|

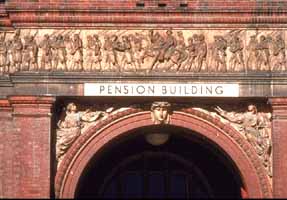

1880s brick building with terra-cotta trim. |

The

longevity and appearance of a masonry wall is dependent upon the

size of the individual units and the mortar.

Stone

is one of the more lasting of masonry building materials and has

been used throughout the history of American building construction.

The kinds of stone most commonly encountered on historic buildings

in the U.S. include various types of sandstone, limestone, marble,

granite, slate and fieldstone. Brick varied considerably

in size and quality. Before 1870, brick clays were pressed into

molds and were often unevenly fired. The quality of brick depended

on the type of clay available and the brick-making techniques; by

the 1870s--with the perfection of an extrusion process--bricks became

more uniform and durable. Terra cotta is also a kiln-dried

clay product popular from the late 19th century until the 1930s.

The development of the steel-frame office buildings in the early

20th century contributed to the widespread use of architectural

terra cotta. Adobe, which consists of sun-dried earthen bricks,

was one of the earliest permanent building materials used in the

U.S., primarily in the Southwest where it is still popular.Mortar is used to bond together masonry units. Historic mortar was generally quite soft, consisting primarily of lime and sand with other additives. After 1880, portland cement was usually added resulting in a more rigid and non-absorbing mortar. Like historic mortar, early stucco coatings were also heavily lime-based, increasing in hardness with the addition of portland cement in the late 19th century. Concrete has a long history, being variously made of tabby, volcanic ash and, later, of natural hydraulic cements, before the introduction of portland cement in the 1870s. Since then, concrete has also been used in its precast form.

While masonry is among the most durable of historic building materials, it is also very susceptible to damage by improper maintenance or repair techniques and harsh or abrasive cleaning methods.

|

|

Masonry

|

....Identify,

retain, and preserve

|

|

|

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Materials and craftsmanship illustrated in stone wall. |

Identifying,

retaining, and preserving masonry features that are important in

defining the overall historic character of the building such as

walls, brackets, railings, cornices, window architraves, door pediments,

steps, and columns; and details such as tooling and bonding patterns,

coatings, and color.

|

|

not

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Removing

or radically changing masonry features which are important in defining

the overall historic character of the building so that, as a result,

the character is diminished.

Replacing

or rebuilding a major portion of exterior masonry walls that could

be repaired so that, as a result, the building is no longer historic

and is essentially new construction.

Applying

paint or other coatings such as stucco to masonry that has been

historically unpainted or uncoated to create a new appearance.

Removing

paint from historically painted masonry.

Radically

changing the type of paint or coating or its color.

|

|

Masonry

|

....Protect

and Maintain

|

|

|

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Chemical cleaning to remove dirt from granite. |

Protecting

and maintaining masonry by providing proper drainage so that water

does not stand on flat, horizontal surfaces or accumulate in curved

decorative features.

Cleaning

masonry only when necessary to halt deterioration or remove heavy

soiling.

Carrying

out masonry surface cleaning tests after it has been determined

that such cleaning is appropriate. Tests should be observed over

a sufficient period of time so that both the immediate and the long

range effects are known to enable selection of the gentlest method

possible.

Removing felt-tipped

marker graffiti with poultice. |

Cleaning

masonry surfaces with the gentlest method possible, such as low

pressure water and detergents, using natural bristle brushes.

Inspecting

painted masonry surfaces to determine whether repainting is necessary.

Removing

damaged or deteriorated paint only to the next sound layer using

the gentlest method possible (e.g., handscraping) prior to repainting.

Applying

compatible paint coating systems following proper surface preparation.

Repainting

with colors that are historically appropriate to the building and

district.

Evaluating

the overall condition of the masonry to determine whether more than

protection and maintenance are required, that is, if repairs to

the masonry features will be necessary.

|

|

not

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Failing

to evaluate and treat the various causes of mortar joint deterioration

such as leaking roofs or gutters, differential settlement of the

building, capillary action, or extreme weather exposure.

Cleaning

masonry surfaces when they are not heavily soiled to create a new

appearance, thus needlessly introducing chemicals or moisture into

historic materials.

Cleaning

masonry surfaces without testing or without sufficient time for

the testing results to be of value.

Historic brick damaged by sandblasting. |

Sandblasting

brick or stone surfaces using dry or wet grit or other abrasives.

These methods of cleaning permanently erode the surface of the material

and accelerate deterioration.

Using

a cleaning method that involves water or liquid chemical solutions

when there is any possibility of freezing temperatures.

Cleaning

with chemical products that will damage masonry, such as using acid

on limestone or marble, or leaving chemicals on masonry surfaces.

