The mill village of Ashton, located in present-day Lincoln, Rhode Island, is one of the best examples of a well-preserved Rhode Island System mill village. The village also tells the stories of revolutions in manufacturing and transportation. The opening of the village of Slatersville in 1807 proved that mills could be built anywhere in the Blackstone Valley where there was enough water. If they found the right spot along a river, mill owners could build everything else they needed. In 1809, George Olney and six other partners founded the Smithfield Cotton and Woolen Company. This was an early example of replicating water-powered textile machines in the United States by someone outside the Slater family. Olney and his partners built their mill at Prays Wading, in modern day Lincoln, RI. Prays Wading is a naturally shallow spot along the Blackstone River that was used by Indigenous peoples for thousands of years as a river crossing. Each partner contributed land or money to the project. The company constructed the mill by 1815. This first mill was small, measuring 30 by 60 feet, with 252 spindles and 5 carding machines. Over the next five years, the operation continued to expand – by 1820, the company erected a gristmill and four small workers’ homes, the largest of which was reserved for the mill’s manager. The mill made textiles, which were in high demand due to the Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812. Both of these events banned imported cloth from Europe, allowing American manufacturers such as Olney and his partners to produce goods without having to compete with cheap European cloth.

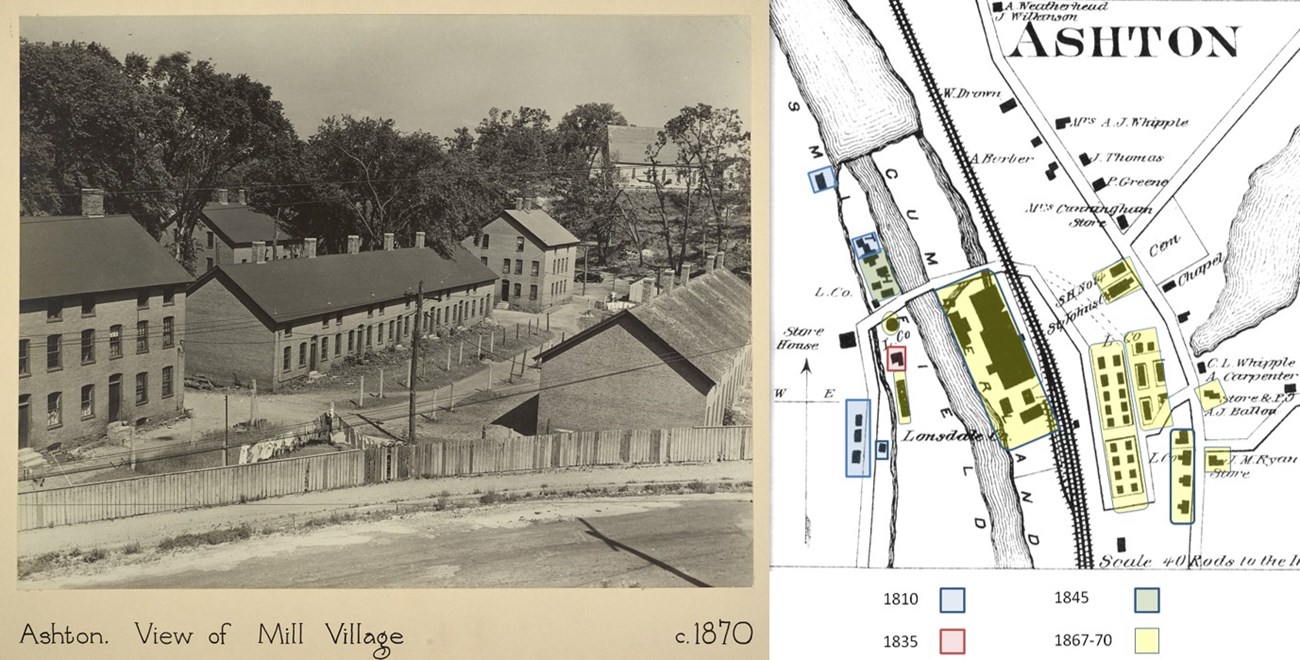

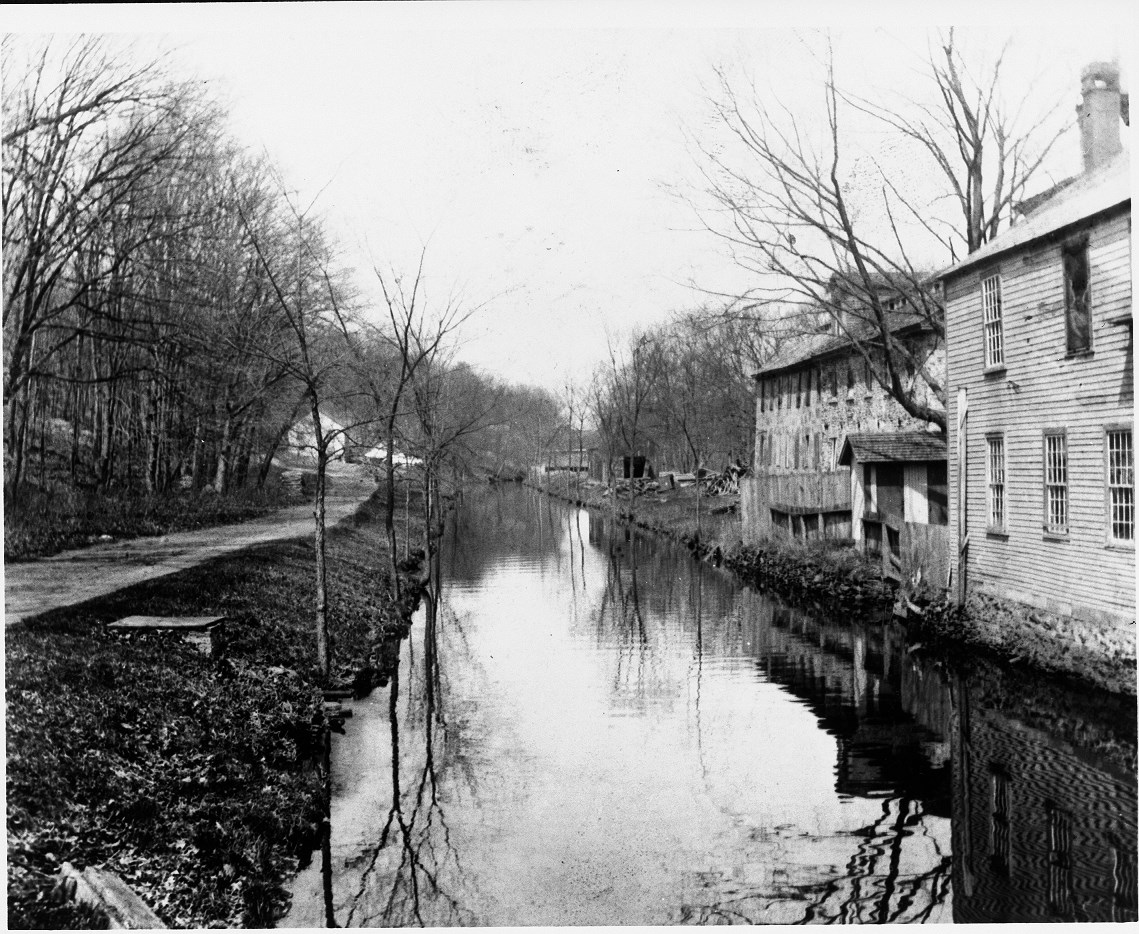

