Part of a series of articles titled Disability History: An Overview.

Article

Disability History: The Disability Rights Movement

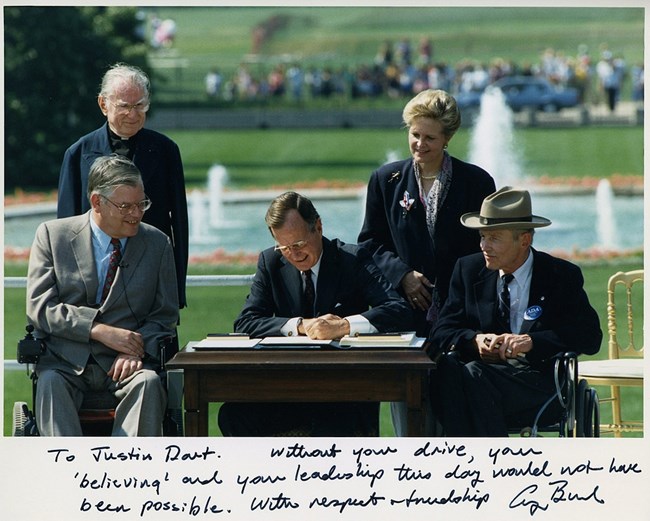

Image from the National Museum of American History (CC BY-SA 2.0; https://www.flickr.com/photos/nationalmuseumofamericanhistory/20825041956/)

Treatment and perceptions of disability have undergone transformation since the 1900s. This has happened largely because people with disabilities have demanded and created those changes. Like other civil rights movements, the disability rights movement has a long history. Examples of activism can be found among various disability groups dating back to the 1800s. Many events, laws, and people have shaped this development. To date, the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the subsequent ADA Amendments Act (2008) are the movement’s greatest legal achievements. The ADA is a major civil rights law that prohibits discrimination of people with disabilities in many aspects of public life. The disability rights movement continues to work hard for equal rights.

Organizations by and for people with disabilities have existed since the 1800s. However, they exploded in popularity in the 1900s. The League of the Physically Handicapped organized in the 1930s, fighting for employment during the Great Depression. In the 1940s a group of psychiatric patients came together to form We Are Not Alone.[2] They supported patients in the transition from hospital to community. In 1950, several local groups came together and formed the National Association for Retarded Children (NARC). By 1960, NARC had tens of thousands of members, most of whom were parents. They were dedicated to finding alternative forms of care and education for their children.[3] Meanwhile, people with disabilities received assistance through the leadership of various presidents in the 1900s. President Truman formed the National Institute of Mental Health in 1948. Between the years 1960 and 1963, President Kennedy organized several planning committees to treat and research disability.[3]

The US Congress has passed many laws that support disability rights either directly or by recognizing and enforcing civil rights. Civil rights laws such as Brown v. Board of Education and its decision that school segregation is unconstitutional laid the groundwork for recognizing the rights of people with disabilities. Several sections of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which specifically address disability discrimination, are especially important to the disability rights movement. Section 501 supports people with disabilities in the federal workplace and in any organization receiving federal tax dollars. Section 503 requires affirmative action, which supports employment and education for members of traditionally disadvantaged minority groups. Section 504 prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in the workplace and in their programs and activities. Section 508 guarantees equal or comparable access to technological information and data for people with disabilities. The regulations for Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 were written but not implemented. In 1977, the disability rights community was tired of waiting, and demanded that President Carter sign the regulations. Instead, a task force was appointed to review them. Afraid that the review would weaken the protections of the Act, the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD) insisted they be enacted as written by 5 April 1977, or the coalition would take action. When the date arrived and the regulations remained unsigned, people across the country protested by sitting-in at federal offices of Health, Education, and Welfare (the agency responsible for the review). In San Francisco, the sit-in at the Federal Building lasted until April 28, when the regulations were finally signed, unchanged. This was, according to organizer Kitty Cone, the first time that “disability really was looked at as an issue of civil rights rather than an issue of charity and rehabilitation at best, pity at worst.”[4]

The 1975 Education of All Handicapped Children Act guaranteed children with disabilities the right to public school education. These laws have occurred largely due to the concerted efforts of disability activists protesting for their rights and working with federal government. In all, the United States Congress passed more than 50 pieces of legislation between the 1960s and the passage of the ADA in 1990.

