Last updated: January 23, 2025

Article

To the Moon and Back: A Revolution in Transportation

The Transportation Revolution

Transportation. It’s probably something most of us do not think much about. From cars, bikes, planes, and trains, most of us use some form of transportation to travel to work, school, appointments, and whatever else we do in life.

Revolution. A term that can refer to a dramatic social or political change, or simply refer to a cyclical journey.

Put the two together and you are referring to an era that altered the course of human history.

As we commemorate the 250th anniversary of United State independence, we must confront the complex outcomes and changes that continue to evolve from within the American experiment. This requires us to consider the political and social implications of America250 along with the technological and industrial changes wrought since 1776.

The Setting

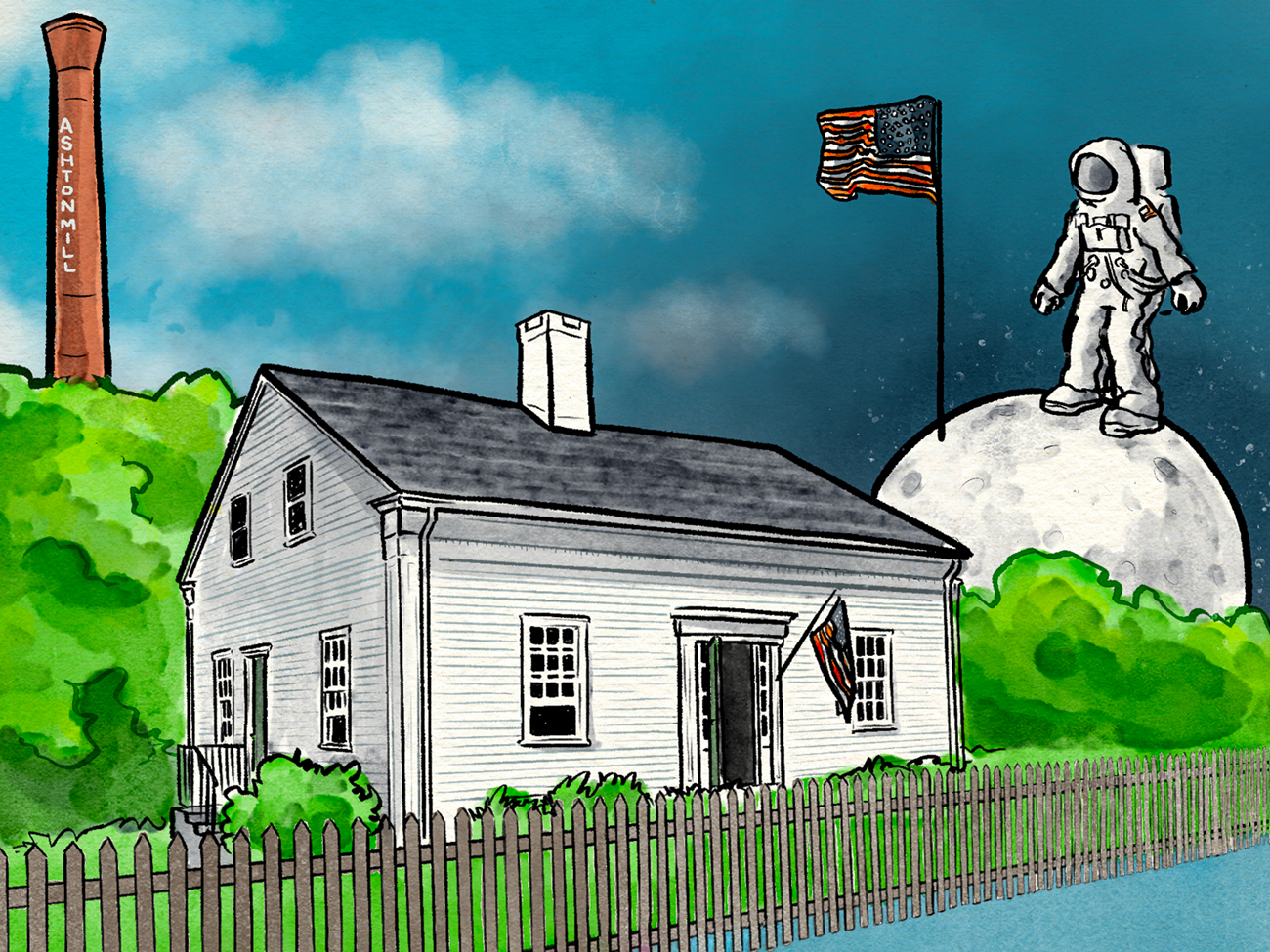

In Blackstone River State Park, there is a small house with a big story inside. It’s the story of the transportation revolution in the United States.

