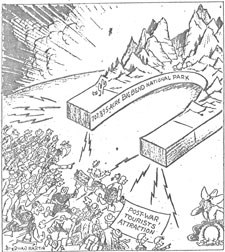

In 1944, American’s attention was focused on distant lands as the Second World War raged around the globe. Despite a world in political turmoil and an uncertain future, it was the year that Big Bend National Park was set aside for public benefit and enjoyment. On theater screens across the country Laurance Olivier was starring in Shakespeare’s "Henry V" and Gene Autry sang "Don’t Fence Me In." It cost merely three cents to mail a first class letter. Scientists at Harvard University construct the first automatic, general-purpose digital computer. DNA is isolated by Oswald Avery. Pensive, a bright chestnut Thoroughbred racehorse, wins the Kentucky Derby. President Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected to an unprecedented fourth term in office. On June 6, American and British troops made their famous D-Day landing on the shores of Normandy, which would turn the tide of the war and change the course of history.

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park What made Big Bend so important that a President would shift his focus from a world in turmoil to the wilderness of southwest Texas? It was a noble purpose. To set something aside for future generations with the fate of the present generation still uncertain was an act of optimism in an uncertain world. Still, for some folks, it was difficult to imagine this wild, rugged country as a park, international or otherwise. For years, most people had viewed it as too remote and dangerous to be of any use. The Spaniards had dubbed the area "El Despoblado," the uninhabited land. While many other areas of the west were being settled at a furious pace, Big Bend’s remote location and harsh terrain dissuaded most aspiring settlers. It was not until after the establishment of nearby military outposts at Fort Davis and Fort Stockton in the 1850s and the coming of the Southern Pacific railroad a generation later, that settlers began to come to the Big Bend in substantial numbers. Many of these early settlers were miners or ranchers.

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park The Big Bend country was a rancher’s dream. Native grasses were abundant and there was adequate water in the form of creeks and springs. Land was cheap and held promise for anyone with the guts and ambition to give it a try. Many place names familiar to park visitors today came from this ranching era: Hannold Draw, Rice Tank, and the Sam Nail and Homer Wilson ranches are but a few examples. Coincidentally, one of the top songs of 1944, "Don’t Fence Me In," seemed particularly applicable to Big Bend ranchers. In the early days, they practiced open range ranching. Only in later years would some of the ranchers find it necessary to fence in their land. Ranching in the Big Bend was not an easy life, but it was home. While the creation of the national park was a popular notion with most Americans, it was not a decision easily accepted by many of the ranchers who were told they would have to sell their land. Under these conditions, many ranchers allowed cattle, sheep, and goat herds to increase in size to the detriment of the grasslands on which they fed. This overgrazing hastened erosion and changed the appearance of desert plant communities. The region was named Big Bend for the drastic change in course of the river from a southeastern to a northeastern flow. As the Rio Grande flows through the Chihuahuan Desert, it carves not only majestic canyons, but also a political boundary. Big Bend’s location on the United States/Mexico border has always provided a mystique to the park. Over the past hundred years, the border has experienced peace and stability as well as raiders and revolutionaries. The Mexican Revolution spilled over the international border several times between 1915 and 1920, resulting in some bandit raids of the area. The most famous of these raids took place at Glenn Spring on May 5, 1916, when several people were killed. However, bandits were only a small part of the story of the border. The majority of folks who lived along the border were neighbors who cooperated in order to survive. In the 1930s, calm returned to the region and the military departed. It was during this time that the wonders of the Big Bend country were becoming known outside the area.

NPS Historic Photograph Collection

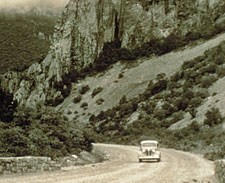

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park Before the area would be suitable for visitors, roads, trails, and facilities needed to be developed. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), an agency born out of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, provided an ideal work force. The CCC was a program designed to alleviate unemployment for thousands of young men while at the same time conserving natural resources. Several hundred young men, most of whom were Hispanic, worked in the Chisos Mountains between 1934 and 1942. Using only picks, shovels, rakes, and a dump truck, the CCC workers surveyed and built the seven-mile access road into the Chisos Mountains Basin. The course of the road and stone culverts have remained basically unchanged over the past seventy years. Later, CCC work crews built the Lost Mine Trail and several stone and adobe cottages in the Basin. It is a lasting tribute to the "CCC boys" that their hard work and skilled labor are still being enjoyed by park visitors today. Despite all the progress made by the creation of the state park and the work of the CCC, Big Bend supporters wanted something more—a national park. They felt that the area was nationally significant and merited recognition as a national park. The National Park Service sent a team to investigate the values of the area. Their report was enthusiastic and they endorsed the national park idea. Unfortunately, two of the team members, Roger Toll of Yellowstone, and George Wright of the Washington office, were killed in a car accident on their return from the meeting. Toll and Wright Mountains were named in their memory.

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park It would take several years and much hard work for the national park to become a reality. In the midst of the Great Depression, park supporters had to come up with the money to purchase all the land within the proposed park area. In 1942, $1.5 million was allocated by the State of Texas to purchase approximately 600,000 acres from private owners. The State of Texas delivered the deed to the Federal Government in September, 1943 and Big Bend National Park was officially established on June 12, 1944. Within a few weeks, the park located its headquarters in the CCC barracks in the Basin. In its first year, Big Bend recorded 1,409 visitors. In recent years annual visitation has increased to over 500,000!

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park The original plans for the national park included a hospital in the Chisos Mountains Basin as well as a large resort hacienda that would have been built by the CCC if World War II had not occurred. There was also a plan for a two-hundred thousand acre longhorn cattle ranch to be located within the proposed Big Bend National Park. The construction of a cog railroad from the Chisos Basin to the South Rim was also considered. Although some of these plans never became reality, Big Bend did become a national park. Unforseen designations have also brought Big Bend international attention. In 1976, Big Bend was recognized by the United Nations as an "International Biosphere Reserve." This designation identifies Big Bend as a prominent example of the Chihuahuan Desert ecosystem and holds opportunities for biological research and environmental monitoring. As the increase in visitation over the past sixty years testifies, more and more people are discovering the pleasures of a visit to one of the most inspiring and diverse parks in the country. Big Bend is a place to relax, to contemplate the pace of the natural world, to challenge one's own outdoor skills, to study wildlife or plants, and to simply enjoy the splendor of wilderness. Big Bend is a gift from those who came before us, who worked hard to promote and protect the area as a national park. Today, we have the opportunity to enjoy and learn from the park as well as the responsibility to protect Big Bend for future generations.

For Further Reading

|

Last updated: December 5, 2022