Self-advocacy groups have also shaped the national conversation around disability. Self-advocacy means representing one's own interests. Such groups include DREDF (Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund), ADAPT (Americans Disabled for Accessible Public Transportation, later changed to Americans Disabled Attendant Programs Today), and the CIL (Center for Independent Living). The CIL provides services for people with disabilities in the community. The CIL began in the early 1960s at Cowell Memorial Hospital. Located in California, Cowell Memorial Hospital was once listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The building is now demolished, but its legacy remains. The hospital supported the "Rolling Quads" and the "Disabled Students Program” at University of California Berkeley. Students Ed Roberts and John Hessler founded both organizations. Both men lived with physical disabilities and needed to find housing options after their acceptance to the university. University dormitories could not manage Roberts' iron lung, an assistive breathing device for people with polio, or Hessler's physical needs. Hessler and Roberts instead lived at Cowell Memorial Hospital when they arrived at college in the early 1960s. With the assistance of College of San Mateo counselor Jean Wirth, they demanded access to the school and encouraged other students with physical disabilities to attend UC Berkeley. They also influenced school architecture and planning. UC Berkeley eventually created housing accommodations for these students. It was there that the students planted the seed of the independent living movement. The independent living movement supports the idea that people with disabilities can make their own decisions about living, working, and interacting with the surrounding community. This movement is a reaction to centuries of assisted living, psychiatric hospitals, and doctors and parents who had made decisions for individuals with disabilities.

Roberts, Hessler, Wirth and others established the Disabled Students Program at UC Berkeley. Although this was not the first program of its kind-- Illinois offered similar services beginning in the 1940s-- the UC Berkeley Program was groundbreaking. They promoted inclusion for all kinds of students on campus. The program inspired universities across the country to create similar organizations. Many of these organizations are still active today.

Photo by David (CC BY-2.0; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Frank_Kameny_June_2010_Pride_1.jpg)

The Rolling Quads and CIL are among two groups from the disability rights movement. Disability activists also work with other communities to attain their goals. People form communities based on shared values, ideas, and identity. The strength and activism of a community can help change attitudes across society at large. Perceptions of disability and resulting treatment often intersect with other groups advocating for their civil and human rights. One example of this change is the treatment of the the gay and lesbian community. Doctors regarded homosexuality as a disease well into the 20th century. They could send men and women to psychiatric hospitals for their sexual preference. It was not until the 1970s that this "diagnosis" changed.

The Dr. Franklin Kameny Residence is part of this important history. Kameny had served as an astronomer and worked with the U.S. Army Map Service. In the 1950s, he refused to reveal his sexual orientation to the government. In response, the US government fired Kameny from his job. Kameny spent the rest of his life working as an activist and advocate for LGB rights. His home provided the space for people to safely express and identify themselves. In 1973, Kameny successfully led the fight to abolish homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The DSM is the official handbook used by healthcare professionals to diagnose psychiatric issues and disabilities. This decision legally removed the status of homosexuality as a disorder. It also helped shift perceptions of homosexuality. More and more people began to understand it was not wrong or defective. The Kameny Residence continues to help us recognize and embrace the work of the gay civil rights community.

Other activists also took to the streets and demonstrated for disability rights. Some of these protests occurred at locations that are today listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1988, students at Gallaudet University, the only American university specifically for deaf students, led the "Deaf President Now" protest. Students made several demands, calling for a Deaf president and majority Deaf population on the Board of Trustees. This week-long protest resulted successfully in the appointment of deaf president, Dr. I. King Jordan. Their protest inspired inclusion and integration across communities.

Two years later in 1990, protesters gathered on the steps of the United States Capitol building. They were anxiously awaiting the passage of the ADA, which had stalled due to issues around transportation. Public transit companies fought against the strict regulations for accessibility, and their lobbying efforts slowed the entire process. In response, a group of individuals with disabilities headed for the Capitol. They tossed aside their wheelchairs, walkers, and crutches and ascended the steps. This event has since become known as the "Capitol Crawl." By dragging themselves up the stairs, these protesters expressed their daily struggles due to physical barriers. In so doing, they highlighted the need for accessibility. Iconic images of this event spread across the country. The Americans with Disabilities Act ultimately passed in July of 1990 and was signed by President George H.W. Bush. The ADA and other civil rights legislation have transformed opportunities for people with disabilities. However, over 25 years later, there is still much work to be done.

Article by Perri Meldon.

This article is part of the Telling All Americans’ Stories Disability History Series. The series focuses on telling selected stories through historic places. It offers a glimpse into the rich and varied history of Americans with disabilities.

References:

[1] Disability Minnesota. The ADA Legacy Project: A Magna Carta and the Ides of March to the ADA, 2015

[2] Disability History. Disability Militancy - the 1930s; Fountain House. The Origin of Fountain House.

[3] Michael Rembis, “Introduction,” in Michael Rembis, ed. Disabling Domesticity (Palgrave Macmillen).

[4] Grim, Andrew. “Sitting-in for disability rights: The Section 504 protests of the 1970s.” O Say Can You See? Stories from the National Museum of American History, July 8, 2015.

[5] Disability History. Disability Militancy - the 1930s; Fountain House. The Origin of Fountain House.