogs have small ears set close to their head and stout legs with long claws, adaptations for their burrowing lifestyle.

NPS / Avery Locklear The name "prairie dog" is derived from both their habitat and their habits. They live in the short grass prairie, and early European explorers likened them to small dogs because of their shrill, bark-like vocalizations. These calls are part of a complex communication system prairie dogs use for security. They are highly social animals that live in large groups known as "towns." These towns can cover dozens, if not hundreds, of acres. The largest reported town was from the 1800s in Texas, covering 25,000 square miles and hosting hundreds of millions of prairie dogs. That is an extreme example, as most towns are well under one square mile (640 acres). The town at Devils Tower is quite small, measured at around 42 acres in 2016.

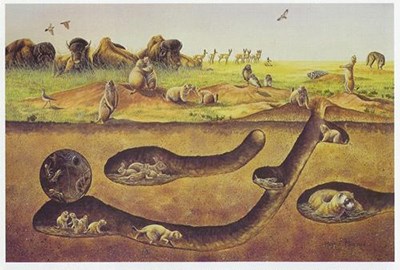

©Mark Marcuson and University of Nebraska-Omaha Habits and LifestylePrairie dogs are burrowing animals. They create their shelter by excavating tunnel systems which can be complex. Black-tailed prairie dogs also construct large mounds at some burrow entrances. A burrow is home to a single family unit and will be adjacent to family relatives' burrows. Groups of burrows are called coteries; a coterie (pronounced ko-der-ee) is defined as a close-knit group with similar interests. A coterie is run by a mature male, several females (a "harem" of 3-4 individuals), and their young. While a single burrow generally has multiple entrances, burrows are not all connected. Think of a prairie dog town like a human town: our towns have separated neighborhoods (coteries), and each neighborhood has separate houses (burrows). Most houses have more than one way in or out.

NPS / Leah Wilson Primarily herbivorous, these ground squirrels prefer grasses over forbs (flowering plants). They are opportunistic and will change their diets based on food availability and time of year. Prairie dogs also clip vegetation, including plants they do not consume. This gives their town a mowed appearance. Most plants in a prairie dog town do not grow higher than a few inches. This behavior is a part of their defensive strategy: it gives predators fewer places to hide, and allows prairie dogs to scan for danger across the entire town. Their habits of burrowing, grazing, and clipping are what make the prairie dog such an important member of their ecosystem; those behaviors also make them a maligned and controversial animal.

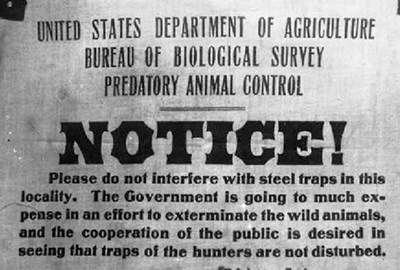

Keystone Species or Pest?As European Americans colonized the Great Plains, they saw a vast region to raise crops and livestock. However, there were a few native residents preventing the spread of agriculture. The subjugation of indigenous peoples and the elimination of bison and wolves removed most of the barriers to development. Prairie dogs were a lesser-known, but possibly more widespread, resident that ran contrary to the designs of the new colonizers. Imagine trying to raise crops on a homestead in Nebraska, only to find your freshly-tilled fields filled with these pesky rodents. What would you think if the Wyoming rangeland your cattle grazed became home to tiny creatures that seemed to remove the very grasses your livestock needed? The battle against the prairie dog began swiftly, and proved highly efficient. Estimates of prairie dog populations in the mid-1800s are in the billions. Within a century, they numbered a few million.The issue is larger than the story of any one species. It was not simply the populations of a few select animals, but rather the status of an entire ecosystem. The Great Plains was converted to a breadbasket, designed not to support biodiversity but to feed and house a growing population of a single organism: human beings. It is a familiar story with a familiar shift; by the late 1900s, efforts were underway to preserve the last remnants of North America's prairies. And you cannot have a prairie without the prairie dog. A comprehensive study in 2004 determined that black-tailed prairie dogs occupied close to 2 million acres of land (7,500 km2). This is up from a low of around 400,000 acres (1,500 km2) in 1961. Large portions of their present-day territory are on protected lands like our national parks. This provides an opportunity to study the prairie dog in a natural setting and determine its role in the ecosystem. There are also many studies on the relationship between these animals and the domestic livestock they sometimes share habitat with.

NPS photo Keystone SpeciesA keystone species is an organism that provides important habitat benefits for other members of its ecosystem. Biologists consider prairie dogs to be in this category, partly because of their importance as a prey species to most predators. Prairie dogs burrows are utilized by many creatures—other small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, burrowing owls, etc.—as well. Their burrowing activities mix and aerate soil. Their grazing and clipping habits suppress vegetation growth, which in some plants increases their nutritional qualities. In all, biodiversity is higher in grasslands with prairie dogs than in those without. Studies show that many grazers, including bison, pronghorn, and domestic cattle, prefer foraging in prairie dog towns.PestsRegardless of their ecological benefits, prairie dogs are still considered pest animals by many. Most states with prairie dog populations list them as varmints or noxious, and landowners are free to eliminate prairie dogs as they see fit. Although declaring these native animals as destructive pests is ironic, there is logic behind the mentality. Consider our above examples of farming and ranching in areas with prairie dogs. It can be hard to manage your land with creatures digging holes all over it and consuming the resources you depend upon for your livelihood. For many, it is a simpler idea to remove the creature than balance your land management for multiple uses.

NPS / Leah Wilson Prairie Dogs at Devils TowerThe prairie dogs at the monument live in a small community that has mild population changes. The town is around 40 acres with 600 residents. Although some predators are present (foxes, badgers, and eagles are most common), not enough exist to fully keep the town's population in check; this may be because the town itself is not big enough to support enough natural predators (and like prairie dogs, many of their predators are unwelcome on neighboring private lands). Occasionally, disease plays an important role in population control. Prairie dogs are susceptible to sylvatic plague, tularemia, and other flea- or tick-borne diseases. In rare scenarios, the park will relocate or remove prairie dogs; this was the case around 2010 when their town began to spread into our picnic and campground areas. One of our most effective methods of controlling their spread into these areas was to simply stop mowing some locations; prairie dogs colonize areas that are heavily grazed, and by allowing the grasses to grow they were less inclined to move into that territory.We ask that you enjoy prairie dogs from a distance to keep them wild, and keep yourself and the animals safe. They can be easily seen from the park road, and there are several paved pullouts constructed for that very purpose. It is illegal to feed any animal in a national park.

NPS photo Although the debate may swirl in communities near the Tower and other park sites with prairie dogs, the park lands provide a sanctuary for the chunky ground squirrels. They find a home on these protected lands, which may help keep them out of areas where they are unwanted. The prairie dogs at the nation's first national monument are descended from animals who lived here long before cattle ever grazed in the valley of the Belle Fourche River. Today, they entertain people from around the world; visitors come to see the Tower, but may take just as many (or more) pictures of our little furry residents. They represent an iconic animal of the Great Plains. They are active throughout the day, easily visible from the park road. Their antics delight the casual observer and the dedicated nature photographer. Are our prairie dogs aware of the controversies which surround them? Do they know of their complex history with human society, sharing stories of the first prairie dogs captured by Lewis and Clark (it took them four days!)? Probably not. They are just happy to munch some grass and avoid the badgers. More About Prairie DogsThere are many places to discover more about these creatures. This page focused generally on their behaviors and their relationship with humans. You can find more specific information about these topics, or delve deeper into the natural history of prairie dogs. Below are a few places to look.

Prairie Dogs Across the Park Service |

Last updated: April 24, 2025