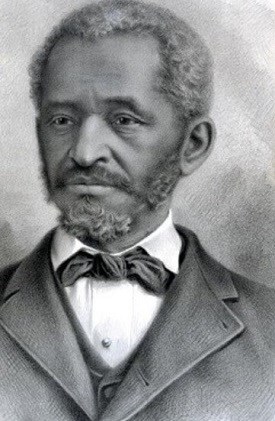

NPS Photo The Lewis and Harriet Hayden House at 66 Phillips (formerly Southac) Street served as the preeminent Underground Railroad safe house in Boston during the 1850s. In the 1840s, the Haydens escaped slavery in Kentucky and eventually settled in Boston. They lived in this house by 1850, operated it as a boardinghouse, and turned it into one of the most documented safe houses in the area. Following the passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, Bostonians created their third and final Vigilance Committee, an organization dedicated to fugitive assistance. As one of the most active members of this committee, Lewis and Harriet Hayden sheltered and assisted many freedom seekers. The Treasurer's Account Book of the Vigilance Committee documents many of Lewis Hayden's Underground Railroad activities. For example, an entry from November 1850 recorded Hayden "boarding Fugitives John Simmons, W. Miller, Ja. Jackson, Solomon Bander, Geo. Reason, Issac Mason & Wife."1 A September 16, 1852 entry records reimbursement to "Lewis Hayden for Taylor and Coopers fare to Canada also boarding W. Brown, Cooper, Mary Brown & children."2 In November 1855, he provided "clothes for Henry Demby and board of J. Holmes."3 Numerous entries throughout the account book, such as these, indicate that Hayden sheltered or otherwise assisted scores of freedom seekers throughout the Fugitive Slave Law years. He provided shelter, clothing, carriages and fare to get people out of the city and further North to freedom.

Cleveland Gazette, February 24, 1894 While Lewis's name appears throughout the Vigilance Committee records, historian Steven Kantrowitz reminds us to remember the essential contributions of Harriet. In his book More Than Freedom, Kantrowitz states: The numerous payments made by the Vigilance Committee to Lewis Hayden, for example, almost certainly do not reflect the division of labor within the Hayden household, which in the early 1850s included a boardinghouse and a used-clothing store. It may well have been Lewis Hayden himself who provided fugitives with clothing and hired carriages to take them out of the city. But while he moved about the city, who took charge of the residence up the hill on Southac Street, and its many boarders? Almost certainly the day-to-day management of the boardinghouse was Harriet Hayden’s responsibility…the couple’s labors were complementary and mutually necessary.4 A fellow Vigilance Committee member, Austin Bearse, recalled bringing Harriet Beecher Stowe to visit the Haydens and encountering many freedom seekers at their home: When, in 1853, Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe came to the Liberator Office, 21 Cornhill, to get facts for her "Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin," she was taken by Mr. R. F. Wallcutt and myself over to Lewis Hayden's house in Southac Street, where thirteen newly-escaped slaves of all colors and sizes were brought into one room for her to see. Though Mrs. Stowe had written her wonderful “Uncle Tom”… expressly to show up the workings of the Fugitive-Slave Law, yet she had never seen such a company of "fugitives" together before. Mr. Lewis Hayden was himself a remarkable fugitive slave, whose story Mrs. Stowe introduced in her "Key."5

Public Domain In 1850, the Haydens sheltered the famous couple William and Ellen Craft. The Crafts escaped from slavery in Georgia with an elaborate disguise and story. The light-skinned Ellen dressed in men's clothing and "passed" as a White male slaveholder traveling North by train and ship with her trusted "slave" William. The federal census taken in August 1850 lists the Crafts residing at the Hayden House. In October 1850, slave catchers came looking for the couple in Boston's first test of the new Fugitive Slave Law. According to William Craft, "Lewis Hayden and I had a keg of gunpowder under his house in Phillips Street, with a fuse attached ready to light it should any attempt be made to capture us."6 Given all of the abolitionist hostility and threats to their safety, the slave catchers abandoned their pursuit of the Crafts. A correspondent for The Liberator, Boston's major abolitionist newspaper, later wrote that the U.S. Marshal, acting as a slave catcher, called off his arrest of the Crafts because "He knew that the road to hell lay over Lewis Hayden’s threshold; and the cost to him would be rather more than the Slave Power would be ready to make up to him."7 In addition to protecting the Crafts, Lewis Hayden also played a crucial role in other high-profile Fugitive Slave Law cases in the city. On February 15, 1851, slave catchers arrested Shadrach Minkins, who had escaped from Virginia months earlier. Within three hours of Minkins' arrest, Hayden led a group of Black men in a daring courthouse rescue, freed Minkins from his captors, and successfully got him out of the city and further on the Underground Railroad network to Canada. In 1854, Hayden and others attempted to rescue Anthony Burns from federal custody at the same courthouse. Unfortunately, they failed, and authorities soon returned Burns to the South under heavy martial guard. A long-time colleague of Lewis Hayden, Henry Ingersoll Bowditch recalled that Haydens' house served as "the temple of refuge for any hunted refugee from Southern slavery."8 The Lewis & Harriet Hayden House is listed as a site on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. To learn more about the Network to Freedom, please visit their website. Footnotes:

|

Last updated: December 13, 2024