The Captain Wilbur Kelly House Museum of Transportation is located in Lincoln, RI, within one of the six locations that comprise Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park. This solitary and unassuming museum was once the home for the manager of the Kelly Mill complex. Historically, it was part of a booming industrial landscape nestled on the banks of the Blackstone River. Today it sits adjacent to a quiet canal towpath in a state park that preserves approximately eighty acres of green space amid suburban development. With change being the only constant, the Kelly House is a great place to learn about the rise and fall of industry in the Blackstone Valley.

The Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park tells the story of America’s Industrial Revolution. A pivotal part of that larger story is the Transportation Revolution. From the time of the ancients and the invention of the wheel, human beings transported themselves and goods across the landscape in the same way for millennia. Those who lived through the American Revolution generally transported goods in the same way Julius Caesar had moved his Roman Legions across Europe. But the last 250 years have brought accelerated means of transportation and new heights for human achievement. More recent innovation allowed people to leave the atmosphere and travel to the moon.

The people who lived in and around the Kelly House were witnesses to the rise of new technologies and modes of transportation, from the canal to the railroad, to the highway. Some even played a role in ensuring the safety of early astronauts. The events leading up to this dramatic change, or revolution, in transportation were first set into motion thousands of years ago.

Indigenous Peoples and Kittacuck

The name Blackstone comes from the first English colonizer to settle along its banks: the Reverend William Blackstone. But the people who inhabited the river valley for time immemorial referred to the water course by many different names. Some called it Kittacuck; others Pawtucket. The Nipmuc, Narragansett, and Wampanoag peoples were the original inhabitants of this landscape. Our story begins with them about 1,000 years ago.

Due to the frequency of waterfalls and rapids, the Blackstone is not an easily navigable river. It is possible that small sections of the river were used by indigenous people to move up and down the river seasonally. But transportation was far from the most critical use of the river. Fish provided a dietary supplement to farming and hunting, especially in the spring when anadromous fish swim upriver to spawn. Evidence indicates indigenous peoples used weirs or wooden obstructions which functioned as a net to trap fish. These weirs were most effective at narrow and shallow choke points along the river. These locations also served as ideal places to cross the river.

At the far southern end of the park, the Martin Street Bridge crosses the river above a natural ford. Archaeological evidence indicates this place has long been used to cross the river. A second crossing place, located behind the Kelly House and known as Pray’s Wading Place, is another natural point to cross. Although there is less evidence of this location being used, these crossing places were critical parts of Native American trade networks which wove across southern New England.

European Colonization and the American Revolution

As Europeans began settling in the region in the late 17th century, they often established farms and homesteads along riverways and preexisting Native American trade routes. During the colonial period, settlers purchased many of their goods from Great Britain.

