“MAN THE BEACH CART!” Throughout our nation’s history, the sea has played a significant role in American life. Despite this heritage, the federal government did not consider lifesaving worthy of its concern for many years. More consideration was given to the cargo lost in shipwrecks than to the human victims of such disasters. It was not until 1848 that federal funds were first committed to limited lifesaving efforts. Volunteers staffed scattered facilities for over two decades before a professional lifesaving service was finally created in 1871 as a unit of the U.S. Treasury’s Revenue Marine Bureau.

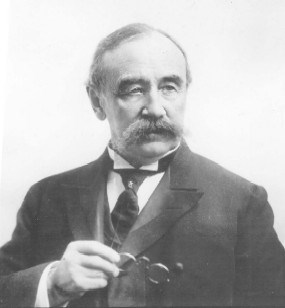

Smithsonian Institution The new U.S. Life-Saving Service suffered from a lean budget and widespread problems. Training and equipment were either poor or non-existent, and many of its “lifesavers” were either incompetent land-lubbers or corrupt political appointees. Sumner I. Kimball, head of the Revenue Marine Bureau, worked hard to cleanse the fledgling service of these ills. Two tragic shipwrecks along the North Carolina coast (U.S.S. Huron at Nags Head in November, 1877 and the Metropolis at Currituck Beach in January, 1878) called further public attention to the shortcomings of the agency. Finally in June 1878, the U.S. Life-Saving Service was made an independent unit of the Treasury Department with Kimball as its first superintendent. It went on to forge an extraordinary record of proficiency, dedication, and heroism before becoming a part of the new U.S. Coast Guard in 1915. Superintendent Kimball recognized that dependable personnel, proven equipment, and standardized rescue drills were all vital to the long-term success of the U.S. Life-Saving Service. He devoted a great deal of energy to each of these elements, for if any one of them was lacking, lives could be lost as a result. Outer Banks Life-Saving StationsThe first Outer Banks Life-Saving Service (LSS) stations were built and manned in 1874. They were, from north to south, Jones Hill (later with the more familiar name “Currituck Beach”), Caffeys Inlet, Kitty Hawk, Nags Head, Bodie island (renamed “Oregon Inlet”), Chicamacomico (now village of Rodanthe) and Little Kinnakeet (just north of today’s village of Avon). In 1878, eleven more stations were added. These included the now famous Kill Devil Hills station, which assisted the Wright brothers, and the Hatteras Inlet station. Still more were added, eventually totaling 29, averaging about six miles apart on the North Carolina outer coast from the Virginia line (Wash Woods LSS – 1878), to the South Carolina line (Oak Island LSS- 1886). In 1915, all these became Coast Guard stations. US Life-Saving Service in Cape Hatteras National SeashoreUnited States Life-Saving Service stations on Bodie, Hatteras and Ocracoke Islands – includes the area in 1953 which became the Cape Hatteras National Seashore – were Bodie Island, Oregon Inlet, Pea Island, New Inlet, Chicamacomico, Gull Shoal, Little Kinnakeet, Big Kinnakeet, Creeds Hill, Cape Hatteras, Durants, Hatteras Inlet and Ocracoke. Two highly significant United States Life-Saving Service complexes of those stations still exist that are properties of the National Park Service, Cape Hatteras National Seashore. They are Bodie Island Life-Saving Station and Little Kinnakeet Life-Saving Station.

NPS Lifesaving EquipmentGood equipment went hand-in-hand with training. Though several heroic rescues were accomplished with the use of little or no equipment, few lifesavers could do their jobs without it. Keeping the equipment clean and functional was as crucial as any training, and one day each week was devoted to this task. The surfboat, so-called because it was launched directly into the ocean surf, was the favored rescue equipment. It was rowed out close to the wreck and carried large numbers of people to safety at one time. Later surfboats were powered, though use of the oars was still required for launching and close maneuvers. Teamwork, training, and experience were essential for proper handling of the surfboat. A second type of rescue equipment was the beach apparatus or breeches buoy. This was used when the wreck occurred close to shore and sea conditions disallowed the use of the surfboat. Due to the frequency of severe storms with heavy seas and shipwrecks that occurred near or on the beach, breeches buoy rescues were fairly common on the Outer Banks.