After the War of 1812 ended, however, an economic downturn caused the mill to fail. In December of 1820, census taker Joseph Mann reported that the mill operated 350 spindles and used about 300 pounds of cotton a week. This report suggests that fewer than 12 men, women, and children, including the managers, were working in the mill. In 1823, Wilbur Kelly, a former ship’s captain for Brown and Ives’ China Trade, bought the small mill village for $5,000. Along with the buildings, he purchased the equipment, waterpower, and dam rights. In 1826, Kelly sold “the free right and privilege to make a navigable canal, towing paths, locks, and bridges” through his factory site to the Blackstone Canal Company for a single dollar. Shortly afterward, Kelly sold the mill and small village to the Lonsdale Water Power Company. In return, he received 900 dollars cash, stock holdings in the new company, and a $500 a year position as the company’s head agent. On behalf of the Lonsdale Company, Kelly purchased additional land and water rights along the Blackstone River in Smithfield and Cumberland. In 1828, the Blackstone Canal opened, and Kelly’s Mill became a stop along its route. Passengers on an early voyage described the scene, recalling, “At Kelly’s factory, a remarkably neat establishment directly up on the canal, we were greeted by the smiling faces of scores of neatly dressed females who thronged the windows of the factory. The banks for some distance here are lined with good stone wall, and it is perhaps the prettiest section of the route up to Albion.” In 1835, Kelly built a manager’s house, which is now the Captain Wilbur Kelly Transportation Museum. He also expanded the mill in 1845. In 1848 the canal closed when the Providence and Worcester Railroad opened on the other side of the river. More efficient than the canal, the Providence and Worcester Railroad made the Blackstone Canal outdated. In 1865, the Lonsdale Company chose to expand their operations at Ashton next to the railroad, instead of continuing to expand the Kelly Mill. Along with the large brick mill, the company built dozens of brick worker houses, a church, a school, manager housing, and a store.