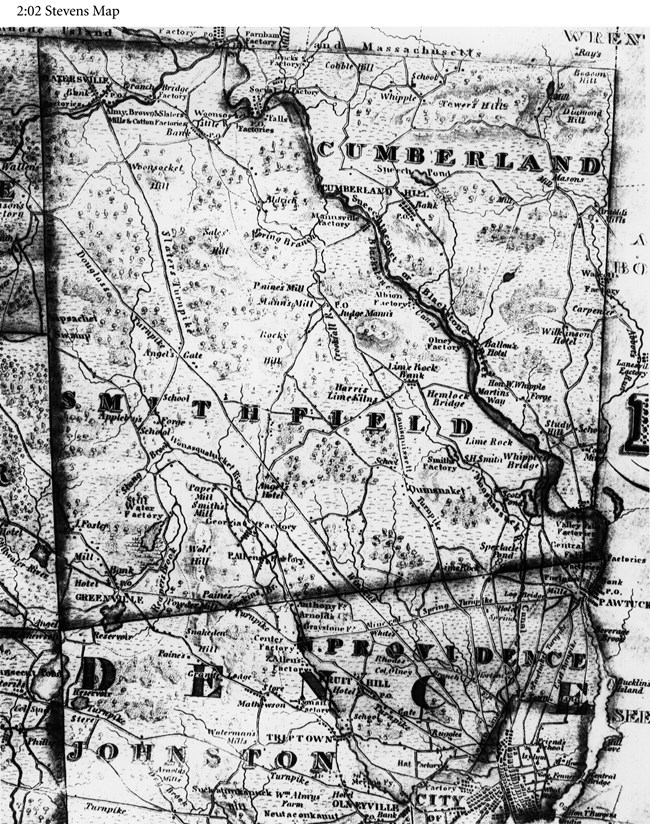

Following Moses Brown and Samuel Slater’s successful experiment in Pawtucket in 1790, citizens in the newly independent United States began to expand industrial enterprise across the valley. During this period of growth, the necessity for better road networks was evident. The Great and Mendon Roads were improved, and a new system of turnpikes including the Louisquissett, Douglass, and Slaters were constructed. These improvements made transportation slightly easier and more efficient.

Many people in the United States continued to purchase goods from Great Britain through the early 1800s, despite fighting a war for independence. That would change during the administration of President Thomas Jefferson. Around the time of the Embargo Act (1807) and the War of 1812, strained relations with Great Britain led to the proliferation of textile mills in the valley. The Smithfield Cotton and Woolen Mill (later known as the Kelly Mill), which was located within the park, is just one of many examples. Several investors pooled money, land, knowledge, and resources to construct the mill around 1815. They built a small village which included workers’ housing and a gristmill. In 1823, a former ship’s captain and burgeoning textile merchant, Wilbur Kelly, purchased the fledgling mill. Kelly would be plagued by much of the same issues the former owners had faced, especially exorbitant prices for transporting raw materials and finished products.

The Blackstone Canal

Along with the construction of new mill and worker homes, industrialists advocated for a transportation canal. This was not a novel idea. Transportation canals had long been used in various parts of the world. In the United States, canals like the Eerie and Middlesex were successful in their early years of operation. This led to a canal building craze which lasted from 1800 to 1850. As early as the 1790s, Providence-based merchants like Moses Brown advocated making the Blackstone navigable by constructing a canal. This would link the headwaters of the river, located in Worcester, MA with Providence, RI. However, Massachusetts politicians feared this would divert critical trade goods away from Boston, MA to Providence. This would be detrimental to Boston’s economy, and as a result, Boston officials blocked the canal idea for three decades.

By 1825, the success of other canals proved the necessity for a Blackstone Canal. Transportation prices were exorbitant. A canal would provide cheaper transportation for business owners. A canal company was formed, about $700,000 was raised through subscriptions, and construction began in 1825. Hundreds of laborers, many Irish immigrants, dug the canal largely by hand with shovels, pickaxes, and wheelbarrows. In a few spots, black powder was necessary to blast through rock. The portion of the canal that runs through the park was completed in 1827. Laborers dug the trench, built up the towpath, and skillfully lined the walls with dry laid stone. This portion of the canal stands as a testament to the skill and hard work of those who built it.

