Last updated: September 17, 2024

Article

Homestead National Historical Park's Landscape

NPS

NPS / M. Tack

Landscape Description

The homestead’s T-shaped configuration results from the arrangement of four 40-acre square plots of land. The landscape is located about five miles west of Beatrice, Nebraska and roughly 50 miles to the south of Lincoln. State Highway 4 roughly delineates the northern border and crosses Cub Creek, which runs through the northern and western areas of the site.

NPS / M. Tack

Two principle native vegetation communities exist at the site: the upland prairie and riparian woodland. The National Park Service manages the tallgrass prairie as part of its efforts to restore the landscape to its conditions shortly after Freeman’s initial settlement. The restored prairie -- one of the oldest in the National Park Service -- contains species such as big and little bluestem, indiangrass, switchgrass, goldenrod, fieldpussytoes, and leadplant.

The other vegetation community, the riparian woodland, also includes a number of native species including bur oak, silver maple, boxelder, red elm, hackberry, and cottonwood. The presence of the woodlands and the creek allude to the site’s historic appeal for homesteading. Cub Creek was a valuable water source in a region prone to prolonged dry spells. The trees provided Freeman an important source of building material and fuel. Freeman also used trees, such as those of the Osage orange hedgerow, to mark property boundaries. The thorns of the Osage orange also made it an effective barrier to contain or exclude livestock. Until superseded by the advent of barbed wire, Osage orange hedgerows were common on homesteads of the Great Plains.

Other historically significantly features within the park include the Daughters of the Revolution monument and a small grave site. The Daniel and Agnes Freeman gravesites, located on the east upland ridge, consist of two footstones and a granite marker. A modern element in the prairie is a raised viewing platform used for interpretation programs.

Landscape History

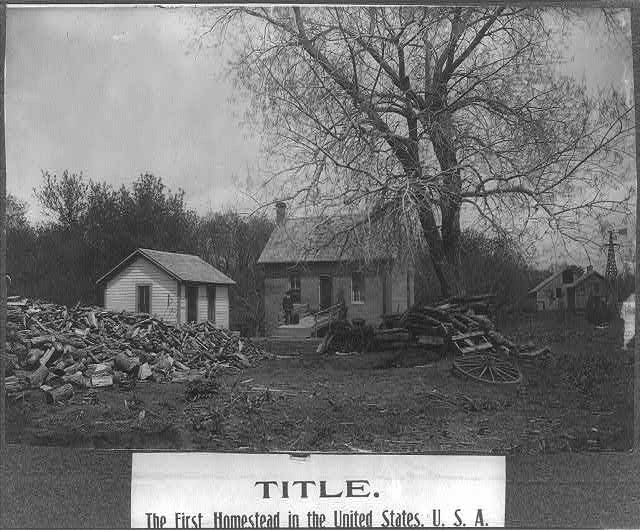

Library of Congress

However, many, like Freeman and his family, found success. After furnishing the site with a log cabin in 1867, he went on to add a two-story brick home, barnyard, feeder barn, granary, corncrib, windmill, and well. The final federal patent was granted in 1869. Daniel, and his wife, Agnes, lived on the homestead until his death in 1908.

Homestead Act of 1862

Teaching with Documents from the National Archives

The Homestead Act remained active for 124 years until its repeal by the 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act. By the early 20th century, the disbursement of 270 million acres or 10 percent of total US land occurred under the Homestead Act. Most homesteaders claimed land in Montana, North Dakota, Colorado, and Nebraska (lands of the Oregon Territory had already been homesteaded through the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850). In totality, approximately 40 percent of homesteaders fulfilled the five year term and made improvements to gain title to their land.

The Homestead Act had a vast impact upon indigenous people. As settlers arrived, Native Americans were displaced and pushed farther west. Many Native Americans died in battles over land or by starvation and diseases brought by the settlers. For many cultures, practices and traditions were almost lost. By 1887, many Native Americans had been relocated to Indian reservations, often far from their traditional lands.

Quick Facts

- Type of Landscape: Historic Vernacular Landscape

- National Register Level of Significance: National

- National Register Criteria: A, B, D

- Period of Significance: 1862-1936