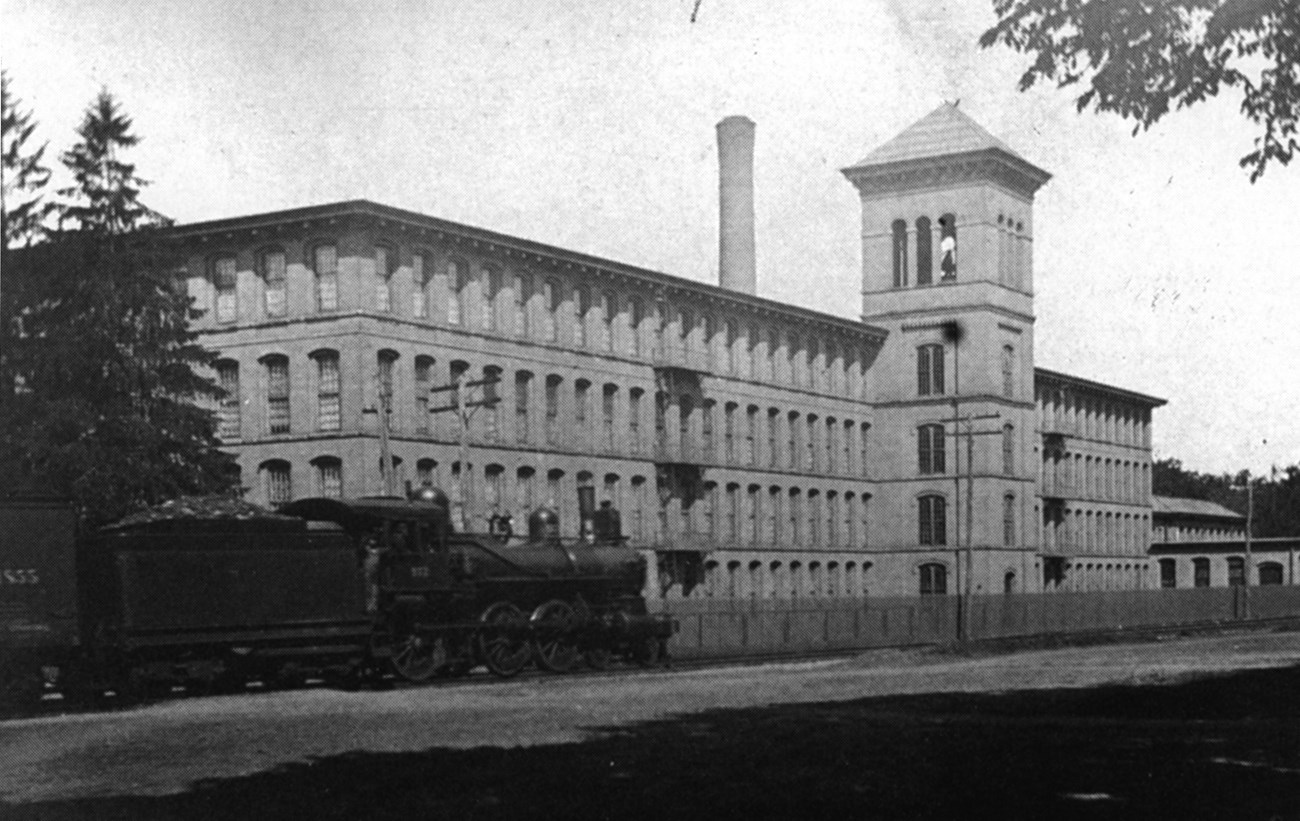

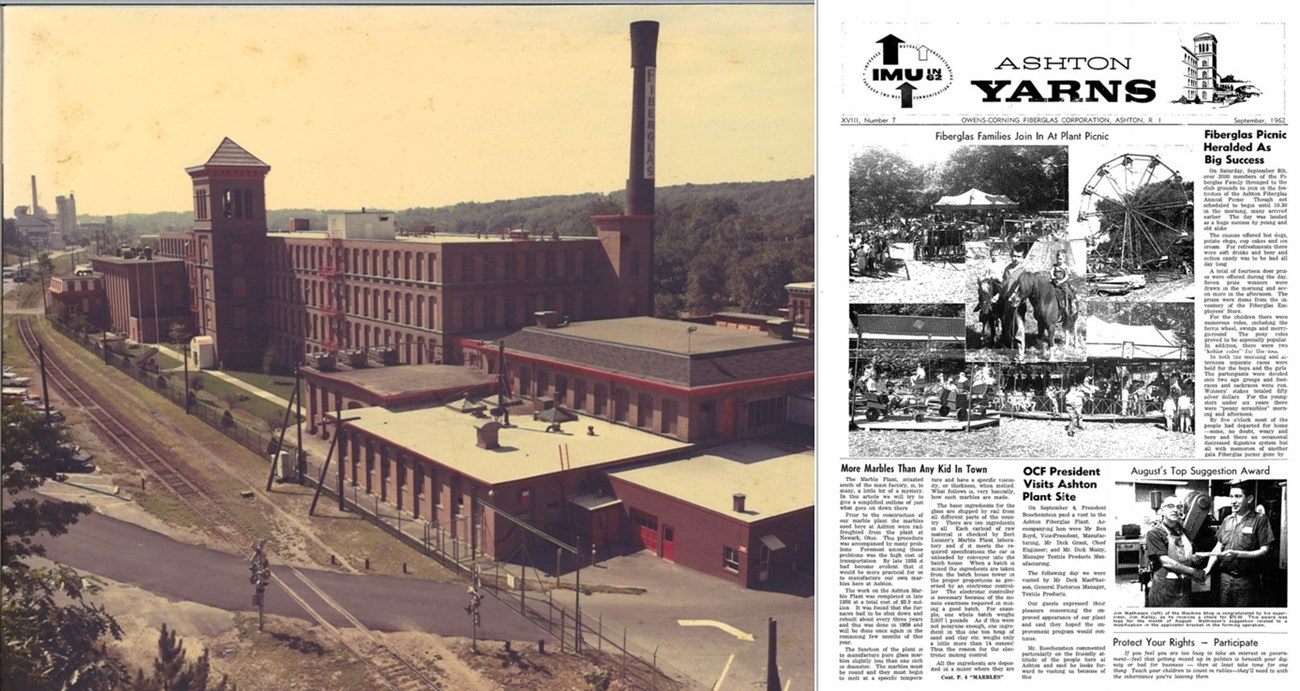

During the 1870s, Ashton Mill was a technological marvel. In 1870, the mill had 700 looms, 38,400 spindles, and 450 employees, and could spin 60,000 miles of yarn in a single day. The mill produced fine muslin cloth, as well as cambric (a lightweight, but fine and dense cotton cloth) and rolled jaconets (a plain, medium weight cotton cloth). Working in Ashton was advertised as an ideal, almost romantic job, particularly for young women. A reporter from a local paper commented in 1870 that “many a vain and idle girl who is tasking her father’s purse for needless finery, and fretting herself because she has nothing to do, and ‘nothing to wear,’ might find it equally beneficial to her health, her spirits, and her purse” to make one herself at Ashton. These girls could earn between $8 and $12 weekly. With this income, "they ought neither be a burden to others, nor spend their time in the frivolities of a semi-fashionable, and wholly foolish and miserable idleness.” By this time, young women and children had been working in Rhode Island and Massachusetts mills for years. Some contemporaries continued to justify their labor by arguing that places such as Ashton offered “healthful” jobs and solutions to social problems. However, mill inspectors found that these mills could often be dangerous places for people to work and some young people would pay a high price while earning these wages. The mill continued to produce cotton cloth until 1936. The Lonsdale Company decided to close the mill due to financial difficulties caused by the Great Depression, as well as the textile industry’s general move to the American South. In 1940, Owens-Corning Fiberglas Company purchased the mill. They used the mill to produce Fiberglas, a type of reinforced plastic that could be woven into cloth. Fiberglas was popular for its flame-resistance. The company made tire cord, drapery, and beta cloth for spacesuits used on the Apollo Moon missions. In 1983, the Owens-Corning Company stopped operating in Ashton.

Today, the Ashton mill has been given a new life as lofts and apartments. The distinct features of the building’s exterior, such as the bell tower and brick construction, are still visible today. The mill village housing is also occupied by families, and the village itself is largely still complete. Ashton remains to this day an excellent example of a Rhode Island System mill village and an image of how American manufacturing grew and evolved through the 19th and 20th centuries. People, Places and Stories

|

Last updated: May 25, 2025