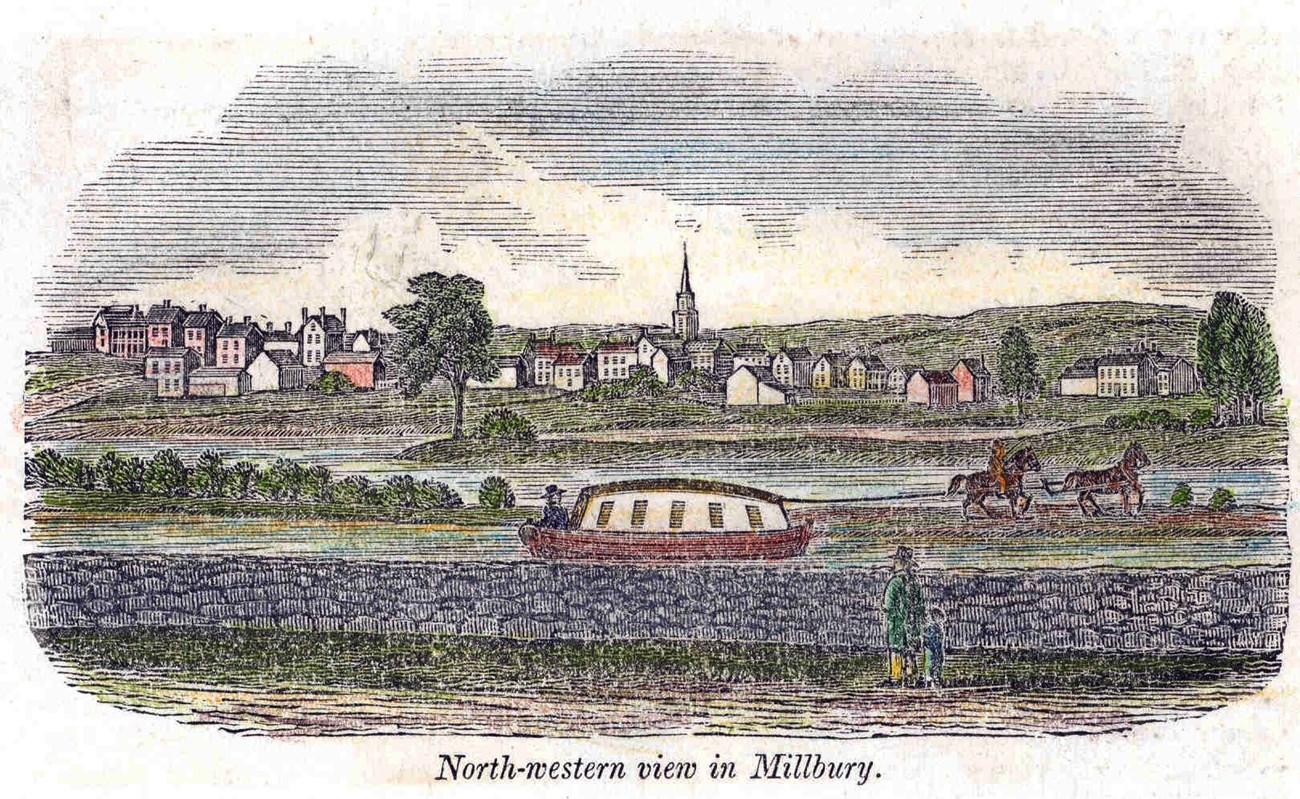

The canal opened for operation in 1828. Two-horse teams walking along the towpath pulled barges the length of the canal. Traveling at about four mile per hour, it would take 2 days to make the 48-mile journey between Worcester and Providence. Contemporary newspaper articles leave a detailed account of the types of materials being transported: foodstuffs, iron, nails, leather products, cotton, paper, brick, scythes, and shoes. These sources also indicate the large number of materials being transported. For example, in April 1830, a total of 1,536 ½ tons were transported on the canal.

Just 20 years later the canal would close in 1848. Although short-lived, the canal provided a means of transportation that was much cheaper than moving the goods by wagon over land. Few could have predicted just how quickly it would be eclipsed by something new. By the 1840s, an iron horse powered by steam would replace the tired horses walking well-worn towpaths.

The Railroad

In the 1830s, railroads began springing up across southern New England. These early trains were not as fast as the ones that would come later, but they could pull more tonnage at a faster and cheaper rate than the barges of the Blackstone Canal. The Boston and Worcester Railroad opened in March 1834. Then the following year, the Boston and Providence Railroad opened. Although both operations hurt the business of the canal company, it was not until the completion of the Providence and Worcester Railroad, opened in 1847, that the canal was finally put out of business.

At a meeting of wealthy industrialists in Worcester a toast was proposed to “The two Unions between Worcester and Providence – The first was weak as water, the last is strong as iron.” The railroad further reduced transportation costs and cut the travel time by more than half. By the mid-1800s, trains could travel between the two cities in a little over an hour, which is about the same time it would take to make the journey by car today. The railroad revolutionized transportation in the Blackstone Valley, providing not only a cheaper means for industrialists to move material, but also a faster way for people to communicate and move across the landscape. Today, the Providence and Worcester Railroad remains an active rail line over 175 years later.