All necessary equipment was hauled in a heavy cart called a beach cart to the scene of the wreck. This was a difficult and time-consuming task because, initially, few stations had draft animals and, therefore, the cart had to be pulled by the surfmen. In ordinary conditions, this would be a strenuous duty but in the soft, wet sand of a dark, storm-swept beach, it was utterly exhausting work that could take several hours. This problem was further complicated by the vast distances each station had to cover in the early years of the Service until additional stations were constructed. Breeches buoy rescues were practiced each week in a training exercise called the Beach Apparatus Drill. Development of teamwork, speed, and precision were crucial since, ideally, each rescue would follow the same pattern regardless of any adverse conditions. Each man had to know exactly what to do at the proper time or the entire rescue would become a disaster. Watching for WrecksOne of the most basic, yet altogether crucial duties in the U.S.L.S.S., was patrolling the beach, for no rescues could be attempted and no lives could be saved unless the shipwrecks themselves were found. There were two main ways to achieve this goal. The first was manning the watch tower. The surfmen rotated the duty of keeping watch at all times from this vantage point, scanning the surrounding area for ships. Though the height of the tower was meant to improve the viewing range, visibility was often greatly reduced in poor weather. The other method, beach patrols, were more reliable. Each surfman was assigned a period of time (usually 2-4 hours long) and a direction to walk (or ride a horse, if available) up the beach, keeping watch. They were required to go half-way between their station and the next (stations were generally seven miles apart), where they turned a time-clock with a special key or exchanged a “patrol check” with a surfman from the other station. The check was then shown to the Keeper as proof that they had completed their patrol. The vast majority of U.S.L.S.S. rescues on the Outer Banks began with a surfman on beach patrol, keeping an eye out for any sign of a vessel in trouble. Discovery of a shipwreck came in many forms: distress, flares, debris, corpses, shouts or cries, or the sound of flapping sails could all indicate a wreck. Once one was found, the surfman’s next job was to signal to the survivors that they had been spotted, using a red flare called a Coston Signal. This gave the survivors much needed hope and also alerted them of the forthcoming rescue attempt (ships sailing dangerously close to shore could also be signalled or “warned off” using a Coston Flare). The surfman would then immediately return to the station and inform the Keeper of the wreck. Some Famous Rescues on the Outer Banks

NPS Of the many surfboat rescues on the Outer Banks, two are particularly noteworthy. On December 22, 1884, Keeper Benjamin B. Dailey of Cape Hatteras Station and his crew took their surfboat into the huge breakers crashing ashore and through immense seas to the wreck of the Ephraim Williams. Overcoming the tremendous odds stacked against them, they returned safely with all nine of the vessel’s crewmen, a tremendous feat of skill and bravery. An investigator later stated:

Another famous surfboat rescue occurred during World War I, when enemy submarines operated in American coastal waters. On August 16, 1918, the British tanker Mirlo struck a German mine a few miles offshore and blew up. Keeper John Allen Midgett and his crew from Chicamacomico Station launched their surfboat and steered it into a fiery seascape of burning oil, seeking survivors. Maneuvering their way through a hellish environment that blistered paint on their boat, burned their skin, and singed their hair and clothing, the lifesavers emerged with 42 rescued crewmen. Both the United States and Great Britain awarded Keeper Midgett and his surfmen medals for their gallantry.

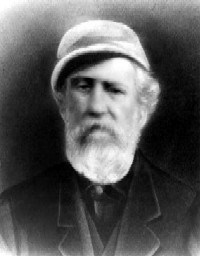

Outer Banks History Center, Collier Cobb photo Sometimes a surfman was forced to improvise a rescue, such as Surfman Rasmus S. Midgett of the Gull Shoal Lifesaving Station did during the “San Ciriaco” hurricane of August 1899. Several ships had been caught at sea by the deadly storm including the schooner Priscilla, which was driven ashore on the Outer Banks. Fighting his way through the shrieking wind and flooded sands of his patrol route, Midgett discovered the Priscilla as it began to go to pieces in the surf, three miles south of the station. With no time to return for help, he was forced to act on his own and without any equipment. Plunging into the furious Atlantic, he called for one of the desperate survivors to jump down. A man did so and Midgett assisted him back to the relative protection of the beach. He returned six more times to the wreck, each time bringing another crewman to safety. Three more times he went out, only now he had to climb up to the remnants of the ship and lift the exhausted men to his shoulders, carry them down into the water, and then drag them back to shore. All of this he did on his own, without aid or equipment, using only his strength, skill, and an immense amount of selfless bravery. For this, perhaps the greatest individual effort in the history of lifesaving, the government presented to Rasmus Midgett the Gold Lifesaving Medal of Honor.

NPS, David Stick Collection The Heritage Lives OnThough officially the U.S. Life-Saving Service era ended in 1915, the U.S. Coast Guard has continued its heroic tradition. Helicopters and nimble patrol vessels have long-since replaced surfmen on beach patrol and surfboats for lifesaving, but the goal – “to rescue lives from the perils of the sea” – remains intact. Cape Hatteras National Seashore preserves the history of the U.S. Life-Saving Service on the Outer Banks. Walk the same beaches that Rasmus Midgett once patrolled or stop and see what Keeper Dailey’s medal looks like at the Museum of the Sea near the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Look in awe at the crashing surf and realize that men once launched boats into such waves to help others. View one of the shipwreck remnants in the park and consider the rescue that might have accompanied it and remember the heroes.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

Join author and storyteller, James Charlet, as he discusses the historic 1884 Gold Medal rescue of the Ephriam Williams by Keeper Benjamin B. Dailey and the crew of the Cape Hatteras United States Lifesaving Service Station. |

Last updated: August 30, 2023