Applying

high pressure water cleaning methods that will damage historic masonry

and the mortar joints.

Removing

paint that is firmly adhering to, and thus protecting, masonry surfaces.

Using

methods of removing paint which are destructive to masonry, such

as sandblasting, application of caustic solutions, or high pressure

waterblasting.

Failing

to follow manufacturers' product and application instructions when

repainting masonry.

Using

new paint colors that are inappropriate to the historic building

and district.

Failing

to undertake adequate measures to assure the protection of masonry

features.

|

|

Masonry

|

....Repair

|

|

|

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Repairing

masonry walls and other masonry features by repointing the mortar

joints where there is evidence of deterioration such as disintegrating

mortar, cracks in mortar joints, loose bricks, damp walls, or damaged

plasterwork.

Preparation for stucco repair. |

Removing

deteriorated mortar by carefully hand-raking the joints to avoid

damaging the masonry.

Duplicating

old mortar in strength, composition, color, and texture.

Duplicating

old mortar joints in width and in joint profile.

Repairing

stucco by removing the damaged material and patching with new stucco

that duplicates the old in strength, composition, color, and texture.

Using

mud plaster as a surface coating over unfired, unstabilized adobe

because the mud plaster will bond to the adobe.

Cutting

damaged concrete back to remove the source of deterioration (often

corrosion on metal reinforcement bars). The new patch must be applied

carefully so it will bond satisfactorily with, and match, the historic

concrete.

Replacement

stones tooled to match original. |

Repairing

masonry features by patching, piecing-in, or consolidating the masonry

using recognized preservation methods. Repair may also include the

limited replacement in kind--or with compatible substitute material--of

those extensively deteriorated or missing parts of masonry features

when there are surviving prototypes such as terra-cotta brackets

or stone balusters.

Applying

new or non-historic surface treatments such as water-repellent coatings

to masonry only after repointing and only if masonry repairs have

failed to arrest water penetration problems.

|

|

not

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Removing

nondeteriorated mortar from sound joints, then repointing the entire

building to achieve a uniform appearance.

Loss

of the historic character due to insensitive repointing. |

Using

electric saws and hammers rather than hand tools to remove deteriorated

mortar from joints prior to repointing.

Repointing

with mortar of high portland cement content (unless it is the content

of the historic mortar). This can often create a bond that is stronger

than the historic material and can cause damage as a result of the

differing coefficient of expansion and the differing porosity of

the material and the mortar.

Repointing

with a synthetic caulking compound.

Using

a "scrub" coating technique to repoint instead of traditional repointing

methods.

Changing

the width or joint profile when repointing.

Removing

sound stucco; or repairing with new stucco that is stronger than

the historic material or does not convey the same visual appearance.

Applying

cement stucco to unfired, unstabilized adobe. Because the cement

stucco will not bond properly, moisture can become entrapped between

materials, resulting in accelerated deterioration of the adobe.

Patching

concrete without removing the source of deterioration.

Replacing

an entire masonry feature such as a cornice or balustrade when repair

of the masonry and limited replacement of deteriorated of missing

parts are appropriate.

Using

a substitute material for the replacement part that does not convey

the visual appearance of the surviving parts of the masonry feature

or that is physically or chemically incompatible.

Applying

waterproof, water repellent, or non-historic coatings such as stucco

to masonry as a substitute for repointing and masonry repairs. Coatings

are frequently unnecessary, expensive, and may change the appearance

of historic masonry as well as accelerate its deterioration.

|

|

Masonry

|

....Replace

|

|

|

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Replacing

in kind an entire masonry feature that is too deteriorated to repair--if

the overall form and detailing are still evident--using the physical

evidence as a model to reproduce the feature. Examples can include

large sections of a wall, a cornice, balustrade, column, or stairway.

If using the same kind of material is not technically or economically feasible, then a compatible substitute material may be considered.

|

|

not

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Removing

a masonry feature that is unrepairable and not replacing it; or

replacing it with a new feature that does not convey the same visual

appearance.

|

| |

Design

for Missing Historic Features

The

following work is highlighted to indicate that it represents the

particularly complex technical or design aspects of rehabilitation

projects and should only be considered after the preservation concerns

listed above have been addressed.

|

|

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Designing

and installing a new masonry feature such as steps or a door pediment

when the historic feature is completely missing. It may be an accurate

restoration using historical, pictorial, and physical documentation;

or be a new design that is compatible with the size, scale, material,

and color of the historic building.

|

|

not

recommended.....

|

|

| |

Creating

a false historical appearance because the replaced masonry feature

is based on insufficient historical, pictorial, and physical documentation.

Introducing

a new masonry feature that is incompatible in size, scale, material

and color.

|

|