Cruising along the Highway

Although automobiles are commonplace today, they were revolutionary around the turn of the 20th century. The motor vehicles that followed provided another means to transport goods across the landscape. Perhaps even more critical, these automobiles allowed workers to live increasingly further distances from their place of employment. Eventually this would lead to the birth of the suburbs and urban sprawl. But the increase of automobiles also meant that roads intended for horse and carriage were quickly going out of date. The road network that encompasses this site would undergo several eras of improvements.

As part of the New Deal, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration began large-scale investment projects in national infrastructure. The Ashton Viaduct, which casts its shadow over the Kelly House Museum, is just one of many projects originating in that era. Work commenced in 1934, but the project was stalled because of lack of funding resulting from the Great Depression and World War II. The project was completed in 1945. This bridge, a critical part in the opening of Route 116 (George Washington Highway) is just one example of infrastructural improvements made to accommodate the automobile.

Another critical development for automobiles came with President Dwight Eisenhower’s interstate system. General Lucius Clay, head of the interstate planning committee, summed up the need for an interstate system: “It was evident we needed better highways. We needed them for safety, to accommodate more automobiles. We needed them for defense purposes, if that should ever be necessary. And we needed them for the economy. Not just as a public works measure, but for future growth.” The northern edge of the Blackstone River State Park is bounded by Interstate-295 which was constructed in 1969.

MJ Robinson

To the Moon

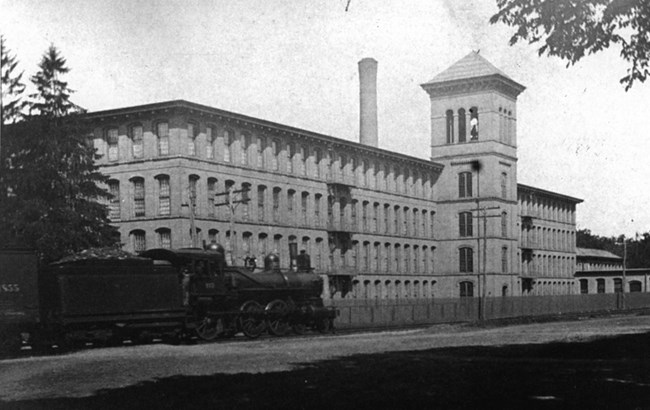

The transportation revolution was not limited to land and water. Just south of the site on the eastern side of the river in Cumberland, Rhode Island, once stood a small municipal airport. Small planes would soar past the large four-story brick Ashton Mill. Some of the people working inside the four walls of that building, perhaps watching those planes soar by, would make something that could allow people to walk on the moon.

Opened in 1869, the Ashton Mill was nearly twelve times the size of the original Kelly Mill. Built to expand operations at Ashton, the mill operated as a textile mill for the next sixty years. In 1941, Owens-Corning Fiberglass purchased the mill, and converted its operation to fiberglass production. The research and design lab was moved to the fourth floor of the mill. Here, scientists began researching and producing a new type of material called beta cloth.

Beta cloth was made of fiberglass and was heat resistant up to 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. This material, which was manufactured in the mill, made up the exterior most layer of the space suits the astronauts wore during the Apollo Missions. The patches for the space suits, also made of beta cloth, were manufactured in the mill. Materials made in this mill touched the surface of the moon.

From a river crossing used for nearly a thousand years to the moon and back, Blackstone River State Park provides numerous examples of the rapid evolution of transportation technology over 200 years.

Visitors today still enjoy many of the fruits of this transportation revolution. We can now travel with more ease and regularity to places 10 to 1,000 miles away from our homes than ever before. People may even soon be able to make regular trips to space! Yet, these advantages also come with their own pitfalls. More automobiles, planes, and trains mean more pollution as these typically are powered by fossil fuels. Carbon emissions is one of the largest contributors to climate change. Most mill workers traveled to their jobs on foot. Commuting to work tends to look quite different (and leave a much bigger environmental footprint) for people in the United States today.

The Kelly House serves as a reminder of a shared past. The question for us today is how we will shape the future. How will our relationship with transportation continue to evolve? What moves you?